As readers of this blog are well aware, at the beginning of the year, the ICC Court announced that it would start to publish the names of arbitrators serving in ICC administered cases. Michael McIlwrath has commented on this policy on this blog.

When the first six names and the corresponding information were released in June 2016, the snapshot of arbitrator appointment at the time was surprisingly young, and surprisingly female: At that point in time, six sole arbitrators had been appointed, three of them were women. Looking at the biographies on the website of the arbitrators, the majority – both male and female – of them struck me as young (at least by the standards of the arbitration community, and using graduation and bar admittance dates as proxies for age). It certainly was not a result I had expected. On the other hand, it was hardly a surprise that the first cases all featured sole arbitrators. Almost by definition, the appointment process must be faster than in the case of a three member tribunal.

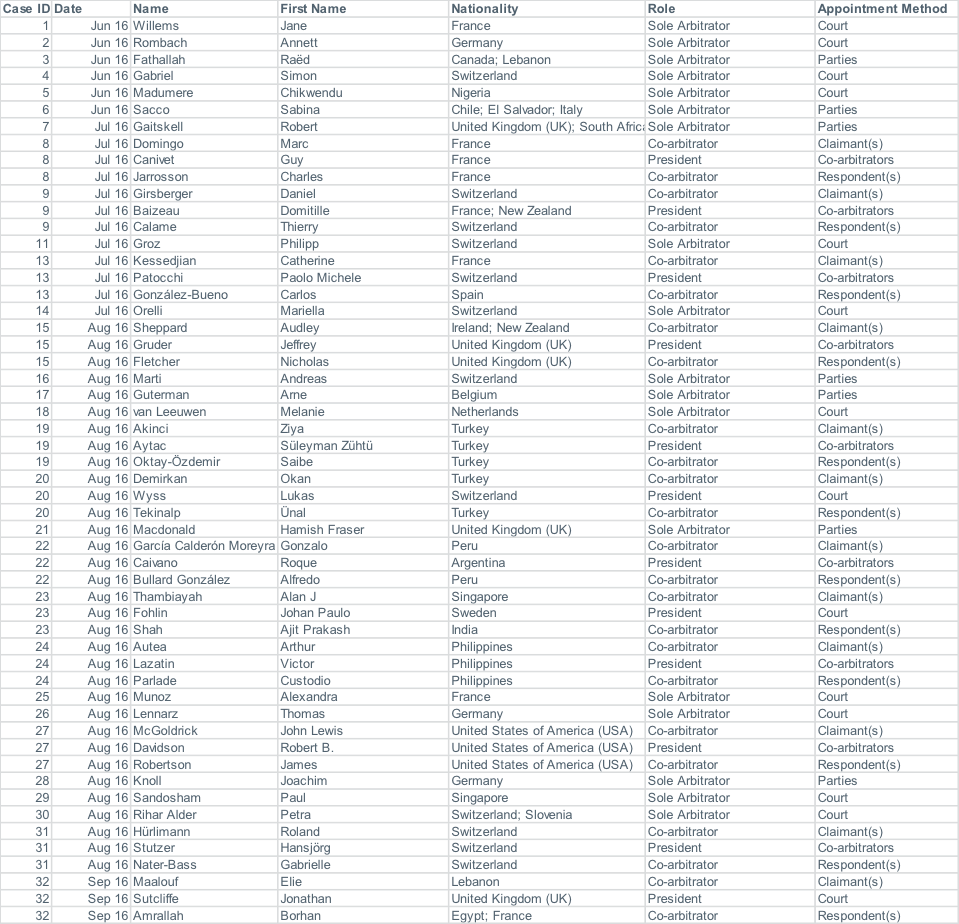

From a statistical point of view, that first set of cases clearly was not a robust representation of any trends. I rather arbitrarily decided to do some number crunching, once the threshold of 50 arbitrators has been exceeded. This is now the case: As of today, data is available for 54 arbitrators (see below). That total is composed of 18 sole arbitrators and 12 tribunals of three arbitrators, so the sample represents 30 cases in total. Over the last three years, the ICC has had, on average, 786 requests for arbitration per year. Our sample of 30 cases would thus represent about 4% of the ICC’s annual case load.*

Appointment Method

Let us first look at the appointment methods: Of the 18 sole arbitrators, the ICC Court has appointed 11 (61%), whereas seven sole arbitrators (39%) were appointed by the parties. The tribunals comprise 24 co-arbitrators, all of whom were appointed by the parties, and 12 presidents. Of those, the majority, namely nine (75%), there appointed by the co-arbitrators, and three (25%) were appointed by the ICC Court. If one looks at the overall number of appointments, then 14 arbitrators (26%) out of the 54 were appointed by the court, and the others by the party-appointed arbitrators or the parties themselves. So far, no arbitrator has been appointed more than once.

Nationality of Arbitrators

No surprises here: The Swiss arbitration community has a solid lead. 12 of the 54 arbitrators hail from Switzerland (22%). Swiss lawyers preside over three (25%) of the 12 tribunals. The ICC court has made 14 appointments in total. Out of these 14 appointments, four (29%) went to Switzerland, namely one out of three presidents (33%), and three out of 11 sole arbitrators (27%).The second most popular nationality is French. La Grande Nation provides eight arbitrators (15%), followed by Turkey and the UK each with five arbitrators (9%). However, as I will discuss in more detail below, looking at the nationality alone may not give the full picture – and Switzerland’s position could be even stronger than it appears on that criterion alone.

International Diversity of Tribunals

I also looked at the international diversity of the tribunals. In the three cases in which the ICC Court appointed the arbitrator, the president comes from a different jurisdiction than his (all of the court appointed presidents were men) co-arbitrators. The outcome is markedly different in the nine cases where the president was appointed by the co-arbitrators: only in two cases (22%) did the co-arbitrators choose a president from a different jurisdiction. The other seven tribunals are homogeneous from a jurisdiction point of view.

A brief note on methodology: The ICC table stated the nationality of the arbitrators, but not the jurisdiction(s) in which they are qualified. Seen from a nationality point of view, the tribunals look more diverse then they, in my opinion, really are. The New Zealander, for example, who was appointed president in Case 9, is a partner in a Swiss law firm and admitted to the Geneva bar. Her compatriot in Case 15 is a partner in an English law firm and admitted as a solicitor in England and Wales. Therefore, the tribunals in cases 9 and 15 are comprised of arbitrators from the same jurisdiction – in passing, this finding also confirms that New Zealanders are amongst the most international and outgoing jurisdictions. The arbitrators of non-Swiss nationality in cases 6 and 28 also practice in Swiss law firms. If I include the three non-Swiss arbitrators practicing in Swiss firms into the Helvetic contingent, the Swiss share goes up from 22% to 28%. Other jurisdictions, such as France, would also benefit from such adjustments, with the non-French arbitrators in cases 3 and 18 being partners in Paris law firms, causing the French share to increase from 15% to 19%. On the other hand, the Middle East would feature more strongly under an alternative method, as arbitrators in the sample are based in Dubai and Abu Dhabi, but the UAE do not show up in the nationality column.

It would be my suggestion to the ICC to list not only the nationalities of arbitrators, but also the offices from which they practice and the jurisdictions in which the arbitrators are qualified. These appear to be better proxies for where these arbitrators have their, to borrow a phrase from our insolvency friends, “main centre of interest”, rather than nationality alone.

The three presidents appointed by the ICC Court hail from the UK, Switzerland and Sweden. The Swede appointed president in Case 23, however, has spent most of his professional career in Hong Kong. Hence he appears to a better fit for a tribunal with an Indian and Singaporean co-arbitrator than his nationality alone would indicate. As already mentioned, four of the 11 sole arbitrator appointments by the Court went to Switzerland. Two appointments each went to France and Germany, with the remaining ones going to the Netherlands, Nigeria and Singapore.

Arbitrator Background

In order to assess the professional backgrounds of the arbitrators, I ran Google searches against the names published by the ICC. I found biographies, mainly on their law firm’s websites, for the vast majority of arbitrators. On that basis, I feel reasonably certain that the person I found is actually the arbitrator listed. However, with some names more common than others, some degree of uncertainty remains. **

This having been said, most arbitrators are in private practice, namely 78% in my assessment. The law firms in which they practice represent the entire spectrum of international business law firms, from global firms such as Baker McKenzie and Clifford Chance to arbitration-focused firms such as Levy Kaufmann-Kohler or Derains & Gharavi. No big surprises here. The appointments are well spread out. In our sample, only three firms field two arbitrators. Not surprisingly, two of them are Swiss firms, namely Homburger, with two female partners serving as arbitrators, and Lalive, with woman and a man having been appointed. The third firm is Clifford Chance, with two arbitrators out of London and Singapore.

All of the UK lawyers in the sample are English qualified. Including one English qualified solicitor of New Zealand nationality, my analysis shows five English qualified lawyers. Three are barristers, all of them QCs. One of the solicitors also is a QC, so silks dominate the English contingent with four out of five appointments (80%).

The remaining arbitrators either hold academic positions (9%) or are (retired) members of the judiciary (9%). The arbitrators from academia exclusively come from civil law jurisdictions. Finally, there are two non-lawyer arbitrators, a civil engineer and a business person, making up the remaining 4%.

Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex (But Only Now Are Able To Ask)

Last, but by no means least, I turn to the issue of gender. I did not expect the June 2016 number of 50% female arbitrators in the larger sample, and was curious where this number would come out in the longer run. In our sample of 54 arbitrators, 11 women (20%) have been appointed.

As already mentioned above, all of the presidents appointed by the ICC court were men. The picture is markedly different for sole arbitrators. Six out of the 11 sole arbitrators (55%) appointed by the ICC Court are women. Of the 12 tribunals, eight are all male (67%). In the other four tribunals, the woman arbitrator serves as co arbitrator in three and as president, appointed by her male co-arbitrators, in one case.

Looking at total appointments, the ICC Court went for women in 6 out of 14 cases, that is, in 43% of its appointments. This is way above the ratio of the other appointments: Between them, the parties and co-arbitrators appointed five female arbitrators, from a total of 40 appointments, or in 12.5% of these cases. So from the data, it appears to be clear that the ICC Court as an institution promotes the appointment of women as arbitrators.

Conclusion

First, I would like to applaud the ICC for the transparency it has created. It would be good if other institutions were to follow. Other than that, I believe that readers of this blog will have their own ideas, judgements and prejudices on arbitrator appointments in general and institutional policies in particular. It would be nice to hear from you what your reactions are! Ideally, this data will dispel some myths about appointment practices. And the more data becomes available, the more precise the picture will get, allowing us to see trends and patterns – as well as changes of such patterns.

***

The Sample Data

The chart published by the ICC on its website lists all arbitrators in ICC Arbitration cases registered since January 1, 2016. The data is published once the Terms of Reference have been established. The chart is updated monthly. The Case ID is for publication purposes only and does not reflect the actual ICC case number. Arbitrators with the same Case ID belong to the same arbitral tribunal. The table below represents the publication on the ICC website as of September 9, 2016. ***

* Not all requests for arbitration proceed to the stage where Terms of Reference are agreed, and that is the point at which the ICC data is releases. Thus, my point of reference is not an exact match, and the sample may represent more than 4%, but the number of requests for arbitration is the best representation of the overall case load that I have available for these purposes.

** For example there are, believe it or not, two Swiss attorneys by the name of Lukas Wyss. But since they are both partners in major Swiss law firms, the ambiguity did not impact the analysis. I had to exercise some judgement in allocating arbitrators to one of the categories. For example, I counted arbitrators as being in private practice, if the information on the web created the impression that their academic appointments were ancillary to their work as attorneys.

*** I have omitted the columns on arbitrator and case status from the ICC table (all were active) to improve readability and have corrected some minor errors (confusion of first and family names in cases 18 and 24).

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.