If James Bond practiced law, it would be international arbitration. Don’t believe me? Just consider how many international arbitration cases could be great plots for a James Bond movie.

Take, for example, the case in which an Israeli investor was arrested in Tbilisi and jailed following a cognac-laced sting operation that caught the investor on tape—recorded by a camera hidden in a plant in a lavish hotel room in Istanbul—agreeing to pay millions in bribes to a Georgian foreign minister. In another case, documents meant For Your Eyes Only were hacked from the Kazakhstan government’s computer network and introduced as evidence against Kazakhstan.

Meanwhile, it may be that Diamonds Are Forever, but diamond mining concessions apparently are not, at least if you are Swissbourgh Diamond and the mines are in the Kingdom of Lesotho. Hugo Chavez thought he had a Goldfinger in nationalizing Venezuelan natural resources, but instead he was buying his country a slew of investment arbitration claims, including most recently a $1.2 billion award for nationalization of a gold mine. In another case, Laos initiated criminal investigations for alleged bribery by American investors who sought to develop a local Casino Royale.

Finally, in a plot stranger than any 007 fiction, an Israeli investor found out the hard way that The Spy Who Loved Me can be a dangerous double-agent. That case brought together a buccaneering tycoon investor with a lavish Italian yacht, an aging (now deceased) Guinean dictator, his youngest and most beautiful of four wives, the biggest iron-ore resources on the planet located in one of the poorest countries on the planet, the FBI and a wiretapping sting operation, philanthropist George Soros, a French businessman, armies of lawyers, several Swiss investigators, racketeering charges in New York, a McMansion in Florida, and allegations of South African agents financing an African election manipulation.

I could go on. But you get the point.

Out of all this cinema-ready drama, there are two essential points.

First, these cases illustrate how international arbitration is consistently being entrusted to resolve many of the world’s most important disputes. In addition to questions about antitrust law or the price of natural gas for Europe, with increasing frequency, international arbitrations involve criminal intrigue promiscuously intertwined with the arbitral proceedings themselves.

As a consequence, arbitrators today are being asked to engage directly with corollary criminal investigations or proceedings—by ordering suspension of criminal prosecutions by State parties, by investigating allegations of criminal misconduct, by taking (or refusing to take) evidentiary account of them, or by referring potential criminal conduct for police action. Although taken for granted on a case-by-case basis, the importance of this trend should not be underestimated. How and how well international arbitration handles allegations regarding illicit and unlawful conduct has critical importance for the future of international arbitration, which brings me to my second point.

In every 007 movie, we know from the start of opening credits that Bond will overcome the most extreme odds. And we never doubt that Bond is on the side of good, battling for nothing less than the safety of the world.

Similarly, we regard international arbitration in exclusively heroic terms—we use the term “pro-arbitration” as a euphemism for international law and order, and as means to advance the best aspects of international trade, multi-culturalism, and global governance.

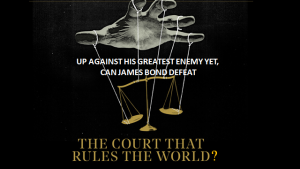

But we don’t get to script how the rest of the world sees international arbitration. Check out what might be the poster for a new James Bond film:

Actually, this isn’t a movie poster at all. It is the slightly-modified cover image for an article—one of several—attacking the legitimacy of international arbitration. In this piece, international arbitration is not the hero in a story about law and justice triumphing over chaos in the world. International arbitration is instead a dark villain, a judicial overlord that aims at subverting democracy and the common good in favor of mustache-twirling corporate conglomerates and their villainous financiers. And international arbitration seems increasingly to be type-cast in that role, not only by progressive media outlets, but also by such stalwarts as The Economist. It is fair to say that a Spectre is hanging over international arbitration.

Meanwhile, like a Thunderball barreling downhill, criticisms of international arbitration are also gaining speed and momentum in the political mainstream in Europe, Latin America, and now the United States. As these public attacks become more vociferous, they should Scare the Living Daylights out of us.

While the most public attacks take aim at investment arbitration, the critiques don’t stop there. Last Spring, Lord Chief Justice John Thomas, probably the most authoritative jurist in England and Wales, made an impassioned plea that international arbitration was undermining the development of the common law and that courts need a more active role in commercial disputes.

Other criticisms are coming from within the system. Users complain about costs, delay, and—echoing some outsiders’ complaints—lack of transparency and accountability. Meanwhile, new parties from parts of the globe not historically active in the field express concerns that international arbitration seems to have an inherent bias that favors North American and European legal cultures, that the pool of international arbitrators is not diverse enough to reflect the range of participants and interests, and that the arbitrator selection-process provides unfair advantages for “repeat players” and entrenches the existing cartel.

Taken together, the range of general complaints can be distilled into a relatively limited set of specific concerns: insufficient oversight, lack of accountability among an overly concentrated core group of players, and the absence of meaningful and binding ethical norms, particularly for the arbitrators.

Unrivaled by any viable alternatives, international arbitration had historically rested on a dismissive Live and Let Die approach to such concerns. With increasing support for mediation or forum selection clauses as potentially viable alternatives, however, we should be shaken, not stirred, into action.

What do these critiques mean for all of us who work in international arbitration? It does not require a Goldeneye to see the answer. It merely requires that, as we tend to the needs of our clients, our organizations, our institutions, and our own professional goals, we also look beyond the most immediate, short-term self-interests to see how our individual actions affect the system, and hence our own long-term enlightened self-interest. It does not do anyone—attorney, client, arbitrator, outside funder, or institution—any good to have their case become the poster child for some endemic problem or controversy in international arbitration. When one actor in a particular setting does not have the wherewithal to see or act beyond immediate strategic considerations, others should be inspired by longer-term self-interest to step in.

Let me make this general exaltation a little more concrete with specific examples.

From Russia With Love, we got the Yukos case. It is the biggest award in the history of international arbitration, but the case is perhaps best known for bringing the cameras in for a close-up on the issue of the use and alleged abuse of the role of a tribunal secretary.

While external hindsight is always easier, for those of us in the audience, it still seems difficult to understand how every single one of the numerous individuals involved in representation or management of the case failed to foresee the problems with what has been characterized as tribunal secretary excess. Some foresight and modest intervention seemingly could have avoided the worst of the resulting headlines.

Even if that foresight was elusive in the Yukos proceedings, the case has been impetus for important dialogue and reforms, most notably in the Young ICCA undertook to draft a Guide on Arbitral Secretaries. This Guide, and others like it, demonstrate the ability of the international arbitration community to respond constructively to problems that arise in specific cases, but have broader consequences.

The HEP v. Slovenia case is another example. There, one side apparently decided to introduce new counsel from the same chambers as the presiding arbitrator shortly before the first hearing. But, according to the tribunal, that side refused to disclose details or cooperate in response to inquiries about the new attorney. While the parties and counsel were not setting out to become a test case, HEP v. Slovenia now represents a watershed moment in debates about whether arbitrator-counsel conflicts and about whether arbitrators have power to disqualify counsel. It also contributed to system-wide innovation in the form of the 2014 IBA Guidelines for Party Representatives in International Arbitration.

Meanwhile, in a similar cautionary tale, in RSM v. St. Lucia the ICSID claimant’s repeated failure to pay tribunal-ordered costs prompted a controversial decision on security for costs, which rested at least in part on the fact that the claimant now had a third-party funder. The facts led to inflammatory language in an assenting opinion, which prompted a subsequent challenge to its author on grounds of bias against funders. More generally, the case fed broader concerns about disclosure of funders.

Today we have several new sources—including the IBA Guidelines, the ICC Practice Note, proposed Hong Kong and Singapore legislation, and some new BITs—which establish standards for disclosure of funders in order to assess potential arbitrator conflicts.

But with apparent glee, certain funders report that these new disclosure standards are systemically disregarded in practice.

This disregard is fine—they argue—because to date there has not been any successful challenge to an award based on an arbitrator conflict with a funder. As the cases described above illustrate, however, it would be profoundly counter-productive if refutation of this view came in the form of an annulment in a highly sensational case.

As a final example, let’s consider critiques of the market for arbitrator services. It is a market characterized by high barriers to entry (experience in numerous cases as an arbitrator, among other credentials), and profound information asymmetries (repeat players have extensive information about arbitrators, compared with newcomers). The result is, not surprisingly, a small cadre of arbitrators who are not regarded as representative of the full range of parties who participate in international arbitration.

Here again, a range of innovations have come in response. Arbitral institutions have made selection criteria more transparent and pressured arbitrators to render arbitral awards more quickly. To expand diversity, law firms and Arbitral Women have sponsored The Pledge, which calls on firms and parties to promote practices to open avenues for women arbitrators.

Despite these changes, more systemic innovation is needed. The prevailing practice of ad hoc, person-to-person phone calls to obtain information about arbitrators is seriously out of date. More importantly, it creates a bottleneck of information that makes the selection process less fair for those who don’t have a large network of people to call, and less efficient and more precarious for who have large networks. The time is now for an upgrade that Arbitrator Intelligence is working to create.

In the coming months, AI will be announcing its new Feedback Questionnaire, which when implemented will systematically gather data about arbitrator decisionmaking. As with other reforms described above, this innovation will seek the international arbitration community’s input on and support for reform aimed at correcting existing inefficiencies and improving its overall functioning.

* * *

In conclusion, despite an increasingly challenging climate, we can take more than a Quantum of Solace from the fact that those professionals active in international arbitration care deeply about the field’s real and perceived legitimacy. The numerous internal reforms described above represent collective efforts to respond to problems and critiques through continued self-reassessment and internal recalibration will ensure that for international arbitration Tomorrow Never Dies.

—————————————————

* The author is the founder of Arbitrator Intelligence, and apologizes to James Bond fans for the immoderate use of 007 puns. A version of this essay was first presented as the Keynote Address at the AIJA New York 8th Annual Arbitration Conference in October 2016.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.

Catherine, why would the survey only seek the international arbitration community’s input on and support for reform?

Thanks for your question, James. The Feedback Questionnaire will seek information from individual cases, and therefore directly from the participants in those cases. It will not be an open invitation to provide open-source feedback on any topic regarding arbitrators. While others have proposed something like a “TripAdivisor for Arbitrators,” we at Arbitrator Intelligence do not believe such an approach would generate the fair and high-quality information that is needed.

Will Arbitrator Intelligence one day publish an annual report or other financial statement? To me, ‘fair and high quality information’ is something that customers do value and will pay for – I’d eventually like to see evidence quantifying those exchanges.