Traditionally, arbitration agreements do not designate the law governing the arbitration agreement. In BCY v BCZ [2016] SGHC 249 (“BCY v. BCZ“), the Singapore High Court clarified the position in relation to the law applicable to the arbitration agreement where such choice is absent. In doing so, the High Court differentiated between the situations where the arbitration agreement sits within a main contract and where it is a freestanding agreement. The decision raises interesting implications which we analyse below.

Background to the dispute

The dispute concerned a sale and purchase agreement for shares in a company (“SPA”). The parties exchanged seven drafts of the SPA but ultimately a final version of the SPA was not signed. The SPA contained an arbitration clause providing for ICC arbitration seated in Singapore, governing law of the contract as New York law and no law was specified to govern the arbitration agreement.

When the plaintiff decided not to proceed with the proposed sale of shares, the defendant commenced ICC arbitration. The plaintiff challenged the arbitrator’s jurisdiction on the ground that no arbitration agreement had been concluded between the parties. The arbitral tribunal found that New York law applied to the arbitration agreement, under which a valid arbitration agreement had come into existence.

The plaintiff appealed the decision of the arbitrator to the High Court under section 10 of the International Arbitration Act (Cap 143A). The issue before the Court was whether an arbitration agreement had come into existence, in accordance with the law governing the arbitration agreement.

Decision of the High Court

Relying on the English Court of Appeal judgment of Sulamérica Cia Nacional de Seguros SA and others v Enesa Engelharia SA and others [2013] 1 WLR 102 (“Sulamérica”), the High Court reiterated that the governing law of an arbitration agreement is to be determined via a three-step test: (a) the parties’ express choice; (b) the implied choice of the parties, as gleaned from their intentions at the time of contracting; or (c) the system of law with which the arbitration agreement has the closest and most real connection.

Since there was no express choice of law to govern the arbitration agreement, the High Court was concerned with part (b) of the above test, i.e., the implied choice of law.

The defendant asserted that New York law, being the law governing the SPA, should govern the arbitration agreement. The plaintiff contended, however, that Singapore law, being the law of the seat, should govern the arbitration agreement. In support, the plaintiff relied on FirstLink Investments Corp Ltd v GT Payment Pte Ltd and others [2014] SGHCR 12 (“FirstLink”) where an Assistant Registrar (an “AR“) held that absent indications to the contrary, the law of the seat will govern the arbitration agreement when the parties have not expressly specified so.

While the Court noted that the parties agreed there was no material difference between New York and Singapore law in respect of whether an arbitration agreement was in existence, the Court nevertheless proceeded to determine the governing law of the arbitration agreement given the divergence of authorities on this issue.

The Court ultimately concluded that there had been no reason for the AR in FirstLink to depart from Sulamérica in favour of a starting presumption for the law of the seat (¶54). The Court also held that the choice of law analysis for an arbitration agreement would differ depending on whether it sits within a main contract or is instead a freestanding arbitration agreement.

1) Arbitration agreement as part of the main contract

The Court held that for arbitration agreements forming part of the main contract the “governing law of the main contract is a strong indicator of the governing law of the arbitration agreement unless there are indications to the contrary” (¶65). The choice of a seat different from the law of the governing contract could justify moving away from the starting point of applying the governing law of the main contract. (¶55). However, it could not in itself suffice to displace the starting position (¶65).

The Court also explained that the default position should only be displaced if the consequences of it “would be to negate the validity of the arbitration agreement, even though the parties themselves had evinced a clear intention to be bound to arbitrate their disputes”. In such circumstances, the law of the seat would govern the arbitration agreement

Further, the Court held that “anything which suggests the parties may not have intended to have their arbitration agreement governed by the same law as the main contract would still be a factor to consider.”

2) Freestanding arbitration agreement

With respect to ‘freestanding’ arbitration agreements, the Court concluded that if there is no express choice of law of the arbitration agreement, the law of the seat would most likely govern the arbitration agreement. The Court acknowledged that freestanding arbitration agreements are rare, and gave two examples (1) in highly complex transactions, where parties enter into a single arbitration agreement covering disputes arising out of several contracts or an overall project; and (2) an arbitration agreement concluded after a dispute has arisen.

Implications – Default laws under the institutional rules

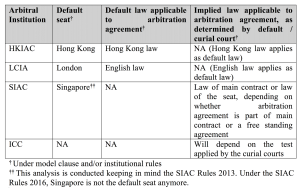

When parties have not expressly agreed the law of an arbitration agreement:

- The Model SIAC clause and the SIAC Rules are silent on what the default law of the arbitration agreement should be;

- Whereas the HKIAC Model clause specifies Hong Kong law as the default law applicable to arbitration agreements;

- Similarly, the LCIA Rules provide that the default seat of the arbitration shall be London and that the default law applicable to the arbitration agreement shall be the law of the seat (English law if the default seat is London), subject to parties’ agreement otherwise.

Thus, taking into account BCY v. BCZ, the law applicable to the arbitration agreement can depend on which institution’s Model Clause and/or institutional rules are adopted:

Conclusion

It is common for international arbitration users to be embroiled in disputes concerning the law applicable to the arbitration agreement where no express choice had been made. This is especially true where parties treat arbitration clauses as “Midnight Clauses” and do not give appropriate attention to carefully drafting an arbitration clause.

In such situations, the BCY v. BCZ decision is certainly a welcome step. BCY v. BCZ attempts to align the Singapore position with the English position (the Sulamerica decision), such that the implied choice of law for the arbitration agreement is likely to be the same as the law of the substantive contract.

BCY v BCZ also represents development of the common law jurisprudence on the distinction it draws between freestanding arbitration agreements and arbitration agreements contained in a substantive contract. Barring any express choice by the parties, the law governing the arbitration agreement which is freestanding is the law of the seat and the law governing the arbitration agreement contained in a substantive contract is the law of the substantive contract.

It will be interesting to observe how courts and tribunals address this distinction in future cases. This is because the distinction can be a difficult one to draw. For example:

- In BCY v BCZ, the alleged arbitration agreement was held to be one that was part of a substantive contract, i.e., an SPA, notwithstanding the fact that the draft SPAs were never signed. The High Court accepted that the arbitration agreement, if it existed, had existed “prior to the conclusion of the [substantive] contract” and was “independent of the SPA“.

- In Viscous Global Investments Ltd v Palladium Navigation Corporation “Quest” [2014] EWHC 2654, cited by the Singapore High Court, there were four bills of lading which each contained / incorporated an arbitration clause. Additionally, there was a subsequent letter of undertaking containing an arbitration clause. The English High Court held that the arbitration clause in the letter of undertaking replaced the four prior arbitration clauses and, thus, regarded the subsequent arbitration clause as a freestanding arbitration agreement. One wonders if the court would have reached the same conclusion if it had regarded the subsequent arbitration clause as merely varying the prior arbitration clauses, as the losing party had contended.

To avoid potentially costly litigation on this issue, it remains advisable for parties to expressly state the law governing their arbitration agreement. As explained above, adopting institutional rules and / or a Model Clause does not always offer certainty.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.

The decisions of the Singaporean courts are becoming more and more an important source for interpreting complicated issues like this one. Very interesting article!