India has long been regarded as an unappealing centre for arbitration – be it as the seat of arbitration or as the place of final enforcement of the arbitral award. Indian judiciary is often quoted to be over interfering in matters of arbitration and enforcement. If fact could replace fiction, in the last decade, Shylock would have a hard time enforcing his rights to his money with little hope of claiming a pound of Antonio’s flesh. The Indian courts wouldn’t shy from reopening and rehashing the proceedings already happened before the Duke of Venice, a twist in the tale that could make Shakespeare rewrite the famous climax and make Portia’s wit of little consequence indeed. While this reputation may have been well-deserved in the decade past, the ground reality since has seen a galactic shift. The legislature and judiciary have together taken upon themselves to ensure this course correction.

In this article we bust the myth that is an enforcement defiant India in context of foreign awards.

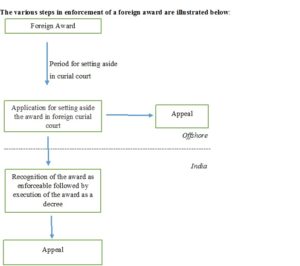

A. The ever-shrinking scope of resisting enforcement of foreign awards in India:

The legislature and judiciary have restricted resistance to enforcement of a foreign award only on established grounds under Section 48 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996 (“Act”) and, in keeping with the view of arbitrally-progressive jurisdictions, have held that executing courts cannot review the award on merits.

Some (the authors included) would even argue that under the present regime, it is easier to enforce a foreign award in India than a domestic one.

i. Foreign-Seated Awards – no longer open to challenge in India:

The myriad of challenges to enforcement of foreign awards in India had become a nightmare for parties seeking enforcement in India. The uncertainty associated with enforcement of foreign awards reached its zenith with Bhatia International v. Bulk Trading S.A. (2002) 4 SCC 105 which laid down that Indian courts would have jurisdiction in international commercial arbitrations, irrespective of the seat of the arbitration. The resulting jurisprudence saw Indian courts not only refusing enforcement but even setting aside foreign awards. The time was ripe for the proverbial hero to emerge and save foreign seated arbitrations from the un-welcome interventions by Indian Courts. In September 2012, a five judge bench of the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India delivered its much celebrated decision in BALCO v. Kaiser Aluminium (2012) 9 SCC 552 which ousted the jurisdiction of Indian courts in foreign-seated arbitration. Post BALCO, foreign awards cannot be challenged in India. (However, this judgment was applied prospectively, to arbitral agreements executed after 6 September 2012 i.e. the date of the judgment.)

ii. “Patent Illegality” no longer a ground of resisting enforcement of foreign awards:

The introduction of the test of “patent illegality” to the already infamous ground of “public policy”, as interpreted in ONGC v. Saw Pipes (2003) 5 SCC 705, meant that enforcement of a foreign award in India could be challenged on the basis that the foreign award was contrary to the substantive law of India or in contravention of contractual terms etc. – determinations which ought to be in the sole remit of the arbitrator.

After almost a decade, the scope of challenge was restricted in Shri Lal Mahal Ltd. v. Progetto Grano SPA (2014) 2 SCC 433 wherein “public policy” under Section 48(2)(b) of the Act was narrowly interpreted and the recourse to the ground of “patent illegality” for challenging enforcement of foreign awards was no longer available.

The pro-arbitration shift in the judicial mindset can also be gleaned from the fact that the in judgment Shri Lal Mahal Ltd., the Supreme Court (speaking through Hon’ble Mr. Justice R.M. Lodha) overruled its own ruling in Phulchand Exports Limited v. O.OO. Patriot (2011) 10 SCC 300 (an earlier judgment delivered by Justice Lodha himself – wherein the Supreme Court had ruled that a party could resist enforcement of a foreign award on grounds of “patent illegality”).

As the statute reads today, even domestic awards cannot be vitiated on grounds of being patently illegal in India-seated international commercial arbitrations. (Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996, section 23(2A))

iii. A foreign award need not be stamped under the Indian Stamp Act:

A domestic award may be refused enforcement if it hasn’t been adequately stamped, in accordance with laws of India. However, resisting enforcement of a foreign award on the ground that it is not stamped as per the Indian law, has been shunned as a frivolous ground for delaying and obstructing enforcement of foreign awards. (See Naval Gent Maritime Ltd. v. Shivnath Rai Harnarain (I) Ltd. (2009) 163 DLT 391 (Del))

iv. Intention to arbitrate is paramount:

In a recent appeal, the Supreme Court upheld the finding of the Bombay High Court that in a foreign seated arbitration (and resultant award), an un-signed arbitration agreement would not defeat the award. (See Govind Rubber v Louids Dreyfus Commodities Asia P. Ltd. (2015) 13 SCC 477) The court preferred to give primacy to the intention and conduct of parties for construing arbitration agreements over the mandate of the parties’ signatures required in the agreement.

v. Burden of proof on the resisting party:

Similarly, in a recent ruling, the Bombay High Court placed a “higher burden on party resisting enforcement of giving necessary proof which stands on higher pedestal than evidence” than the burden on the party seeking enforcement of a foreign award, who is only expected to produce necessary evidence. (See Integrated Sales Services Ltd., Hong Kong v. Arun Dev s/o Govindvishnu Uppadhyaya & Ors. (2017) 1 AIR Bom R 715)

vi. No third party or the Government can object to enforcement of a foreign award:

With the Supreme Court taking the lead in a consistent pro-enforcement approach of foreign awards, the High Courts have also been keeping up with the pace, with the High Court of Delhi being the harbinger in this respect. In NTT Docomo Inc. v. TATA Sons Ltd (2017) SCC OnLine Del 8078, the Delhi High Court allowed enforcement of an LCIA award after rejecting the Reserve Bank of India’s objections that the underlying terms of settlement (wherein the Indian entity, Tata Sons, was required to pay $1.17 billion to NTT Docomo, a Japanese company) would be against the public policy of India. The Delhi High Court held that since RBI was not a party to the award, it could not maintain any challenge to its enforcement.

vii. Reciprocating countries for enforcement of foreign awards outnumber the ones for foreign judgments:

48 countries have been notified by the Central Government of India as “reciprocating countries” under the New York Convention, while only 12 nations have been recognized as reciprocating countries under Section 44A of the Code of Civil Procedure for execution of foreign judgments. In respect of judgments emanating from the remaining countries, the parties seeking execution would have to file a suit in India and place in evidence the underlying foreign judgment.

B. The legislative intent: Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act 2015

Consistent with the pro-enforcement approach adopted by Indian courts, the recent legislative changes to the Act vide the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act 2015 clarify the extent to which a foreign award can be said to be in conflict with the public policy of India. Subsequent to these amendments, only the following cases amount to violation of “public policy” under Section 48 of the Act:

i. the making of the award was induced or affected by fraud or corruption or was in violation of section 75 or section 81 of the Act; or

ii. it is in contravention with the fundamental policy of Indian law; or

iii. it is in conflict with the most basic notions of morality or justice.

The tests for these grounds have been summed by the Supreme Court in Associate Builders v. Delhi Development Authority (2014) (4) ARBLR 307 (SC). It has been further clarified that “the test as to whether there is a contravention with the fundamental policy of Indian law shall not entail a review on the merits of the dispute.” Such amendments are to be seen as strong measures in response to the infamous perception of India being liberal to the challenges to enforcement of arbitral awards on grounds of “public policy”.

Furthermore, subsequent to these amendments, even after making of the arbitral Award, a successful party which is entitled to seek the enforcement of the award can apply to the court under section 9 of the Act, for protection by grant of interim measures, pending enforcement of the foreign award. (See, Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996, section 2(2) proviso)

C. Protectors of the Realm: Commercial Courts in India

The Indian legal system continues to face criticism on account of the time taken in disposal of cases. Thus, with the objective to accelerate disposal of high value commercial disputes, Commercial Courts, Commercial Division and Commercial Appellate Division of High Court Act, 2015 (“Commercial Courts Act”) was enacted.

Under this regime, specialized commercial courts were set up for speedy and effective dispute resolution of all commercial disputes.

The Commercial Courts Act also provided that proceedings emanating from arbitrations (both foreign and domestic), where the subject matter is a commercial dispute, would also be heard and disposed of by the Commercial Courts (Commercial Courts Act, section 10). The statute amended the application of the extant Code of Civil Procedure 1908 to commercial disputes, provided for a mechanism for speedy resolution, and a much needed requirement of appointment of only those judges which have experience in dealing with commercial disputes. (Commercial Courts Act, sections 4, 5)

“Change is the end result of all true learning”

Liberalization of policies and clarified norms of doing business in India have made investments more lucrative and attractive. However, to truly sustain its growing global credibility, India needed to deal with the elephant in the room.

His Lordship Justice D. Desai in 1982, of the Supreme Court of India had, in relation to the then extant arbitral laws, observed that “the way in which the proceedings under the Act are conducted and without exception challenged in Courts, has made Lawyers laugh and legal philosophers weep” (Guru Nanak Foundation v Rattan Singh (1982) SCR (1) 842). India has since come a long way. In face of the legislative and judicial changes brought in and the evident shift in the judicial mindset, India’s current reputation of being enforcement unfriendly is largely undeserving and a remnant of the decade past – the Bhatia Raj. India is no longer emerging as a pro-arbitration and pro-enforcement jurisdiction. It has already arrived. Sit-up and take notice!

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.