On 6 March 2018, the Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU“) issued its long-awaited decision in the Achmea case (C-284/16) between the Slovak Republic and Dutch insurer Achmea BV.

In Achmea, the CJEU found investor-state dispute settlement provisions in investment treaties concluded between EU Member States (“intra-EU BITs“) to be incompatible with EU law.

The judgment will fundamentally change the landscape for arbitration in Europe, and it has been argued that as a logical consequence, EU Member States now have an obligation to amend or terminate their BITs under EU law.

The Netherlands: We Will Terminate Intra-EU BITs Through a New Multilateral Treaty

Indeed, it did not take long for the Dutch government to announce its intention to terminate all intra-EU BITs to which the Netherlands is a party. On 26 April 2018, the Dutch Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation stated that, following the Achmea judgment, the Netherlands saw “no other option” than to terminate its bilateral investment treaty with the Slovak Republic.

Minister Sigrid Kaag set out the government’s view in a letter addressed to the Chairperson of the Dutch House of Representatives. Acknowledging the impact of the Achmea judgment, the letter confirms the Dutch government’s intention to terminate its investment agreement with the Slovak Republic.

Besides the Netherlands-Slovak Republic BIT, the government will also seek to terminate the other 11 investment agreements concluded between the Netherlands and other EU Member States (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania and Slovenia). This, the letter explains, will be done by negotiating a single multilateral treaty for reasons of “clarity, speed and efficiency”.

Interestingly, the Dutch government’s decision to terminate intra-EU BITs does not apply to the Caribbean Netherlands (i.e. the islands of Bonaire, St Eustatius and Saba). Although they are “special municipalities” and considered to be “public bodies” under Dutch law, they are overseas territories of the European Union, a special status under which EU law does not automatically apply. As a result, according to the government, it is up to these municipalities to decide whether or not they want to terminate intra-EU BITs.

The letter addresses another hot topic: the application of Achmea to the Energy Charter Treaty (“ECT“). Signed in 1994, the ECT has generated more investor-state claims between the EU Member States than any other treaty. The Achmea judgment generated a lot of discussion on whether or not a similar argument could be made to render intra-EU claims brought under the ECT illegal under EU law.

On this, the European Commission has made it very clear where it stands: in its view, the ECT does not apply to investors from other Member States initiating disputes against another Member State (see, for example, paragraph 163 of decision SA.4038 in November 2017). Without going that far, the Dutch government nevertheless acknowledges that Achmea “is also relevant” to the dispute settlement mechanism contained in the ECT.

The Writing Is on the Wall for Remaining Intra-EU BITs

There are over 190 intra-EU BITs. Many of these were agreed in the 1990s, before the EU enlargements of 2004, 2007 and 2013. They were mainly struck between existing members of the EU and those who would become the “EU 13”.

According to the European Commission, those agreements’ raison d’être was to provide reassurance to investors who wanted to invest in the future “EU 13”, by strengthening investment protection (e.g., through compensation for expropriation and arbitration procedures for the settlement of investment disputes).

Situated mostly in Central and Eastern Europe, those countries later joined the EU. This opened up a debate on the validity of intra-EU investment treaties. The European Commission took an increasingly active role in challenging intra-EU investment agreements, through amicus curiae interventions, suspension injunctions and initiation of infringement proceedings.

In 2012, Ireland ended all its intra-EU BITs, followed by Italy in 2013.

In 2015, the European Commission formally requested Austria, the Netherlands, Romania, the Slovak Republic and Sweden to end the intra-EU BITs between them, by sending letters of formal notice, i.e. the first stage of the general EU infringement procedure in article 258 of the TFEU.

In 2016, Denmark reportedly reached out to its EU counterparts to suggest mutual termination of intra-EU BITs. The same year, Austria, Finland, France, Germany and the Netherlands also proposed an EU-wide agreement to replace existing intra-EU BITs.

In 2017, Romania formally terminated all of its intra-EU BITs. The same year, Poland initiated the termination of its BIT with Portugal, the first of 23 similar agreements which Poland said it would terminate.

BIT by BIT, EU Member States are inexorably moving towards the termination of all intra-EU investment treaties. The European Commission’s determination to challenge those agreements, and its strong push towards a Multilateral Investment Court, were but one nail in the coffin of intra-EU BITs. In the wake of Achmea, it could be that the Member States consider that they have “no other option” but to end all intra-EU BITs.

The ‘Big Crunch’ of Investor-State Arbitration?

Taking a step back, we see that the Achmea judgment, and the Netherlands’ decision to terminate intra-EU treaties, should have been unsurprising to arbitration practitioners.

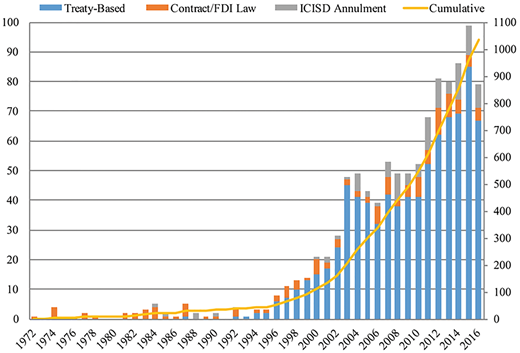

Over the last twenty years, investment treaty-based arbitration has grown exponentially (see Figure 1 below).

FIGURE 1 – International investment arbitration cases registered by year (1987–2016). PITAD, PluriCourts Investment Treaty Arbitration Database (PITAD) as of 1 January 2017; 831 cases in total through 1 January 2017. Source

But after investment treaty-based arbitration’s ‘big bang’ is there a ‘big crunch’ to come? It is now commonplace for commentators to note that investment treaty arbitration has suffered an accelerating backlash in the last few years. In that sense, Achmea is only the latest manifestation of that phenomenon, and the Netherlands’ decision a natural consequence of this evolution.

What are the causes of this backlash against investment arbitration? Although many explanations have been offered (from the panels’ rigid views of contracts to the growing number of cases brought –and won- by investors against sovereign states), two in particular merit singling out. They not only reflect past sentiment about investment arbitration, but also offer a glimpse into the future of investment arbitration as a whole. These two reasons are the pushback against globalisation and the increasing importance of regionalism.

Backlash Against Globalisation and Corresponding Rise in Nationalism

Commentators have frequently mentioned that the US 2016 presidential elections and the Brexit vote were both built on the rejection of globalisation and expressed a wish, on the part of the American and British people, to re-centre policies around nationalism and domestic sovereignty.

President Trump’s proposal to renegotiate NAFTA has led to speculation as to what (if any) investor-state dispute settlement mechanism will be included in the renegotiated treaty.

In Europe, the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) and Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) were perceived by the general public as imposing North American rule(s). This translated into a rejection of investor-state dispute mechanisms as ‘secret courts’. The Brexit vote was another symptom of this desire to ‘take back control’.

Another sign of the nationalist wave sweeping the globe is the resurgence of resource nationalism – in the Americas, in Africa, in Asia. Will Europe be the next continent to experience increased nationalism in investment protection?

Focus on Regional Mechanisms, Including in Europe

Over the last decade, many states around the world overhauled their investment protection system and terminated some, and sometimes all, of the BITs they were party to.

In 2012, South Africa terminated its BIT with Belgium-Luxembourg and issued cancellation notices for its BITs with Germany and Switzerland.

In 2014, the Indonesian Government indicated that it would terminate all of its 67 bilateral investment treaties.

In 2016, India served notices to 57 countries including the UK, Germany, France and Sweden seeking termination of BITs whose initial duration has either expired or will expire soon.

In 2017, Ecuador terminated all 16 of its remaining BITs, having previously ended treaties in 2008 and 2010.

A global pattern starts to emerge, with various states terminating BITs and relying on regional multilateral frameworks instead.

For example, Indonesia explicitly embraced regionalism in its approach to foreign investment, relying on the ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement (which provides BIT protections, including investor-state dispute settlement provisions).

Similarly, in 2017 MERCOSUR signed a Protocol on Investment Cooperation and Facilitation, which coordinated the regional bloc’s approach to investment disputes and most notably excluded investor-state arbitration.

Regional instruments are being increasingly used to grant investment protection, and regional organisations are a force to be reckoned with on the international investment legal scene.

This is, of course, particularly poignant in Europe. As noted above, the European Commission has been a vocal opponent of intra-EU treaties. It recently received the green light to negotiate, on behalf of the European Union, a convention establishing a multilateral court for the settlement of investment disputes (the “MIC”). The MIC would be Europe’s permanent body to settle investment disputes, eventually replacing the bilateral investment court systems included in EU trade and investment agreements.

Much has been written about Achmea and its consequences. However, it is crucial for practitioners and academics to also look at the judgment through a global and cross-disciplinary lens.

In particular, the investment arbitration community would be well-advised to actively engage with regional organisations and to take heed of the growing discontent against investor-state dispute mechanisms.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.