The Arab Spring erupted in Tunisia in December 2010 and quickly spread to Egypt, Libya, Yemen, Bahrain, and other countries of the Arab World in 2011 and 2012. As I wrote in a 2015 Kluwer Arbitration Blog post, The Evolution of Arbitration in the Arab World, the uprisings of the Arab Spring and the political changes resulting therefrom were expected to have a significant impact on the international arbitration landscape with a surge of new investment cases anticipated against Arab states.

Increase of ICSID Cases from the Arab World in the Aftermath of the Arab Spring

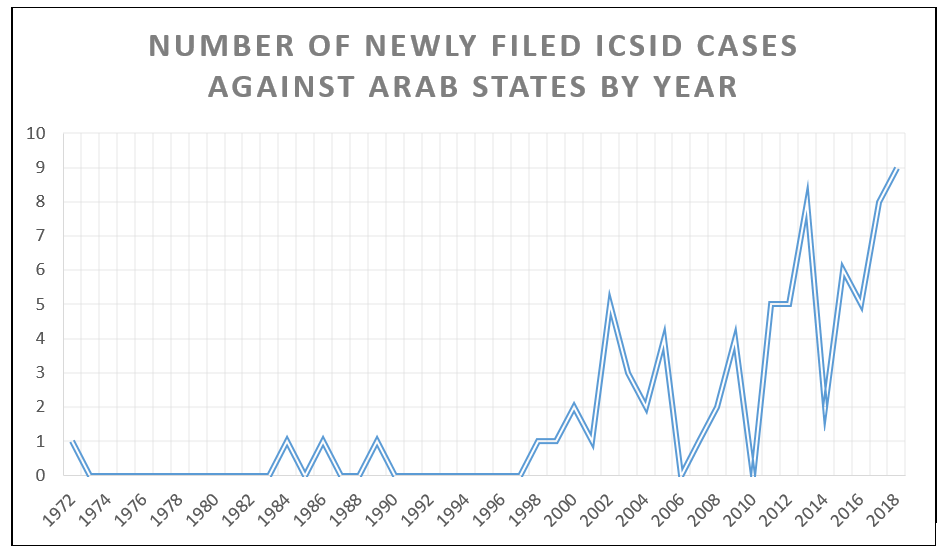

As expected, the number of newly filed ICSID cases from the Arab World did indeed rise sharply in the period from 2011 to 2018. As shown in the graph below, since 2011, the average number of newly filed cases with Arab state respondents has been 6 per year, with 8 new cases in 2013 and 2017 and 9 new cases in 2018.

While there has been a general increase in the number of newly filed cases on ICSID’s docket during the period of 2011-2018 (not dropping below 38 since 2011 and rising as high as 56 in 2018), the percentage of newly filed cases involving Arab state respondents has also risen, representing on average 12.6% of newly filed ICSID cases and rising as high as 20% of newly filed ICSID cases in 2013. Most recently in 2018, 16% of newly filed ICSID cases (9 out of 56) came from the Arab World.

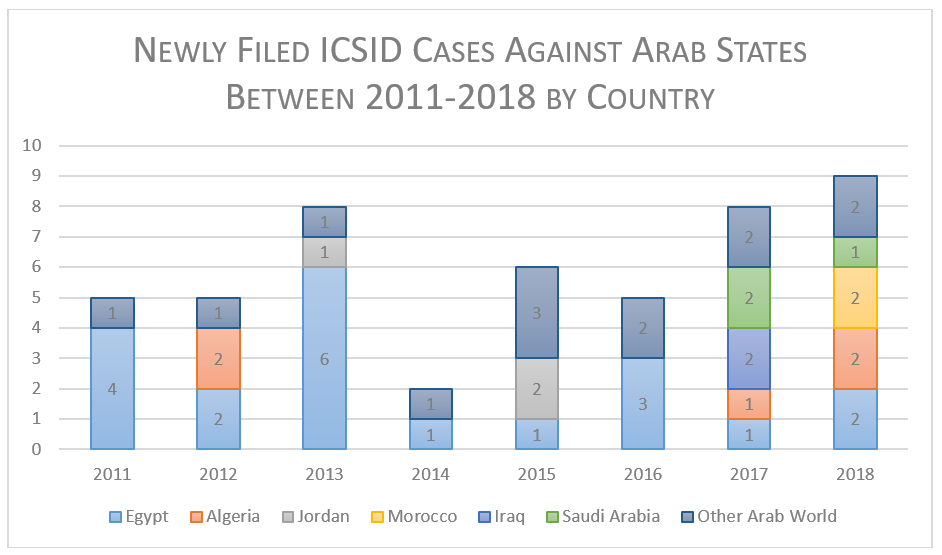

In addition, as shown in the graph below, while the respondent states from the region have become increasingly diverse, Egypt has remained the most frequent respondent state with 20 new cases filed against it between 2011 and 2018. The highest number of new cases brought against it in one year were 6 in 2013. Far behind Egypt, Algeria was confronted with 5 new cases in the 2011-2018 period, and Jordan and Saudi Arabia were both confronted with 3 each.

Despite the increasing number of new cases filed against Arab respondent states, the outcomes have not always been favorable for investors. A number of cases brought by investors have been dismissed on jurisdictional grounds (i.e. National Gas) or resulted in liability decisions in favor of the respondent state (i.e. Veolia and Al Tamimi). An even larger number of cases have settled (at least 12 since 2011, i.e. Bawabet Al Kuwait, Sajwani, Indorama, and LP Egypt), which leads one to question whether investment arbitration may have been increasingly employed during this period as a tactical mechanism for obtaining amicable settlement.

The Invocation of Arab Spring Events in Recent Arbitration Cases

Of the 20 newly initiated cases against Egypt in the past 8 years, only some have directly dealt with the events of the Arab Spring in the assessment of the parties’ factual or legal arguments or defenses. Many cases have seemingly not made a direct reference thereto (although the details of these recently filed cases have still not fully come to light) including a dispute on the cancellation of a contract for the development of a new city south of Cairo, a mining dispute, and a water and sewage distribution dispute, among others.

However, other cases dealing with the actions recently taken with respect to commitments made to investors by the former Egyptian regime have been a topic discussed in depth. Such cases include: Damac, in which a Dubai-based investor had asserted violations of the UAE-Egypt BIT for his conviction in absentia by Egyptian courts due to his company’s acquisition of land far below market value during the former regime; Indorama, in which a 2011 Egyptian court annulled the 2007 privatization of a previously state-owned industrial asset under which an Indonesian investor had acquired the asset; and Bawabet Al Kuwait, in which the government withdrew its establishment of an investment free zone in Egypt.

Other cases against various respondent states, both in the investment and the commercial context, have examined select events of the Arab Spring uprisings which have been raised by claimants and respondents alike to support their positions. A few of these cases will be briefly discussed below.

The Defense of Necessity

In the Unión Fenosa ICSID case, a Spanish gas company brought a case against Egypt. The respondent state Egypt invoked, among other arguments, the doctrine of necessity under customary international law to defend against its shutting down of the Damietta LNG plant. It claimed that its prioritization of supplying natural gas to feed domestic electricity in Egypt rather than export it as agreed with the concerned investor was an act of necessity which was the only way to maintain Egypt’s security, public order, and stability, safeguard its essential interests, and maintain its basic services in the face of “grave and imminent peril”.

Egypt referenced the historic levels of violence, riots, and clashes in the country which allegedly constituted a threat to “the basic functioning of society and the maintenance of internal stability”. It claimed that these events caused a “dramatic drop in the supply of natural gas both internally and for exportation” which led to repeated blackouts and more widespread violence and unrest. Egypt claimed that if it had not prioritized its domestic needs, the situation at the time would have become far worse.

However, in its 2018 award, the Tribunal found that a number of elements were missing to legitimize Egypt’s necessity defense. It found that the timing was off. The Egyptian Revolution began in 2011, however it was only in 2013 that the respondent made any suggestion that the social and political instability in Egypt was a force majeure event. And despite the revolution having ceased in 2015, gas supplies did not resume at that point in time.

In addition, the Tribunal found that the events of the Egyptian Revolution could not be the proximate cause of curtailing gas supplies to the plant because such curtailment occurred both prior to and following the Egyptian Revolution.

Furthermore, the tribunal found that the act of the government was not the “only way” to maintain Egypt’s security situation. In fact, there was a stark disproportionality in the reduction of gas delivered during the relevant period where other users saw a reduction of only between 12% and 60%, whereas the Claimant investor suffered a curtailment of 96%.

The Tribunal therefore held that the Egypt failed to prove the defense of necessity under customary international law.

Seeking to Break the Causal Link

In the Olin Holdings ICC case against Libya, a Cyprus investor sought compensation for Libya’s alleged expropriation of the land in which it had invested to build a dairy and juice factory. Libya argued that the element of causation was missing from the Cyprus investor’s case, asserting among other arguments that the harm it may have suffered in the post-February 2011 time period was the result of the chaos arising out of the Libyan Revolution and not from acts attributable to the Libyan state.

However, in its 2018 award, the Tribunal was unconvinced by Libya’s line of argument. It held that while the events of the Libyan Revolution and civil war may have had a general impact on the investment climate post-2011 and may have contributed to the underperformance of the Cyprus investor’s business, those events would not be sufficient to address the investor’s underperformance prior to 2011. When compared to other market entrants around the same time period as the Cyprus investor, another competitor with similar initial investments at the outset of its investment in 2006 was able to make large profits in a short period of time and maintain its position as a market leader even today, despite the events of the Libyan crisis.

This, among other factors, led the Tribunal to conclude that the events of the Libyan crisis “cannot be considered as an event that breaks the causal link between Libya’s breaches of the BIT and Olin’s underperformance after 2011”.

Invoking Force Majeure As A Claimant

In the Gujarat ICC case, a group of Indian investors sued the Yemeni state and one of its ministries, seeking among other claims, declaratory relief that an event of force majeure continuing for six months existed and that the contracts in question were validly terminated.

The Tribunal recalled in its 2015 award that as of January 2011, the security situation in Yemen had begun to deteriorate, with increased instances of tribal clashes, attacks, and kidnappings leading up to the declaration of a State of Emergency on 18 March 2011 by the Government. It stated that a number of such events occurred on multiple occasions and in various locations from March 2011 to February 2013 and were beyond the reasonable control of the claimants.

The three claimants suggested that those events fell within the definition of force majeure contained in the relevant contracts and relied upon the clause in question to send a notice to the respondent state automatically suspending its obligations under the contracts. A further contractual clause provided that if the force majeure situation would continue for a period of six months, the Claimants would have the option to terminate their obligations.

The Tribunal agreed with the Claimants that an event of force majeure existed and continued for a period of six months and that as such the Claimants had validly terminated the contracts.

State’s Right to Improve Workers’ Wages

While the three cases above involved scenarios where investors prevailed, the 2012 ICSID case Veolia Propreté resulted in a decision dismissing the investors claims and ruling in favor of the respondent state. In that case, a 2018 award dismissed a claim involving a long-term waste management contract in the Egyptian governorate of Alexandria in which Veolia sought compensation for alleged damage resulting from an increase in the minimum wage following a change in the labor law.

While the award remains unpublished, the press has reported that the tribunal dismissed the investor’s claim that the change in the relevant labor law caused damage to its investment, conduct allegedly prohibited by the Egypt-France BIT. The labor law in question dates back to 2003, however the issues raised by this case, notably the juxtaposition between changes in workers regulations and assurances provided to investors in long-term contracts, are likely to arise in other cases in the aftermath of the Arab Spring. Indeed, issues of workers’ rights have been at the forefront of many Arab Spring demonstrations, for example the 2011 labor protests in the textile factories of Mahalla, Egypt.

Conclusion

It remains to be seen how Tribunals will continue to deal with attempts by states and investors alike to have the events of the Arab Spring and the political and social uprisings which may follow taken into account.

While investors have been successful in some instances in invoking such events, state respondents have also prevailed on jurisdictional and liability claims. These facts, taken as a whole, demonstrate that while some investors may have legitimate claims which were exacerbated by or conduct that was excused by the political events of the Arab Spring, others may have brought increasing numbers of meritless claims or attempted to use such events as a tactical mechanism to leverage the possibility of settlement.

In order to successfully utilize such events to one’s advantage, it follows from the cases discussed above that investors and states alike must be very precise in their invocation of such facts. Simple reference to political events without a clear temporal connection to particular action or inaction will likely be unsuccessful. However, when political happenings are invoked during the progression of dealings between the parties, in official correspondence, and employed in real time as a justification for taking certain action, they are more likely to be seen as legitimate as opposed to an after-the-fact attempt to cover a party’s conduct.

In any event, a large number of cases from 2011 to 2018 have not yet provided conclusory findings. As mentioned above, the details of many cases from the 2011-2018 period, which have either settled or been discontinued, have not been publicly disclosed. Furthermore, around 30 ICSID cases from the 2011-2018 period are still pending.

As more cases continue to be introduced, as pending cases are resolved, and as the political situation in the region continues to remain largely in flux, a clearer picture of the relevant standards to be applied to such political events should come to light.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and should not be regarded as representative of, or binding upon the author’s law firm and its clients.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.