As the number of investor-state disputes grows, so does the number of applications for provisional measures. The recent empirical study conducted by the British Institute of International and Comparative Law and White&Case suggests that investors were more than twice as likely to obtain positive decisions on their requests than respondent states. The study also showed that the geographical region of the respondent states strongly correlated with the outcomes.

Parties request provisional measures, also known as interim measures, interim relief or interim measures, to refrain from aggravation of the dispute, stay parallel proceedings or take other measures to preserve the investments and the exclusivity of investor-state proceedings.

Different outcomes under different arbitration rules

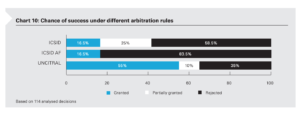

The choice of applicable arbitration rules affects procedural rights of the States and investors, as well as the powers of investor-state tribunals. All major modern arbitration rules contain provisions dealing with the tribunals’ authority to make decisions on provisional measures. The majority of public decisions in investor-state disputes were rendered under the ICSID Arbitration Rules, UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules and ICSID Additional Facility rules.

Although arbitration rules have similar provisions dealing with provisional measures and contain little detailed guidance, the study showed that the outcomes of provisional measures application differ. For example, UNCITRAL tribunals were almost twice as likely to grant requests for provisional measures compared to ICSID tribunals.

The tribunals acting under the ICSID Additional Facility Rules granted half of the investors’ requests and none of the requests made by respondent states. It must be noted that the overall number of publicly-available requests under the ICSID Additional Facility rules remains very limited.

The breakout by the party also points to significant differences between UNCITRAL and ICSID practices. The UNCITRAL tribunals granted or partially granted investors’ requests for provisional measures in more than 70% of cases and the respondent state’s requests in only a third of all cases. Investors’ more often succeeded with their requests in the ICSID tribunals.

It is unlikely that different outcomes under different arbitration rules can be satisfactory explained by the “stronger” wording of the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, allowing the tribunal to “order” rather than “recommend” provisional measures. Provisional measures decisions under the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules are less frequently published compared to decisions under ICSID Rules.

Respondent States less successful with requests for provisional measures

Overall, investors end up being almost two times more successful than states in provisional measures applications regardless of applicable arbitration rules. Two possible explanations can clarify why states so frequently fail in their applications.

First, the total number of their applications was much lower than that of investors. Nearly 70% of all requests were made by investors because states usually have all the necessary tools to achieve their goals without the help of tribunals (e.g., courts, law enforcement agencies, access to documents). Second, the vast majority of applications were requesting security for costs, which tribunals currently view with great scepticism as discussed in more detail below.

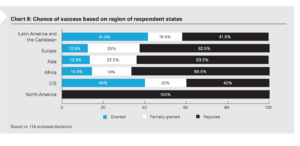

Success of investors correlates with the region of the respondent state

The BIICL/White&Case study shows significant differences in outcomes depending of the region of the respondent states. For instance, requests for provisional measures against North American states fail in 100% cases, while in those concerning the CIS region, as well as Latin America, investors successfully requested such measured in around 40% cases. Over 80% of claimants came from North America and Europe and only around 20% of requests for provisional measures were made against states from these regions.

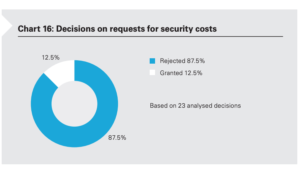

Security for costs requests fail in the vast majority of cases

Investor-state arbitration is notorious for its costs. The costs often reach millions or even tens of millions of US dollars. Investors often operate through local subsidiaries with little assets of their own or rely on third-party funding to make their claims. Not surprisingly, respondent states may have legitimate concerns over investors’ abilities to cover the respondents’ costs if they prevail and often request that the tribunal order the investor to grant them security for their potential costs. Requests to provide security for costs were made in almost every fifth application for provisional measures.

However, the BIICL/White&Case study shows that arbitral tribunals were ready to grant security for costs only in the most extreme circumstances. Until 2014, none of the investor-state tribunals had granted security for costs. Subsequently, in nearly 90% of cases, tribunals rejected respondent states’ requests for security for costs. It appears that only one tribunal granted security for costs on its own initiative without an express request for it from the respondent state (Chevron Corporation and Texaco Petroleum Corporation v. The Republic of Ecuador). That was done to counterbalance the provisional measures it granted to the investors.

Tribunals offer different justifications for not awarding security for costs requests. In Victor Pey Casado and President Allende Foundation v. Republic of Chile the tribunal rejected the request due to the respondent’s failure to show the likely risk of non-payment by the investor. In Emilio Agustín Maffezini v. Kingdom of Spain the tribunal decided that security for costs could not be granted as it did not relate to the subject matter of the dispute.

In fact, no tribunal had ever ordered security for costs before RSM Production Corporation v. Saint Lucia. In that case, the tribunal decided to grant security for costs, first temporarily in its 2013 decision and then for the duration of the case in 2014. The extreme facts of that case showed the high threshold of proving the necessity of security for costs and included the investor’s failure to pay the advances on costs in two prior arbitrations. Overall, the tribunals remained reluctant to order security for costs and they order this type of provisional measure only in the most extreme circumstances.

The BIICL/White&Case study demonstrates that although the approaches of different tribunals to request for provisional measures vary, as the number of decisions grows, it becomes easier to predict their reasoning, which helps to facilitate legal certainty. The authors hope that this study, to be updated regularly, will become an anticipated development in the field of investor-state arbitration.

Full study: David Goldberg, Yarik Kryvoi, Ivan Philippov. Empirical Study: Provisional Measures in Investor-State Arbitration, BIICL/ White & Case, London, 2019.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.