Traditionally, nationality for corporate entities has been regulated by national law, often by reference to whether a corporation has a seat in a country or was incorporated under its laws. However, international investment law has departed from the generally accepted rules of international law on the nationality of corporate persons.

Already in the 1960s, the drafters of the ICSID Convention noted that the system of international investment law could add further criteria which would help qualify investors as ‘foreign’. More specifically, they agreed to include the criterion of control in the ICSID Convention. Qualifying investors as foreign on the basis of control rather than place of incorporation or business has also appeared in various international investment agreements.1)See, e.g., Documents Concerning the Origin and the Formulation of the Convention. Volume II, Part 1. pages 78-80.

The British Institute of International Law (BIICL) and Baker McKenzie recently concluded a study examining how international tribunals approach the use of corporate restructuring by corporations to benefit from international investment agreements. It sheds light on how tribunals approached this question in the past and, to some extent, will help shape legitimate expectations of parties involved in investor-state disputes in the future.

Separating Domestic and Foreign Companies

Foreign investors may prefer to incorporate locally for many reasons but most frequently they do so because of tax considerations. Host states themselves frequently require foreign-owned companies to be locally incorporated to qualify for government procurement, to benefit from subsidies, to enter certain sectors of the economy or for other reasons. If such companies are not treated as ‘foreign’, a large proportion of foreign investment would not be protected by international law.

However, separating truly foreign from domestic companies often presents challenges to investor-state tribunals since most investment treaties aim to protect foreign, rather than domestic investors. This led many tribunals to pierce the corporate veil in order to reveal the shareholders or natural persons affected by adverse actions of the host state.

The existence of corporate groups with complex ownership structures, nominees and various forms of disguised ownership further complicates the determination of whether an investor is foreign and is, thus, eligible for protection under international investment agreements. Investor-state tribunals have developed different approaches on whether the effective control of a claimant over a relevant entity must be merely legal or also factual.2)See also footnote 25 of the report listing a number of cases where tribunals took very different approach on this matter. That has resulted in what some states view as frivolous claims which harm the reputation of host states, and generate a regulatory chill, as was recently discussed by the UNCITRAL Working Group III.

Corporate Restructuring as an ISDS Problem

The currently ongoing investor-State dispute settlement reform discussions touched upon corporate restructuring. Although the UNCITRAL Working Group III has not yet addressed the issue of corporate restructuring in great detail, concerns were expressed with respect to the lack of mechanisms to address frivolous or unmeritorious claims (para. 122), including limitations on the standing of investors (para. 118) and divergent interpretations relating to jurisdiction and admissibility (para. 15).

All these problems may involve determining the nationality of the investor, whether it can be treated as foreign and thus eligible for treaty protections. Usually answering these questions requires interpretation of broad treaty standards in the absence of detailed guidance in the treaty itself. Both the parties and tribunals may also struggle to get a good sense of whether there was a consensus on issues of corporate restructuring and investment protection in dozens of earlier arbitral awards dealing with similar issues.

In the context of investor-state disputes, the term ‘corporate restructuring’ usually refers to decisions to incorporate companies in certain jurisdictions to benefit from more favourable conditions, most commonly related to tax matters but also to investment treaty protections. The Corporate Restructuring and Investment Treaty Protections study demonstrates when such restructuring is seen as permissible under international investment agreements and when the respondent states successfully object to the jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunals.

State Objections Based on Corporate Structuring

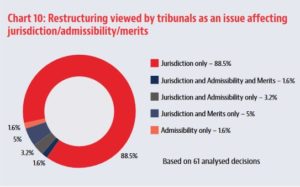

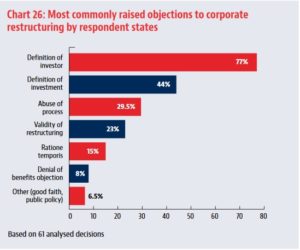

The BIICL/Baker McKenzie study shows that the top five most successful objections of respondent states were based on the interpretation of the relevant treaty clause, the timing of restructuring, the existence of genuine economic activities of the claimant entity as well as examination of the underlying reason for corporate restructuring (including the abuse of process).

In practice, tribunals distinguish between original investment structuring and subsequent restructuring. Where the claim is brought by the original investor, tribunals tend to abide by the strict wording of the treaty. But where the claimant is not the original investor, the tribunals are more likely to apply additional criteria, e.g. considering whether the corporate restructuring was an abuse of process or applying the Salini test for identifying an investment.

For example, the Phoenix Action Ltd v. Czech Republic case involved the insertion of an Israeli entity into a domestic Czech investment structure after a dispute with the government had arisen. The respondent state’s objection prevailed on the sole basis that the investment was not bona fide, as the local entities were acquired at a later stage with the sole purpose of benefiting from the Israel-Czech Republic investment treaty.

While the study found no meaningful effect of differences between various applicable arbitration rules (e.g. ICSID, UNCITRAL or ICSID Additional Facility), the exact language of the relevant treaty matters. For example, in nearly 80% of cases, investors succeeded with overcoming the jurisdictional objections of respondent states because tribunals held that there was no scope to imply any additional requirements into the definitions of ‘investor’ and ‘investment’.

Timing of Restructuring and Genuine Economic Activities Matter

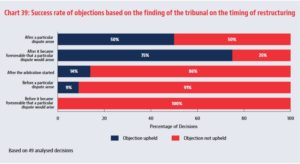

Investor-state tribunals pay particular attention to whether the restructuring was effectuated before or after the dispute arose and whether such dispute was foreseeable to the investor at the time of the restructuring. Such analysis was also key as part of the ‘abuse of process’ objection. Where the investment structure was in place from the outset, only in one fifth of all cases respondent states succeeded with their objections.

Moreover, if the tribunals find that the company engaged in a genuine economic activity in the respondent state, in nearly all cases, the investors were able to overcome jurisdictional objections. In the absence of such activity in the respondent state, tribunals almost always agreed with the respondent state’s objections (90%).

In the absence of detailed guidance in relevant international treaties, tribunals have significant freedom in deciding on the permissibility of corporate restructuring. However, certain trends have already crystallised and are likely to prevail in practice. These trends can also subsequently find reflections in reformed international investment agreements or practice of investor-state tribunals. Also, these findings will help investors to structure their business activities in order to benefit from international investment agreements.

Read the full study:

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.

References