Denial of benefits clauses (DoB) have gained considerable traction in the past prolific years of Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS), and more specifically, with the growing number of Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) arbitrations.

UNCTAD’s Investment Policy Hub still lists a considerably small number of international investment agreements (IIAs) providing for DoB: little above 200 which would account to less than 10% of IIAs. The ECT, in the current form of Article 17, provides for the following DoB:

Each Contracting Party reserves the right to deny the advantages of this Part to:

(1) a legal entity if citizens or nationals of a third state own or control such entity and if that entity has no substantial business activities in the Area of the Contracting Party in which it is organised; or

(2) an Investment, if the denying Contracting Party establishes that such Investment is an Investment of an Investor of a third state with or as to which the denying Contracting Party:

(a) does not maintain a diplomatic relationship; or

(b) adopts or maintains measures that:

(i) prohibit transactions with Investors of that state; or

(ii) would be violated or circumvented if the benefits of this Part were accorded to Investors of that state or to their Investments.

The situation referred to in paragraph 2 is still to be tested in practice (although with the increase concerns of economic sanctions, the matter is very much open). Paragraph 1 has been more frequently invoked.

It is understood that the purpose of DoB clauses like that in Article 17 of the ECT is to exclude investors and their investments from the protection of the IIA, even if formally satisfying the definition of investor, when not having a real (economic) connection with the home State. As such, DoB is not only a guarantee against the abuse of rights, but also a safety measure for safeguarding the integrity of the principle of reciprocity embodied in investment treaties.

In one of the decisions regarding the modernisation of the ECT, the Energy Charter Secretariat included the following note with regard to the DoB: “some IIAs specify that the denial of benefits clause can also be invoked once Investment proceedings have started”. The DoB is therefore on the radar of the reform process, with several issues being identified in the application of Article 17 of the ECT that may warrant amendment. These include the procedural aspects for invoking a DoB before arbitral tribunals, and issues pertaining to the substantive requirements under Article 17 (or ratione materiae, as referred to by the Waste Management arbitral tribunal).

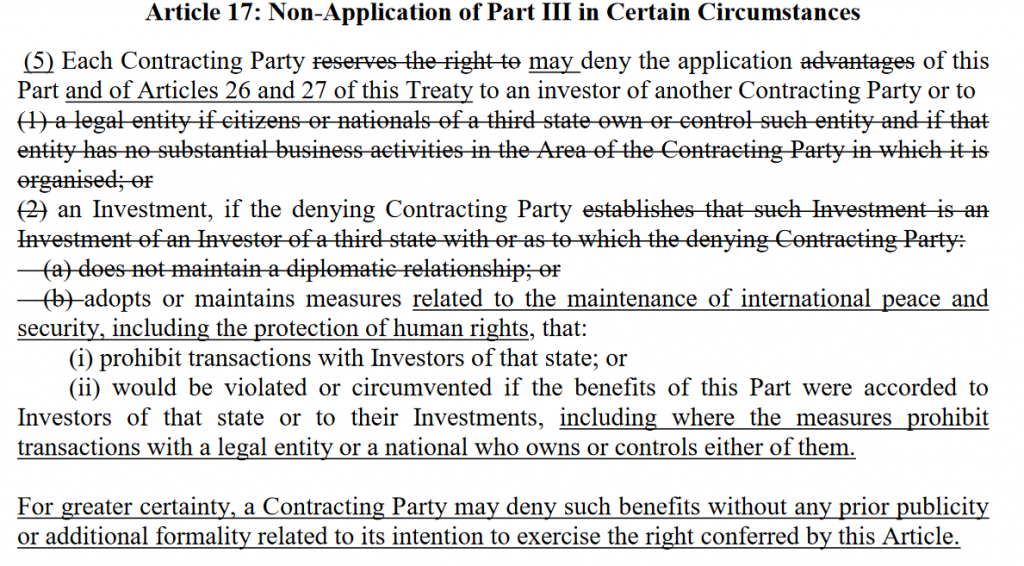

While discussions are conducted in the ECT Subgroup on Modernisation, there is little transparency on the progress of the modernisation process. On 27 May 2020, the EU published the proposed amendments to the ECT provisions, including those concerning Article 17 on the DoB. The proposed text appears to include solutions to the issues raised before ECT arbitral tribunals so far and also align the DoB with the recent IIAs concluded by the EU (for example, Art. 8.16 of the CETA):

It is also noteworthy that the paragraph 1 situation (substantial business activity in the Contracting Party) is a matter addressed in recent EU IIAs as a matter of jurisdiction and also reflected as such in the EU proposal through the amendment of Article 1(7)(a)(ii) of the ECT.

In light of the Energy Secretariat and EU proposals, and for the limited purpose of this post, two matters will be addressed: (1) the exercise of the right to deny the benefits of the ECT; and (2) the time when the respondent Contracting Party to the ECT should deny the benefits of the ECT. The brief analysis below reveals that the proposals for the amendment of Article 17 of the ECT are triggered by the evolving practice of arbitral tribunals with respect to DoB. In other words, the proposed new treaty text is aimed at reflecting arbitration practice. This is not an unusual approach, but a natural evolution of any system. For ISDS, this is not novel: ICSID, in its latest amendment process of the ICSID Arbitration Rules explicitly states in relation to various amendments that “the proposal streamlines the procedure in line with current practice”.

Exercising the denial of benefits right

The debate surrounding the existence of a DoB in an IIA first revolves around the question whether the denying State can benefit from the automatic application of the provision when the conditions spelled out in it are met or, to the contrary, if the State must exercise this denial right before the putative investor files its claim.

Article 17 of the ECT currently provides that ‘[e]ach Contracting Party reserves the right to deny’, as opposed to, for example, the corresponding provision in Article 8 of Iran-Slovakia BIT which states that ‘[t]he benefits of this Agreement shall be denied’.

As it stands, Article 17 of the ECT requires the denying Contracting Party to exercise the DoB ‘right’. In Plama v. Bulgaria, the arbitral tribunal took precisely this approach:

In the Tribunal’s view, the existence of a ‘right’ is distinct from the exercise of that right. … The language of Article 17(1) is unambiguous; and that meaning is consistent with the different state practices of the ECT’s Contracting States under different bilateral investment treaties … (para 155).

The arbitral tribunal in Khan Resources v. Mongolia, in holding that the ‘denial of benefits’ right must be exercised by the denying State, put forward a more incisive approach to this matter:

Article 17(1) of the ECT provides that the Contracting Party ‘reserves the right’ to deny the benefits of Part III of the ECT. The ordinary meaning of the verb ‘to reserve’ suggests that the right to deny the benefits of the Treaty is being kept by the Contracting Party, to be exercised in the future. … The interpretation that Article 17 requires an active exercise of the Contracting Party’s right to deny the benefits of Part III of the ECT is in line with the Treaty’s object and purpose (paras 419 and 421).

After establishing that the ‘denial of benefits’ right must be actively exercised by the respondent State, ECT arbitral tribunals embark on assessing the proper manner in which such exercise should be effected. Some IIAs require a prior notification and/or consultation procedure between the parties to the applicable IIA before effectively denying the benefits of that treaty to the putative investors. One such example is the now defunct Article 1113 of NAFTA. The ECT does not provide for such preliminary step.

In Plama v. Bulgaria, the tribunal considered that the exercise of the DoB “would necessarily be associated with publicity or other notice so as to become reasonably available to investors and their advisers” (para 157). As further explained by the Plama tribunal, “[b]y itself, Article 17(1) ECT is at best only half a notice; without further reasonable notice of its exercise by the host state, its terms tell the investor little; and for all practical purposes, something more is needed” (para 157).

As to prior notification, under the current Article 17 of the ECT arbitral tribunals are called upon to apply the DoB as it is. As the wording of the provision does not lead to the conclusion that the notification of investor is required and, furthermore, no time limits are associated with the exercise of the ‘denial of benefits’ right, arbitral tribunals should be cautious in reading such prerequisites into this clause. This is particularly so in light of Article 46 of the ECT, which provides that “[n]o reservations may be made to this Treaty”. One would also assess the opportunity of such a prior notice. In reality, in many instances host States become aware of investors and their particularities, and, more specifically, whether they fit into the ‘denial of benefits’ situation, at the time they are served with the request for arbitration. The proposal of the EU appears to identify the issue of a prior notification and suggest that the wording of Article 17 should be clear in that no “prior publicity or additional formality related to its intention to exercise” the DoB is required. Clear treaty language is certainly to be encouraged, in particular in the context of the concerns with consistency, coherence, predictability of ISDS.

When should a State exercise its denial of benefits right?

The surveyed ISDS case law shows that respondent States rely on DoB and effectively deny the benefits of the applicable IIA when a dispute is well underway, and more specifically, after the host State becomes aware of the request for arbitration submitted under the investor-state dispute settlement provisions. From a practical point of view, unless foreign investments have to be authorized by the host State, few denying States will become aware of the case before the submission of arbitral proceedings takes place.

In Ascom v. Kazakhstan, the arbitral tribunal expressed the position that “Art. 17 ECT would only apply if a state invoked that provision to deny benefits to an investor before a dispute arose” (para 745).

The proposal from the Energy Charter Secretariat for the amendment of Article 17 of the ECT suggests that a respondent Contracting Party could invoke the DoB even after the commencement of the ISDS proceedings under the ECT. This appears to be more in line with the conclusion of non-ECT arbitral tribunals dealing with DoB. For example, in EMELEC v. Ecuador, the tribunal concluded that “Ecuador announced the denial of benefits to EMELEC at the proper stage of the proceedings, i.e. upon raising its objections on jurisdiction” (para 71). In Ulysseas v. Ecuador, under the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, the tribunal concluded that the respondent State raised the DoB in a timely manner:

The first question concerns whether there is a time-limit for the exercise by the State of the right to deny the BIT’s advantages. … According to the UNCITRAL Rules, a jurisdictional objection must be raised not later than in the statement of defence (Article 21(3)). By exercising the right to deny Claimant the BIT’s advantages in the Answer, Respondent has complied with the time limit prescribed by the UNCITRAL Rules. (para 172).

It is undisputed that DoB gained traction and prominence in the first arbitration cases under the ECT. The ECT modernisation process is well underway and, while more transparency would be welcomed, it appears to implement an immediate response to concerns raised in ECT arbitral proceedings concerning operation of DoB. However, DoB must not only be viewed in isolation, for at least three reasons. First, DoB provisions, given their similarity, would inevitably experience a cross-fertilization, in particular when it comes to their application by arbitral tribunals. Second, ultimately DOB clauses are treaty provisions and their interpretation and application is to be performed in accordance with international law, possibly without any tribunal activism nor by adopting a dynamic interpretation approach. Third, in the context of the ISDS reform, mainly conducted under the auspices of the UNCITRAL Working Group III, the ECT cannot remain in isolation and DoB appears to respond adequately to some of the concerns raised in this process.

To read our coverage of the ECT Modernisation process to date, click here.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.