Legend has it that in 1752, Benjamin Franklin flew a kite in a thunderstorm, with a house key dangling from the string, to attract lightning and store it in a Leyden jar.

Similarly, academics, policymakers, lawyers, and parties have for years sought to capture the answers to transcendent questions about investment arbitration. Which variants justifiably determine wins or losses? Which proceedings should be considered fair? How should costs be allocated? Which measures are sufficient to promote transparency or protect confidentiality? What are the primary drivers of delay? When and how should prior investment arbitration awards be treated as having precedential value?

As clear answers have proven elusive, arbitrators have become the lightning rod (another of Ben Franklin’s inventions) for disagreements about these questions. One obvious reason is that the arbitrators decide each of these issues in individual cases.

Another, perhaps more subtle, reason is that the parties choose the arbitrators who will decide their cases. Thus, when appointing arbitrators in an individual case, the parties seem to have the power, indirectly, to affect if not control the answers to these questions. But that perceived power can be elusive as appointing parties often have limited insights into individual arbitrators’ attitudes and practices on these issues.

Today, in investment arbitration, the two primary sources of information about arbitrators are: 1) individualized research in professional networks to collect feedback from those who have had recent experiences with relevant arbitrators, and 2) summaries of relevant aspects of prior investment awards involving the relevant arbitrators prepared by associates.

These processes are both analogue approaches in an increasingly digital world. These ad hoc methods are seriously out of sync with modern practices in corresponding national litigation.

In a 2020 study by ALM Intelligence and LexisNexis, 98% of US legal professionals surveyed confirmed that legal analytics about clients, counsel, and judges improve their firms’ knowledge, competitiveness, and efficiency. Meanwhile, 81% indicated such analytics were appreciated and encouraged by their commercial clients, whose companies are inevitably data-driven on the business side.

As Burford’s Jeffrey Commission and Giulia Previti have recently explained, such analytics are “even more relevant in the context of international arbitration, where the parties and counsel exert a greater degree of control over key features of the dispute resolution process.” Perhaps most importantly, legal analytics in international arbitration can provide meaningful insights about individual arbitrators’ track records on such all-important issues as case management and procedural rulings, previous patterns in outcomes and rates of recovery, use of prior arbitral awards and other authorities, approach to costs and interest rates, and duration of proceedings and deliberations.

Even when awards are publicly available, it is time-consuming to read and analyze applicable awards, and difficult if not impossible to distil key data that may reveal patterns otherwise hidden within the texts and as among different arbitrators.

In recent years, there have been efforts to transition international arbitration research from manual, text-driven practices into the age of technology and data analytics—law firms have developed resources to organize their internal data and some important data tools have come on the market.1)See Kluwer Arbitration Practice Plus, Dispute Resolution Data, Jus Mundi.

Now, Arbitrator Intelligence (AI) Investment Reports represent a major breakthrough heralding a new era of data analytics in international arbitration.

As previously noted in this blog, AI has created an online platform that enables hundreds of practitioners from around the world to exchange information on a confidential and anonymized basis. This feedback is not only collected, but it is also extensively analyzed and made available to arbitration users in the form of AI Reports on individual arbitrators. The result is a resource providing data-driven and aggregated first-hand insights about arbitrators, even when the arbitrations in which they sat remain secret.

AI is taking some of the most innovative methodologies and insights used by academics and policymakers to empirically assess trends in the field of investment arbitration, and applying them to individual arbitrators. We are also supplementing data collected from investment awards with evaluative insights from individual practitioners collected through our online platform.

The remainder of this Blog unveils selected data analytics on a sample AI Report on a real arbitrator—let’s call her or him “Arbitrator X”—who regularly sits in investment arbitrations. These analytics showcase the kinds of insights that will soon be available to parties and counsel on all investment arbitrators.

Analytics on Duration of the Proceedings

One of the most enduring debates in international arbitration—heightened by increasing client concerns about run-away costs and the arrival of third-party funders—is what variables affect the overall duration of proceedings? Does one particular arbitrator consistently sit in arbitrations that take longer than other comparable arbitrations? Does the use of bifurcation or trifurcation procedures correlate with arbitrations that are longer or shorter? Are delays added because arbitrators take too long to render awards? Does the presence of a dissenting arbitrator correspond with expediency or delay in rendering the final award?

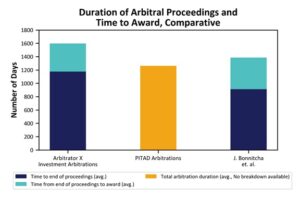

On the first question, a good way to understand an arbitrator’s track record is to compare their outcomes to other benchmarks, such as the average duration for all other similar arbitrations for which data is available.

AI Reports provide BOTH data regarding the overall duration of arbitrations from start to finish and (when available) data regarding the duration of deliberations and award drafting (i.e., the date of the close of proceedings, meaning date of final hearing or party submissions, to the rendering of the final award). Our reports often provide additional metrics (for example, median) in order to provide users with an insight into how outlier values impact the averages.

For Arbitrator X, the overall average duration seems longer, but only because there was one particularly drawn out case. Our Report explains that, when this unusual case is accounted for, this arbitrator actually has a relatively good track record on duration.

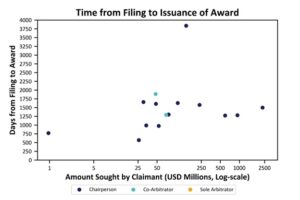

Apart from general benchmarking, our data examines the duration of an arbitrator’s cases based on the amount in dispute, on the assumption that the amount in dispute is a rough proxy for the complexity of the case.

The Figure also identifies cases in which Arbitrator X sat as a chairperson or as a party-appointed arbitrator. The assumption behind this analysis is that when serving as chairperson, an arbitrator may have greater control over proceedings. Thus, if arbitrations are more quickly resolved when a particular arbitrator is serving as chair, we might infer that they are efficient managers of proceedings.

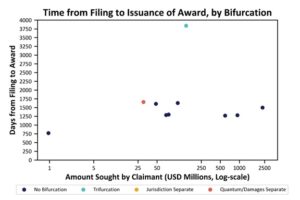

If the role of the arbitrator does not have a significant impact on duration, what about whether the arbitral proceedings are bifurcated or trifurcated?

In this Figure, Arbitrator X had only one known trifurcated case and only one bifurcated case, but those two arbitrations were among the longest. Benchmarking data in our Reports from all known investment arbitrations could provide a more nuanced perspective on these numbers.

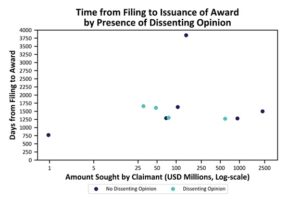

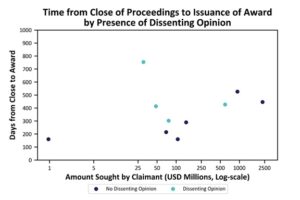

Another question sometimes raised regarding duration is whether the participation of a dissenting arbitrator correlates with arbitrations that take longer. One hypothesis might be that the presence of a dissenting arbitrator on a tribunal generally results in significantly longer proceedings. The assumption is that a dissenting award signals internal tribunal disagreements throughout the proceedings, and dissenting opinions may require longer deliberations and more extensive exchanges of drafts.

Let’s see what the data on Arbitrator X arbitrator says:

As it turns out, the data on Arbitrator X is inconsistent with the first hypothesis, but consistent with the second: There is no meaningful correlation between dissents and the overall length of proceedings,2)In other words, the differences are not statistically significant, particularly in light of the extremely small data set for one particular arbitrator. but there is a modest but measurable difference in the time for deliberations and award drafting.

It is somewhat surprising that award-drafting can take longer, but that increased time does not seem to have a corresponding impact on the length of the overall proceedings. It may be that Arbitrator X is conciliatory and effective at managing tribunal disagreements during proceedings or that disagreements only arose during the award-drafting stage.

Questions like these about what explains difference in the data require a brief note on methodology.

A Note on Methodology

These competing possible explanations for the data results reveal some important methodological issues regarding data analytics, particularly in the field of dispute resolution.

First, data can show correlation, but not causation.3)Even trained scholars sometimes mistake correlation for causation. See Catherine A. Rogers, The Politics of Investment Arbitrators, 12 Santa Clara Int’l L. Rev. 217, 226 (2013). Data can reveal correlations between one variable (the presence of dissenting opinions) and another (duration), but it cannot explain the reasons for that correlation. Additional analysis based on other variables (the role of the arbitrator on the tribunal, the industry or size of case, identity of other tribunal members, etc.) can illuminate the most likely causes.

Second, it is impossible to understand the true value of a data point without some comparative benchmark.4)This insight is one of AI-Friend Chris Drahozal’s favorite refrains. Christopher R. Drahozal, Arbitration Innumeracy, Y.B. ON ARB. & MEDIATION (forthcoming) (manuscript at 6). For example, 900 days may be outrageously long to a client that unreasonably expects even multi-billion-dollar cases to be resolved in a few months, but impressively efficient if compared with an average of more than 1250 in other investment cases. A 65% rate of recovery may seem meager until it is known that no Claimants received more than 90% of amounts requested, and less than 10% of parties received more than 50% of the amount requested. In our Reports, we benchmark both to publicly available data (such as from UNCTAD and published scholarly research) and to our own internal data.

Third, quantitative data is valuable on its own, but it is even more valuable when complemented by qualitative research.5)Gregory C. Sisk, The Quantitative Moment and the Qualitative Opportunity: Legal Studies of Judicial Decision Making, 93 CORNELL L. REV. 873, 877 (2008); see also Rogers, supra note 5, at 222 (arguing that empirical research about investment arbitration can be improved by “situate[ing] and supplement[ing it] with qualitative research and comparative institutional analysis regarding other international tribunals.”). Qualitative data, such as evaluative feedback from actual participants, can help us to better understand reasons for observed data. For example, through our online platform, we ask parties and counsel to indicate (for particularly long arbitrations) whether they thought the duration was reasonable in light of the size and complexity of the case or whether they know of any particular reasons for delay. This qualitative data is especially important for individual arbitrator data, which evaluates at best dozens of cases instead of the thousands of cases on which individual judicial analytics rely.

Other Topics for Analytics

In addition to timing, AI Reports provide analysis on issues such as methods for allocating costs between parties and rates at which parties were ordered to pay costs and lawyers’ fees.

Reports also include rates of recovery (not pictured) and a breakdown of outcomes on particular jurisdictional challenges and claims:

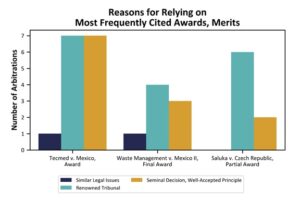

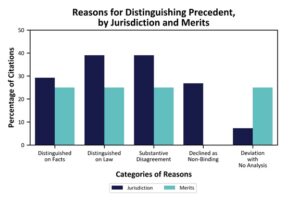

One of the most innovative and ambitious categories of data analytics in our Reports examines how tribunals treat prior arbitral awards. For example, we analyze, both with respect to jurisdiction and the merits, the reasons why Arbitrator X’s tribunals rely on or decline to rely on frequently cited prior awards.

Our Reports also include tables identifying all counsel, expert witnesses, and arbitrators from prior cases, and a host of analytics on other topics such as the appointment of tribunal secretaries, procedural rulings, questions asked by arbitrators during hearings, methods of interpretation adopted in awards, sources relied on (including prior non-investment awards and decisions), rates of recovery, costs, lawyers’ fees, and interest rates.

* * *

Soon you will be able to catch lightning in a bottle, and without risking electrocution.

Before the end of December, our Investment Reports will be available for individual purchase on a per-case basis. In the future, we will also offer other analytic tools that provide enhanced comparison of different arbitrators and that can identify arbitrators by characteristics identified in the data rather than by name.

The analytics in our Investment Arbitrator Reports will give users super-charged insights to assist with arbitrator research and selection, tribunal constitution, and case strategy.

Our Investment Arbitrator Reports are priced to reflect the extensive time and research that has gone into producing these exclusive insights. You can obtain significant discounts on that pricing, however, by becoming a Member of Arbitrator Intelligence. From now until the end of April, current and new subscribers to Kluwer Arbitration Practice Plus can also receive three free Reports and a discount on the non-Member price for additional Reports.

Membership is open to law firms, corporate and State parties, and third-party funders. And until the end of December, Membership is free of charge, but still entitles Members to special discounted Member-pricing.

In exchange for these benefits, Members commit to submitting feedback through our online platform at the end of each arbitration, providing both anonymized quantitative data on non-public awards and qualitative data to enable us to produce increasingly sophisticated and nuanced analytics.

To sign up for Membership, please contact info@arbitratorintelligence.com

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.

References

| ↑1 | See Kluwer Arbitration Practice Plus, Dispute Resolution Data, Jus Mundi. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | In other words, the differences are not statistically significant, particularly in light of the extremely small data set for one particular arbitrator. |

| ↑3 | Even trained scholars sometimes mistake correlation for causation. See Catherine A. Rogers, The Politics of Investment Arbitrators, 12 Santa Clara Int’l L. Rev. 217, 226 (2013). |

| ↑4 | This insight is one of AI-Friend Chris Drahozal’s favorite refrains. Christopher R. Drahozal, Arbitration Innumeracy, Y.B. ON ARB. & MEDIATION (forthcoming) (manuscript at 6). |

| ↑5 | Gregory C. Sisk, The Quantitative Moment and the Qualitative Opportunity: Legal Studies of Judicial Decision Making, 93 CORNELL L. REV. 873, 877 (2008); see also Rogers, supra note 5, at 222 (arguing that empirical research about investment arbitration can be improved by “situate[ing] and supplement[ing it] with qualitative research and comparative institutional analysis regarding other international tribunals.”). |