Social media are meant to facilitate connections. They make it possible to meet inspiring people from all over the world, especially now that we are subject to travel bans due to the protracted sanitary emergency. Connections are indeed a wonderful asset. However, as professionals involved in disputes, have we reflected thoroughly on how these connections could be perceived from an outside perspective? And how do we secure our virtual environment?

On 15 April 2021, the webinar “Arbitrators and their online identity: a double-edged sword” took place, jointly organised by the Madrid International Arbitration Center (MIAC), the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators Young Members Group (CIArb YMG), Arbitrator Intelligence, AMCHAM Quito and CyberArb. The event consisted of two panels: the first one, moderated by Sebastiano Nessi of Schellenberg Wittmer, featured a discussion on the potential risks faced by arbitrators in handling their online identities. The second panel, moderated by Wendy Gonzales of CyberArb, focused on practical tips to secure arbitrators’ online identity.

Can interactions on social media give rise to arbitrator challenges?

Following the year of the pandemic and of virtual hearings, LinkedIn has become the new conference room, with 700 billion users from 200 countries. Nowadays, arbitrators use LinkedIn as a powerful personal branding tool. However, Michele Potestà of Lévy Kaufmann-Kohler warned against the overwhelming flow of updates celebrating others’ achievements which could put unnecessary pressure on those who view them and make those people lose sight of their own goals, especially at early stages of their career.

As known, the IBA Guidelines on Conflicts of Interest in International Arbitration consider doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality or independence as ‘justifiable’ on an objective basis. Could social media connections give rise to conflicts of interest and consequent challenges? Yasmin Lahlou of Chaffetz Lindsey recalled that contacts with other professionals through a social media network are expressly included in the Green List (at article 4.3.1) and thus do not need to be disclosed and noted that no challenge brought on such basis has been successful yet.

It was then asked whether the different types of reactions available for LinkedIn posts which go beyond a simple ‘like’ – i.e. ‘celebrate’, ‘support’ , ‘insightful’, ‘curious’ and their different interpretation in foreign languages – may reflect different degrees of intensity in the relationship between the involved users. A reasonable doubt could arise whether the reaction was towards the content of the post or rather towards its author. The panellists unanimously agreed that while proceedings are pending arbitrators should avoid interacting with stakeholders involved. However, the panellists disagreed on the degree of self-restraint: while Niuscha Bassiri of Hanotiau & van den Berg suggested filtering through the connections and removing the parties’ counsels and even their law firms, Potestà considered that excessive. Lahlou observed that caution reflects deep comprehension of the issue and that it should therefore be practiced until a standard is set by the courts.

Ultimately, social media connections and interactions are not the problem per se, but they could become problematic if they constitute evidence of underlying substantial and close relationships between the arbitrator and other professionals. When in doubt, disclosing such close relationships is the best way to avoid subsequent challenges.

How far does the parties’ duty to investigate go?

When carrying out due diligence on potential arbitrators, parties’ counsels are now expected to explore their background on social media – Bassiri drew a parallel with due diligence conducted by human resources when hiring someone. Particularly, LinkedIn makes a user’s connections plainly visible. In contrast, it would not normally be expected of counsels to do extensive research on Twitter, because arbitrators normally do not use and abuse that platform by continuously posting materials. Things might change, however, following the recent Sun Yang case.

How can arbitrators secure their online identities?

As a greater part of our personal and professional lives moved online, so did the security risks. In fact, every 11 seconds a cyber-attack occurs. It is therefore paramount for arbitrators to secure their online identity. Thus, the second panel offered three practical tips, bearing in mind that the list is not exhaustive.

First, secure your network. Social media connections can compromise the security of one’s network when coming from fake accounts. Once connected and masqueraded as trusted profiles, they could launch phishing attacks, i.e. send malicious links or documents through e-mail or instant messaging services that are also available within social media.

Thus, when receiving hyperlinks or attachments from connections we are unsure about, Sophie Nappert of 3 Verulam Building recommended avoiding clicking on them and double-checking using ‘old-fashioned’ methods, such as directly calling the sender, to make sure that there is a real and trusted person on the other side. Furthermore, Catherine Rogers of Arbitrator Intelligence noted that connections can be used as guerrilla tactics, when parties’ counsels or agents make an attempt at connecting with the appointed arbitrator and engage him or her in those which could be perceived as ex parte communications.

Nonetheless, Kabir Duggal of Columbia University acknowledged the benefits of using social media and suggested that most problems could be avoided simply by using common sense. He noted that challenges can always be raised, yet parties need to make sure to ‘shoot to kill’ and common sense could serve as a robust shield against the bullet.

Second, secure your tools. It is becoming a common practice in virtual settings that arbitration stakeholders utilise instant messaging tools to exchange confidential arbitration related content, especially for quick communications during virtual hearings. WhatsApp is the undisputed big player in the field, yet even though WhatsApp features end-to-end encryption, it is questionable how suitable WhatsApp is for confidential proceedings, including arbitration proceedings. Duggal explained that some arbitrators prefer to use such external tools due to the high chances of making mistakes when using the chat box within Zoom or other video conference platforms, especially when dealing with high-intensity, crowded, proceedings.

Third, secure your content. Rogers remarked that social media platforms are owned by companies that systematically profile their users for commercial purposes. Parties to an arbitration are aware that information is all over the place, given the plethora of online platforms available and, due to the lack of information publicly available on arbitrators, there may be efforts to use their online activity to profile them in order to predict their behaviour. She also warned that the audience on social media is not limited to one’s connections. The content one shares can be re-shared and reach a potentially unlimited public, and even deleted content can still be accessible. This is the kind of personal scrutiny everyone should get used to.

Conclusions

More challenges based on ‘justifiable doubts’ as to the impartiality and independence of the arbitrator are expected to be brought based on the arbitrators’ connections and activity online. The lack of guidance on the matter could be troublesome, yet any dedicated soft law might not have sharp teeth, due to the infinite number of variables in the context of online interactions.

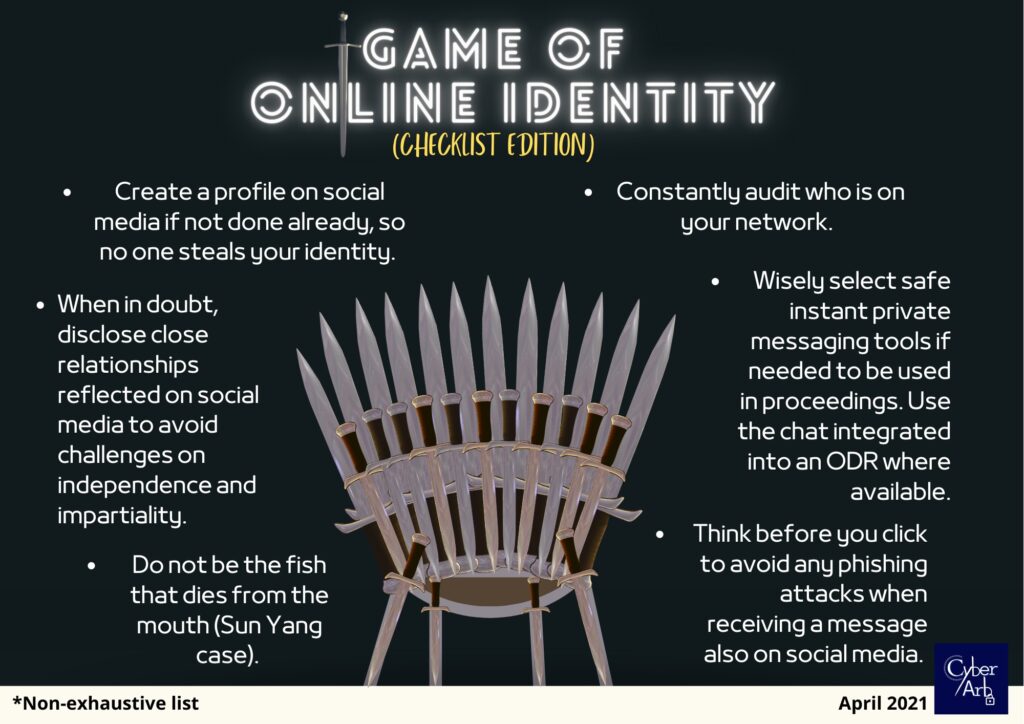

Arbitrators’ online identities must be handled pondering every click with common sense. Letting someone connecting to your network is no different than letting him or her inside your house. Arbitrators need greater awareness about cyber-risks and should not settle for unsafe tools just because they are familiar. Meanwhile, online dispute resolution (ODR) platforms are encouraged to develop and provide safer and more user-friendly integrated instant messaging functions for arbitration related communications. As aptly stated in the ICCA-NYC Bar-CPR Cybersecurity Protocol for International Arbitration (2020), cybersecurity requires effort from all stakeholders. Currently, ongoing initiatives aiming to bridge the gap between theory and practice might be of help.

To sum up, online identities can potentially become a double-edged sword, and — similar to a certain TV series — this could determine the fate of attempts to control the mysterious land of Westeros or, analogically, social media.

=======

Further posts on our Arbitration Tech Toolbox series can be found here.

The content of this post is intended as educational and general information only. It is not intended for any promotional purposes. Kluwer Arbitration Blog, the Editorial Board, and this post’s authors make no representation or warranty of any kind, express or implied, regarding the accuracy or completeness of any information in this post.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.