The results of the 2021 QMUL-White & Case International Arbitration Survey were launched on 6 May 2021. The survey explores the theme of “Adapting Arbitration to a Changing World”: how international arbitration has adapted to changing demands and circumstances including the COVID-19 pandemic, and opportunities for the international arbitration community to adapt more and better. This is the 5th survey conducted by the School of International Arbitration, Queen Mary University of London, in partnership with White & Case. This blog focusses on adaptations to arbitral rules and by institutions; subsequent blogs will address other key topics from the survey.

A hallmark of international arbitration is its flexibility to develop and adapt in response to the changing needs of its users. The evolution of arbitration rules, both ad hoc and institutional, is an important mechanism to achieve that flexibility. The 2021 Survey revealed the ways in which drivers of change such as diversity and technology, coupled with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, have already been reflected in, and will continue to influence the development of, innovations in procedural rules.

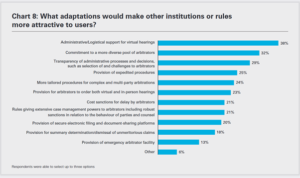

This year’s survey confirmed a trend that we observed in our 2015 and 2018 QMUL-White & Case International Arbitration Surveys: when it comes to choice of procedural frameworks, whether provided by arbitral institutions or under ad hoc regimes, arbitration users appreciate a wide degree of choice but also tend to pick those they already consider to be ‘tried and tested’ options. We therefore asked respondents what adaptations would make other arbitral institutions or sets of arbitration rules more attractive to them.

Respondents were asked to choose up to three options from a list of indicative choices, as well as a free-text ‘other’ option. Some suggested adaptations related to provisions in arbitral rules, while others concerned the service offered by arbitral institutions and appointing or administering authorities. The responses signal changes in the nature and extent of the services that users would like administering entities and arbitral institutions to offer.

The top choice (selected by 38% of the total respondent pool and 32% of in-house counsel) was “administrative/logistical support for virtual hearings”, and 23% of users selected the related request for “provision for arbitrators to order both virtual and in-person hearings.” These results clearly reflect the need for arbitral practice to adapt to the challenges posed by the pandemic to holding hearings in-person, and the respondents’ call for the arbitral institutions to support that change.

Most arbitral institutions have not traditionally offered administrative support for virtual hearings per se. At the global launch event for the 2021 survey results, Dr Jacomijn van Haersolte-van Hof, Director General of the LCIA, explained that from the perspective of arbitral institutions, their role has been facilitative, ensuring that there is a rules framework that accommodates the practical conduct of arbitrations including, where appropriate or necessary, the use of virtual hearings and electronic communications.

White & Case partner Dipen Sabharwal QC, speaking at the same event, concurred that the provision of the physical infrastructure to conduct arbitrations, particularly hearings, has typically been the domain of third party providers rather than institutions. He noted that the switch to virtual settings should not necessarily change that. However, he also pointed out that history shows the adaptability of arbitral institutions and other rules providers in response to needs articulated by arbitration users. For example, the lowest ranking adaptations selected by respondents were “provision for summary determination/dismissal of unmeritorious claims” (18%) and “provision of emergency arbitrator facility” (13%). In our previous surveys, respondents expressed interest in having these procedural mechanisms available to them.1) See, e.g., 2015 QMUL-W&C International Arbitration Survey, Chart 25: 93% of respondents favoured the inclusion of emergency arbitrator provisions in procedural rules. Many widely used sets of arbitration rules now include these features. Mr Sabharwal suggested that those mechanisms were given lower priority by the respondents to the 2021 survey precisely because the market of institutions and rules providers have already responded to user demands for these adaptations. As Mr Sabharwal reflected, in light of both the wishes expressed by respondents to our 2021 survey and the historic trend he identified, arbitral institutions may start to provide some degree of practical support for virtual hearings.

An area in which many institutions and other rules providers have already started to adapt is the “provision of secure electronic filing and document sharing platforms” (chosen by 20% of respondents). The Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce (SCC), for example, offers a secure digital platform for communications and file sharing between the parties and the tribunals in both SCC and, since May 2020, ad hoc arbitrations. Many institutions and administering bodies also provide electronic filing systems.

Dr van Haersolte-van Hof highlighted the swift response of institutions which have updated their rules, or are in the process of doing so, to accommodate changes that reflect the “new normal” brought about by the impact of the pandemic. She noted that the LCIA had been poised to launch updated rules in March 2020, but chose to delay their introduction in order to make further amendments to better reflect the change in circumstances. For example, a provision was inserted in the 2020 LCIA Rules to expressly allow for awards to be signed electronically (Article 26.2), and electronic means of communications are now the default (Article 4). She described the development across the arbitration community, and rules providers in particular, of a “consensus and acceptance” of new practices. The changes being implemented to procedural rules by providers in reflection of this consensus will, in her view, “be an important building block for allowing hearing centres and individual tribunals to accommodate new styles.”

Dr van Haersolte-van Hof also considered the link between the provision of electronic filing and document sharing platforms and responsibility for information security. In response to a question on cybersecurity measures, 40% of respondents thought “platforms or technologies provided or controlled by the arbitral institution” should be used. 41% also welcomed guidance or protocols from institutions.

Dr van Haersolte-van Hof agreed that the need to deal with cybersecurity becomes all the more essential as practices become increasingly digitalised. However, she cautioned that it is difficult to say how much institutions can or should provide these services. As with the consensus that has been reached in terms of facilitating changes resulting from the impact of the pandemic, she encouraged the arbitration community to do more to come to a consensus about what is needed and what standards should be applied. In this regard, she stressed the need to bear in mind the great diversity across users of international arbitration and their differing preferences and financial positions.

In our 2018 survey, 80% of respondents identified arbitral institutions, and 56% named “arbitration interest groups/bodies” as the stakeholders who are best placed to influence the evolution of international arbitration.2)2018 QMUL-W&C International Arbitration Survey, Chart 39. The results of the 2021 survey and the history of adaptations of procedural rules confirm the role of rules providers in both reflecting and influencing change.

Any views expressed in this publication are strictly those of the authors and should not be attributed in any way to White & Case LLP.

White & Case means the international legal practice comprising White & Case LLP, a New York State registered limited liability partnership, White & Case LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated under English law and all other affiliated partnerships, companies and entities.

This article is prepared for the general information of interested persons. It is not, and does not attempt to be, comprehensive in nature. Due to the general nature of its content, it should not be regarded as legal advice.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.

References

Many thanks for this. Looking forward to your subsequent entries.

m.

What adaptations would make other arbitral institutions or sets of arbitration rules more attractive to them?

This gave me a great idea for a parlour game.

So the members of staff of the arbitral institution, except one, stand in a big circle facing inwards.

The person who’s cast out at the beginning plays the role of “The User”.

Play begins when one person in the circle says the words “It’s good to know…” followed by a rule or an adaptation of a rule which is thought to make the institution attractive.

For example, “It’s good to know that our rules provide for summary determination.”

If The User is impressed, then he/she pats the speaker on the back and it is the turn of the next person in the circle to say “It’s good to know…”

If, however, The User is unimpressed, he/she may ask “What’s in it for me?” and then the speaker must elaborate.

For example, someone might say, “It’s good to know that from our perspective our role has been facilitative,” then The User would be able to ask, “What’s in it for me?”, and the speaker might answer, “Well, we provide a rules framework that accommodates the practical conduct of arbitrations including, where appropriate or necessary, the use of virtual hearings and electronic communications.”

If The User is still unimpressed, then that speaker is out and becomes The Signatory (of the institution’s rules). From then on, every speaker must get either pats on the back from the ones who are out or answer no more than one “What’s In It For Me” question, if any. The next person out becomes The Potential Signatory. The next person out becomes The Funder etc., or whatever other challenging categories of stakeholder you can imagine.

Anyone who hesitates for more than three seconds or laughs while speaking is out. The winner is the last person remaining in the inner circle.

Best played while watched by a large audience. Any dispute as to who’s out may be checked the following day against the survey. Warning: Game may not work as intended in some regions.