In the absence of concrete publicly available information about arbitrators, arbitration practitioners often resort to cognitive shortcuts and just plain guesswork in the arbitrator selection process. As explored in a previous post, parties and counsel frequently rely on arbitrators’ common-law or civil-law education and practice as indicators for how they might approach key case management issues. With the increasing complexity of international business transactions and the practice of international arbitration, such proxy indicators are no longer a reliable point of reference.

Given the need to access arbitrators’ approaches on various issues, Arbitrator Intelligence recently launched the Arbitrator Perspectives Survey (the Survey). The Survey invites arbitrators to answer many of the questions parties and counsel wish they could ask in an interview (and try to find out through indirect research with people who know the arbitrator). Systematic collection of this information directly from arbitrators reduces the risk that parties will have to roll the dice in arbitrator selection—now they can learn about arbitrators’ approaches directly from the arbitrators.

The questions in the Survey are carefully framed to make clear that arbitrators are not promising any particular ruling or stating an intransigent commitment to a particular view. The Survey confirms that any views are subject to the conditions and law applicable in a particular case. Finally, arbitrator responses are free on Arbitrator Intelligence’s website, but its use policies preclude use of Survey responses to challenge arbitrators.

Since the Survey’s launch in January 2022, Arbitrator Intelligence has collected perspectives from arbitrators with various levels of experience from 39 nationalities and based in 31 jurisdictions.

On 24 March 2022, Arbitrator Intelligence invited KAB readers to predict how arbitrators responded to various questions in the Survey. This post analyses how well KAB readers were able to foresee the Survey Responses collected from arbitrators as of 24 March 2022 (Surveyed Arbitrators). We also comment on some surprises we found among arbitrators’ responses.

What considerations are most important to co-arbitrators when selecting a chairperson?

Whatever considerations parties and counsel apply to the selection of party-appointed arbitrators, their selection of the chairperson can be even more complicated and consequential. Importantly, this decision is no longer exclusively in the hands of a single party, and often it is in the hands of the party-appointed arbitrators. In such circumstances, different considerations come into play.

Critics of international arbitration have suggested that co-arbitrators are most focused on appointing someone they know personally. Surveyed Arbitrators, however, most frequently identified seeking someone with a reputation for being efficient and being collaborative (or good at managing conflicts on the tribunal) as their key consideration. Most KAB Readers correctly anticipated that a reputation for being collaborative and/or good at managing conflicts within the tribunal was the key consideration for the selection of the chairperson. We found it surprising that—contrary to frequent critiques—arbitrators did not list personal familiarity with a prospective chair as one of the most important considerations.

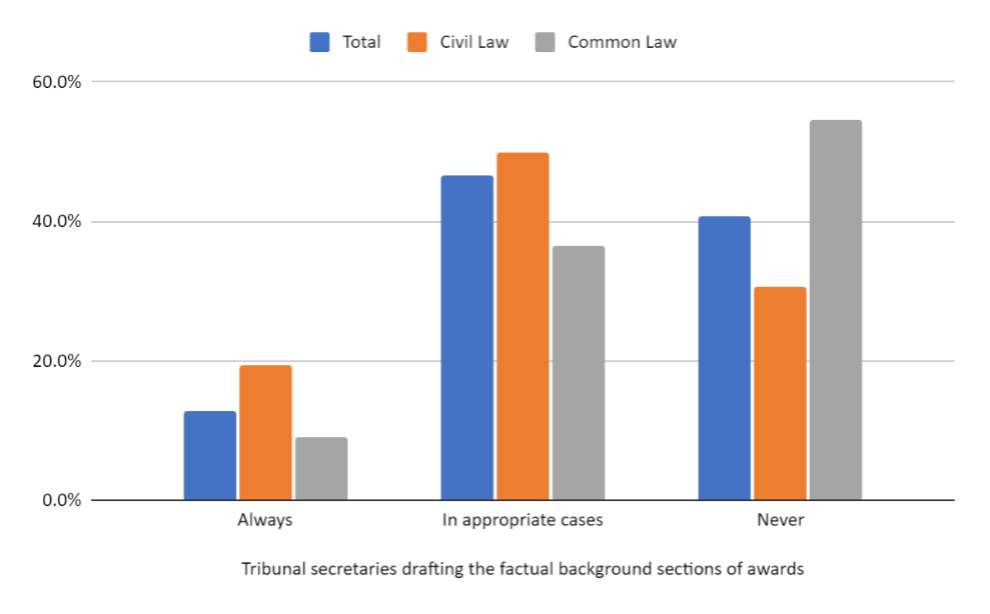

Do arbitrators consider it inappropriate for tribunal secretaries to draft the factual background section of an award?

In recent years, there has been increasing scrutiny of the role of tribunal secretaries in arbitral proceedings, with a special focus on the extent to which they should be involved in the drafting of awards. Critics are particularly concerned that arbitrators may be over-delegating and giving a decision-making role to tribunal secretaries. There are a few prominent examples of awards being challenged due to allegedly improper use of tribunal secretaries.

The expectation of the KAB Readers was that less than 25% of Surveyed Arbitrators would consider it inappropriate to allow tribunal secretaries to draft the factual background of the award. However, the reality is that 41% of the Surveyed Arbitrators considered such a practice inappropriate (31% of all civil law-trained and 55% of all common law trained arbitrators surveyed), 47% considered it appropriate in some cases and 13% considered it always appropriate.

Are arbitrators with a civil law or common law background more likely to consider it appropriate for arbitral tribunals to encourage and/or facilitate amicable settlement?

The question of whether arbitrators should encourage or facilitate amicable settlement between disputing parties is hotly contested, with strong views on both sides. Most KAB Readers expressed the view that civil law arbitrators are more likely to consider it appropriate to encourage and/or facilitate amicable settlement. However, when asked if it is generally appropriate for arbitrators to encourage and/or facilitate amicable settlement, 10% said no, 30% said yes, but 40% indicated it is appropriate only if the parties agree. There was not a significant difference in the positions of civil law and common law arbitrators in this regard.

If you are looking for an arbitrator who is inclined to facilitate settlement, you can look up individual arbitrators’ approaches in their own Survey Responses by going to our website.

What are the three most popular techniques for maintaining efficiency in arbitral proceedings?

In recent years there has been a proliferation of innovative rules (both institutional and others) that are aimed at reducing inefficiencies and streamlining the arbitral process. Many of them empower arbitrators to take more control over the proceedings to avoid unnecessary delays, while ensuring that the parties’ due process rights are respected. As this is a difficult balance to maintain, the Surveyed Arbitrators highlighted myriad case management tools they use to ensure efficiency in arbitral proceedings.

A reasonable expectation, and the primary expectation of KAB Readers, is that the most frequently used mechanisms would include limiting the number or scope of party submissions and requiring the early resolution of certain issues. However, the top three mechanisms selected by the Surveyed Arbitrators are: 1) case management hearings, 2) online hearings when appropriate, and 3) establishing and sticking to strict timetables.

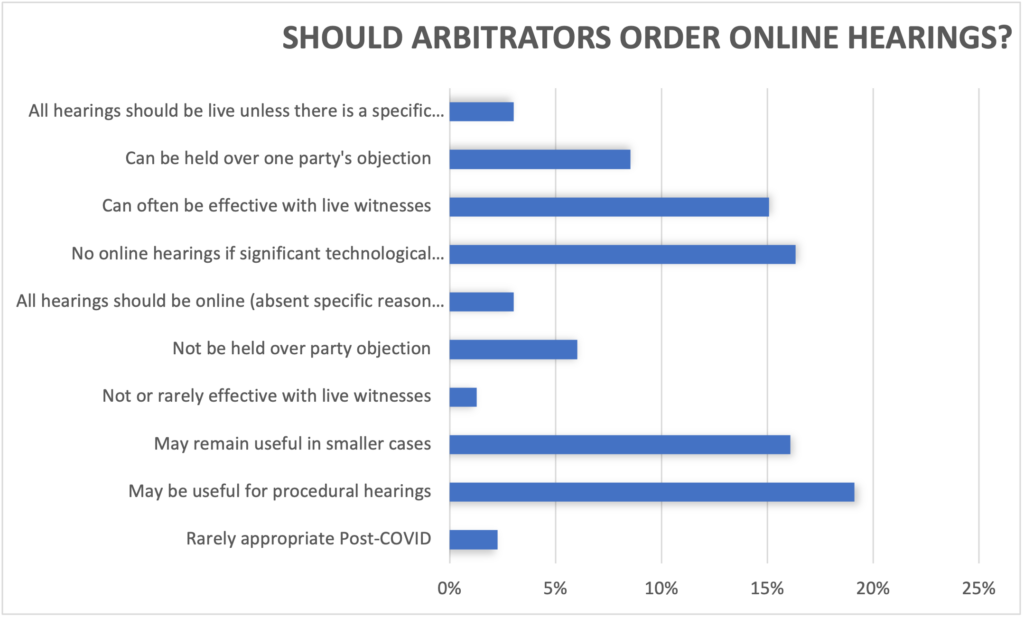

Given the popularity of online hearings, the Survey also asks about arbitrators’ views regarding online hearings.

If you are focused on efficient proceedings, it can be important to understand an arbitrator’s view about online hearings before appointing them. In addition to arbitrators’ Survey responses, Arbitrator Intelligence Reports also provide numerous examples of procedural rulings and parties’ and counsel’s assessments of tribunal efficiency in specific past cases. For example, wouldn’t you like to know which arbitrator uses a chess clock to keep hearings running smoothly?

What percentage of surveyed arbitrators would be inclined, when otherwise appropriate, to order online hearings despite one party’s objection?

Online or remote hearings have become a daily reality in international arbitration, and they are recognized as a viable option under the national arbitration laws of most jurisdictions worldwide. However, there are still open questions about the extent to which arbitrators can order and conduct online hearings against the objection of one of the parties. Although arbitrators enjoy broad discretion to design and conduct arbitral proceedings in the interest of efficiency and effectiveness, concerns about the ability of both parties to present their case and the enforceability of arbitral awards abound. The perception of most KAB Readers was that less than 20% of arbitrators would hold online hearings, when otherwise appropriate, over the objection of one of the parties. Instead, 37% of all Surveyed Arbitrators consider such practices appropriate.

Although not displayed in the above table, there was also a significant difference in the perspectives of arbitrators from different backgrounds. Arbitrators with common law backgrounds are considerably more inclined to hold online hearings over party objection than arbitrators with civil law backgrounds (52% versus 35% respectively).

Even more interesting than the numbers were differences in some of the arbitrators’ stated views on the subject based on their past experiences. One arbitrator stated that “Online hearings cut the human side of the process, on all sides (parties, arbitrators); their overuse are therefore dangerous.” Another arbitrator instead believes that “The covid era has proved beyond doubt that online hearings can be effective even with live witnesses.”

Many expressed the need for individual case-by-case assessment, with several expressing what they have learned from experiences with online hearings, such as the need for breaks and coordination of different time zones. One arbitrator offered an interesting view about their value: “The adequacy [of an] online hearing does not depend on the value of the case, but on the complexity of the evidence to be produced.”

Do arbitrators with civil law backgrounds have views about e-discovery that differ from arbitrators with common law backgrounds?

The issue of document production in international arbitration, and e-discovery in particular, is widely perceived as the paradigmatic distinction between arbitrators with common law and civil law backgrounds. The traditional view is that arbitrators with civil law backgrounds are much less likely to order e-discovery than their common law counterparts.

Contrary to this traditional view, KAB readers estimated that 50% of arbitrators would be willing to grant e-discovery, with slightly more support from common law arbitrators. However, only 38% of Surveyed Arbitrators overall considered e-discovery generally appropriate in relevant cases. Perhaps more surprisingly, there was not a significant divergence of positions between civil law and common law trained arbitrators.

Do arbitrators with civil-law backgrounds ever consider production of broad categories of documents based on general statements of materiality and relevance to be appropriate?

Closely related to the previous question, there are also deeply rooted perceptions that civil law trained arbitrators are very conservative when it comes to the scope of document production (when ordered) and that they would almost never grant broad discovery based on general statements of materiality. KAB Readers estimated that less than 10% of civil law arbitrators would be in favor of such document production.

This question is where perhaps the biggest surprise comes in data received so far from Surveyed Arbitrators: 45% of the Surveyed Arbitrators who have a civil-law background indicated that such document production could be appropriate in some circumstances, while 33% of them consider it “often appropriate.” Coming from a group of arbitrators of diverse nationalities, these responses show that generally held assumptions about civil law trained arbitrators are not necessarily accurate and that if you are looking either to find or avoid an arbitrator who will grant broad document production, you need to look further than their legal background.

Arbitrator Intelligence Reports, which are based on information from parties and counsel (not arbitrators), also provide details about the hows and whens of document production in prior cases, as well as specific assessments from the participants. Putting together specific past examples and arbitrators’ expressed views is the best way to understand what to expect when appointing an arbitrator.

What do arbitrators think about asking questions in hearings and interrupting parties with those questions?

The common perception is that whether arbitrators are inclined to ask questions in hearings is largely associated with their legal training and background. Civil law trained arbitrators are traditionally considered to be more restrained at hearings, while common law arbitrators are considered more likely to intervene with questions. KAB Readers estimated that as much as 30% of civil law trained arbitrators held the view that arbitrators should generally refrain from asking questions at the hearings.

It turns out, however, that hardly any arbitrators hold this view—only about 1% of all Surveyed Arbitrators believed that arbitrators should generally refrain from asking questions at hearings. Perhaps even more surprising, 68% of all Surveyed Arbitrators considered it appropriate for arbitrators to interrupt counsel presentations or witness testimony with questions.

Allocation of costs and fees

Like any other arbitration practitioners, arbitrators may come to the table with a particular view on the allocation of costs and fees between the parties. Debate continues over whether “costs follow the event” or each party should bear its own costs. As a result, arbitrators of all backgrounds are facing situations in which they must make adjustments to costs allocated based on a variety of factors.

When asked what may lead them to change from their ordinary approach to the allocation of costs and fees, Surveyed Arbitrators selected “compelling arguments based on party agreement” and (somewhat surprisingly) the approach in the seat of arbitration as the most likely factors to influence such decisions. KAB Readers rightly guessed the first reason, but like us, did not expect the approach of the seat to carry such weight.

If recovery of costs and fees is important in your next case, it would be helpful to know an arbitrator’s views on these topics. Information about individual arbitrators’ past rulings on issues of costs and fees in their past cases is also available in Arbitrator Intelligence Reports.

Given that alleged counsel misconduct can also be a basis for shifting costs, we asked arbitrators about that too. Most arbitrators identified consideration in allocating costs and fees to be an appropriate response, along with oral admonitions and negative inferences about the evidence. Interestingly, however, 10% were open to sanctions and nearly 20% to referral to national bar associations.

Arbitrators, Share YOUR Perspectives Today

The analysis of the data collected through the Arbitrator Perspectives Survey reflects the increasing diversity of backgrounds, affinities, and mindsets of international arbitrators. When juxtaposed against assumptions in the arbitration community, as expressed in the responses to the Arbitrator Perspectives Quiz, generalizations about arbitrators’ approaches to procedural issues and case management are often inaccurate.

Direct, independent, and systematic data collection and analysis is essential for parties and counsel to make informed decisions in the arbitrator selection process. The feedback about arbitrators from parties and counsel provided in Arbitrator Intelligence Reports and the arbitrators’ own views expressed in the Arbitrator Perspectives Survey offer unparalleled clarity and unique insights.

We would like to thank the KAB readers who took the Arbitrator Perspectives Quiz, providing the basis for this analysis of the perception of the arbitration community about international arbitrators. Arbitrators can continue to submit their Survey responses here, and their Responses will be made available for free on Arbitrator Intelligence’s website.

We hope to further expand the scope of available information that will provide meaningful insights for the all-important decision about which arbitrators to appoint.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.