The Russian aggression in Ukraine has not only brought immense human tragedy, but also unprecedented uncertainty upon the European energy markets. Gas supply has emerged as a particularly weak spot of the entire European economy, being massively overdependent on Russian supplies. When Russian President Vladimir Putin issued the infamous Presidential Decree No. 172 of 31 March, requiring payments for the delivery of gas to be made in Rubles (the “Ruble Decree”), the situation grew even more complex. Not only is the Russian demand contrary to the payment terms of existing Gas Supply Agreements (“GSAs”), but it is also at variance with EU sanctions. Securing continued gas flows from Russia may, hence, require buyers to square a circle.

In this post, we will attempt to untangle some of the legal issues buyers face at this critical time, the resolution of which may have implications beyond the gas sector.1) Zeiler Floyd Zadkovich recently hosted a public webinar, discussing some of the problems triggered by the Ruble Decree and the disputes it may create. Events are quickly unfolding as we write, with many European GSAs currently at a watershed moment: Whilst the Russian Gazprom Export has already halted supplies to Poland and Bulgaria in late April, and lately also to Finland, payment is due under many European contracts these days. At this turning point, we may see gas supply contracts – including the arbitration of disputes – evolve into an extended battlefield of economic warfare.

Sanctions and Countersanctions – the Russian “Ruble Decree”

In response to the Russian invasion of 24 February 2022, the EU introduced new economic sanctions against Russia, building on the existing framework established after the annexation of Crimea in 2014. To date, the EU has introduced five sanction packages, each addressing different segments of the Russian economy. None of these packages expressly targeted Russian natural gas supplies to Europe.

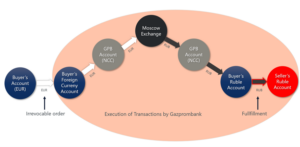

In reaction to these sanctions, Russia issued its own countersanctions. Of these, the Ruble Decree is probably the most notorious. To comply with the terms of the Ruble Decree, European buyers must open two special (conversion) bank accounts with Gazprombank JSC (“Gazprombank”), one denominated in the foreign currency designated in the GSA – i.e. Euros or US Dollars – and one in Rubles. To make payments under the GSA, buyers must first transfer the owed amounts to their foreign currency account with Gazprombank. This initial payment constitutes an irrevocable order to Gazprombank to convert the funds into Rubles, triggering a cascade of transactions whereby Gazprombank purchases Rubles at the Moscow Stock Exchange on behalf of the buyer, credits these Rubles to the second newly opened account of the buyer, and finally, credits the Rubles to the designated account of the seller. Importantly, the buyer’s payment obligation is only deemed fulfilled once this final transfer is completed.

If a buyer fails to comply with those terms, the Russian supplier Gazprom Export will be prohibited from delivering gas: such failure hence prompts an export ban. As can be seen above, the change in payment terms is beyond a mere technical shift, but extends the buyer’s risk sphere substantially.

The Ruble Decree caused a considerable stir among European leaders as well as key market players. The initial reactions ranged from complete refusal by the German chancellor to quick acceptance by the Hungarian president. Importantly, however, the Commission issued a statement, suggesting that compliance with the Ruble Decree would be in violation of the EU sanctions. This made the lives of the European importers even more difficult, adding the question of how to make payments in line with the Ruble Decree, whilst complying with EU sanctions.

Summary of EU Sanctions

Since the system of EU sanctions is quite intricate, for the purposes of this blog post we shall focus only on EU Regulation 833/2014 (“Regulation”). The Regulation contains a number of sectoral sanctions, among others, the prohibition of certain exports to Russia or the prohibition of any dealings with listed entities. Importantly, neither of the rules explicitly targets supplies of Russian natural gas as such.

Nevertheless, as a consequence of the Regulation’s general language, some sanctions now may as well affect natural gas supplies indirectly. For example, Art. 3a prohibits, among others, financing of any entity operating in the Russian energy sector. “Financing” is defined as any action whereby the entity concerned disburses its own funds or economic resources. The only exception to this definition is payment of the agreed price made “in line with normal business practice”. The sanction includes a carve out for gas supply, which, however, applies only for steps which are “strictly necessary”.

Other sanctions which could become relevant for gas supplies include the prohibition of engaging in certain financial transactions with listed Russian credit institutions under Art. 5. It is conceivable that the purchase of Rubles at the Moscow Exchange could be considered as such a transaction. Furthermore, sanctions in Art. 5a prohibit certain transactions with the Central Bank of Russia. Therefore, its involvement in the prescribed payment scheme could also lead to a breach of EU sanctions. With regard to this last point, the subsequent Decree No. 254 clarified that conversions – currently – do not involve the Russian Central Bank.

Also, the EU sanctions regime is new and untested, and there is only very little authoritative interpretation. Cases of violation would be addressed locally by authorities of individual EU members states, whose approaches may not be fully harmonized due to the lack of CJEU case law. Finally, the Regulation prohibits not only breaches of the individual sanctions, but also their circumvention. While the circumvention must be intentional, according to the CJEU, it is sufficient that the actor be aware that its participation may lead to circumvention and accept this possibility, making for a relatively low threshold.

Impact on Gas Supply Agreements

Evidently, all this puts EU importers of Russian gas in a difficult spot. In order to keep gas flowing, the Russian side demands full compliance with the Ruble Decree and as evidenced by Gazprom’s recent curtailment of supplies to Bulgaria, Poland and Finland, it appears poised to stay true to its word.

However, compliance with the Ruble Decree is fraught with serious risks for European buyers.

First, as discussed above, although the EU sanctions regime was not originally intended to target gas supply, the language of the relevant provisions is general and unclear. Therefore, the risk of committing a violation appears to be significant. Against this background, the EU Commission issued a guidance paper indicating that European buyers may open accounts with Gazprombank and pay in the designated currency on the first conversion account, as long as buyers declare unilaterally that they consider their payment obligation fulfilled with that first payment. This seems to offer a compromise, however, as of the date of writing, the Russian reaction to the procedure suggested by the Commission remains unknown. At the very least, the EU guidance paper makes it clear that plain abidance by the Ruble Decree would fall foul of EU sanctions.

Second, the payment mechanism provided for in the Ruble Decree significantly disrupts the risk allocation in European GSAs, not only by changing the agreed currency – invariably USD or EUR – but also by adding a third-party risk on the buyer’s side. As indicated above, the Ruble Decree stipulates that the payment obligation of the buyer is discharged only once Gazprom Export receives the Rubles in its account. Therefore, there is a gap of several days during when the buyers bear all risks that follow Gazprombank’s conversion and transmission of the sum, hence effectively acting as an agent for the buyer. It is unclear what would happen if the currency exchange was delayed or where the Russian government decided to seize the funds before the final Ruble payment is made, although the Russian Central Bank “explained” that payment irregularities caused by Gazprombank transactions should not lead to an export ban where the buyer had made timely payments “in good faith” and in compliance with the Ruble Decree. However, the official explanation contained an important caveat: Where conversion fails due to sanctions issued by unfriendly states, the export ban still applies. Therefore, overall, this falls short of addressing EU buyers’ concerns.

Also, while it may depend on the specific terms of an individual GSA, the Russian supplier will likely not be entitled to unilaterally impose the Ruble Decree payment scheme. This will hold particularly true where such GSAs are legally rooted in the jurisdiction of an “unfriendly state”, e.g. by choosing an EU, British or Swiss seat of arbitration and governing law.

It remains to be seen whether European efforts to allow buyers to “pay in Rubles without paying in Rubles” will suffice to keep the gas flowing. Given the volatility of this extraordinary situation and the stakes involved, arbitration lawyers may soon see a host of disputes come their way, a new wave of gas supply arbitrations, if you will: If the Russian side stops gas deliveries because payments made by European buyers in compliance with EU guidance would – despite all efforts – be deemed contrary to the Ruble Decree, would that be a breach of contract? Would it give rise to damages? What if, conversely, buyers refuse to comply with the Ruble Decree altogether? Would that give rise to any claims by Gazprom? All of these and many other questions will have to be addressed by arbitral tribunals, whose constitution may be particularly challenging these days.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.

References