The British Institute of International and Comparative Law (“BIICL”), and DLA Piper, recently organized an event titled Revised ICSID Arbitration Rules: Key Changes. Following the initial presentation of Martina Polasek (ICSID Secretariat), Prof. Yarik Kryvoi (BIICL), Kate Cervantes-Knox, (DLA Piper), Guglielmo Verdirame KC (Twenty Essex) and Dr. Anthony Sinclair (Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan) shared their insights on the new rules.

The amendment of the arbitration rules coincides with the intensified efforts to reform the system of investor-state dispute settlement to make it less expensive, more time efficient and fair for stakeholders. In this blog post, we discuss the major changes the panellists touched upon, such as: greater transparency; enhanced efficiency; the tribunal’s express powers to order security for costs; the regulation of third-party funding; or the opening of ICSID to other international actors, such as Regional Economic Integration Organizations (REIOs) like the European Union.

Arbitrators Must Actively Ensure Efficiency, Sometimes Even at the Cost of Flexibility

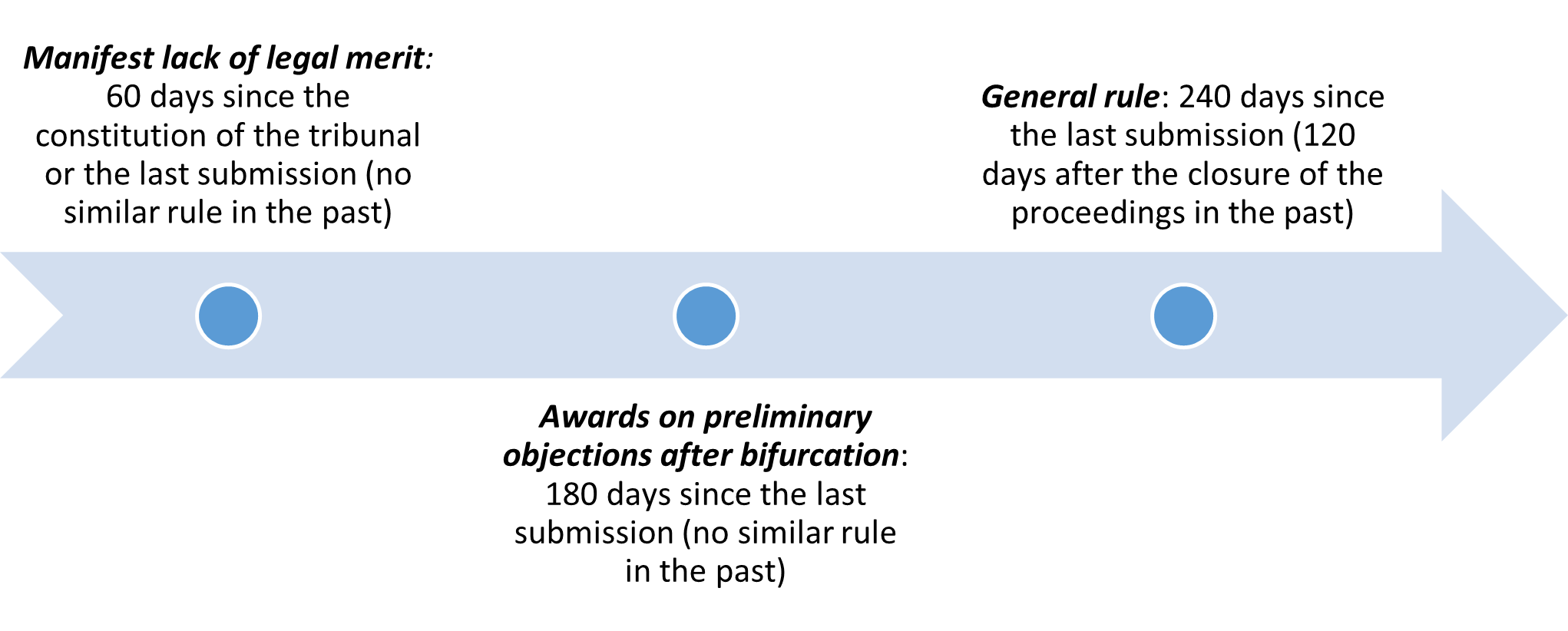

The 2022 ICSID Rules impose stricter deadlines upon the parties (see Figure 1), obligations on arbitrators to conduct at least one case-management conference, and other specific changes to achieve greater efficiency. These rules also include an express obligation on the parties to ICSID proceedings to act in good faith and to conduct themselves “in an expeditious and cost-effective manner”. Failure to do so may result in the tribunal allocating additional costs.

Critics of ISDS often point to the extensive duration of ICSID proceedings and their costs, which are recognised concerns by the UNCITRAL Working Group III. The 2022 ICSID Rules aim to tackle these concerns.

Figure 1. Timeframes to render an award (new time-limits on top of the figure)

These changes, however, may also have potential downsides. For instance, the panellists highlighted the risk that the new rules might force arbitrators “to act with a stick” to ensure procedural efficiency at the behest of flexibility. One panellist mentioned that, realistically speaking, these changes will primarily affect the most in-demand arbitrators, who may for instance, struggle to comply with strict time-limits. According to the newly introduced Rule 12, if the tribunal cannot comply with an applicable time limit, it shall advise the parties of the special circumstances justifying the delay and specifying the date when it anticipates rendering the expected decision.

The rules also introduce the possibility of dismissing claims based on the manifest lack of legal merit (Rule 41), which addresses the concern of frivolous claims brought by an investor to put financial and reputational pressure on the host state.

The new expedited arbitration procedure makes it possible for the parties to obtain an award in a little over a year upon the constitution of the tribunal. The idea is not only to decrease duration, but also to make it easier for small and medium-sized enterprises to start ICSID proceedings. However, as one of the panellists pointed out, parties – especially states – may view the possibility of expedited proceedings with caution. Another panellist noted, that States would unlikely commit to such proceedings without first seeing the claimant’s memorial and probably will not be in a rush to respond and commit to expedited proceedings given the need to find lawyers and go through relevant internal procedures.

The Tribunal Can Now Expressly Order Security for Costs

As pointed out by one of the panellists, an express provision on security for costs (Rule 53) brings much-needed clarity on the power of the tribunal to order security for costs, as the old version of the rules were unclear on that.

When faced with a request to order security for costs, the arbitral tribunal will look at the other party’s ability and willingness to comply with an adverse decision, how such a decision affects that party’s ability to further pursue its (counter) claim, and at the conduct of the parties. The rules mandate that the tribunal looks at all the relevant circumstances. As pointed out by one of the panellists, this may also mean considering the existence of a third-party funder.

The general rules on costs have become more detailed in the revised rules. The tribunal can now adopt an interim decision on costs, even on its own initiative. In addition, the new rules provide that the costs following the event should become the default approach of tribunals (Rule 52).

Third Party Funding Is Now Expressly Regulated – With a Catch

One of the major changes brought by the new rules concerns the express regulation of third-party funding (“TPF”). Many have called for this before, with the European Parliament recently voicing its concerns.

According to the 2022 Rules, a funded party must disclose in detail information of the funder, such as its name and address, and who controls it (in case of legal persons). While the panellists generally viewed this change as positive, they also expressed some criticism. One panellist pointed out that the broad language used in the Arbitration Rules makes it hard to know exactly when something qualifies as TPF or not. For instance, would a law firm acting on contingency fees qualify as a TPF?

Moreover, as pointed out on this blog before, the obligation to disclose the TPF agreement (when the arbitrators consider this necessary) might adversely affect the litigant’s procedural strategy. For instance, it might make it so that the disclosure of certain arguments and positions of parties become known earlier – or in a skewed manner – than those parties would have wanted. This, in turn, could affect the arbitrator’s view of the case.

The New Rules Open the ICSID Framework to More Actors

The amended Additional Facility Rules now permit their use even when neither the state is a party to the ICSID Convention, nor the investor comes from an ICSID contracting state. That means that the ICSID Additional Facility Rules will compete with UNCITRAL rules, which are also not linked to being a party to an international treaty.

Similarly, REIOs (such as the European Union) can now also use the Additional Facility Rules. This could become even more relevant in the future with REIOs concluding more international investment protection agreements and possibly finding themselves as respondents before arbitral tribunals. In the end, the changes are important given that the EU could most probably not have become an ICSID Convention party.

Conclusion

The ICSID Secretariat has concluded the significant task of modernizing its arbitration rules, which, after years of extensive consultations with key stakeholders and preliminary drafts, it shared with the public. These changes will help alleviate some concerns in relation to ISDS.

All the panellists agreed that if the new rules had been adopted earlier, a great number of investment disputes administered under the previous ICSID Arbitration Rules would have been conducted more efficiently. The potential shortcomings of the new rules will become apparent when arbitrators apply them in practice.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.