In 2011, the ITA published its inaugural Guide to Arbitral Institutions in Latin America and an accompanying “Scoreboard.” The conclusion of this inaugural guide was: “The era of Latin American arbitral institutions has arrived. Building on a strong legal framework, arbitral institutions have emerged throughout the region.”

This year, the Americas Initiative of the ITA published its 2023 edition. The 2023 Guide (the “Guide”) identified more than 170 arbitral institutions and presented various findings for 30 of these institutions in 20 different countries. The Guide surveyed several hot topics in international arbitration in addition to various topics that were covered in the 2011 edition, measuring the growth over the last decade. The Guide also included information on the relevant arbitral laws and treaties in each country, as well as their global doing business scores as reported by the World Bank. Finally, the Guide included links and information related to the relevant institutional rules for each institution. These were also included in the helpful “Scoreboard” that accompanied the Guide.

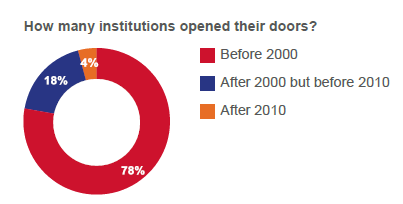

The overall conclusion is that the rise of arbitral institutions in Latin America has continued and has now spread to the Caribbean. Almost eighty percent of the institutions surveyed in the Guide were established before 2000; while eighteen percent were established after 2000 but before 2010; and five institutions in the Caribbean were established since 2010. The latest institutions to open their doors after 2010 include the Cayman International Mediation and Arbitration Centre, the BVI International Arbitration Centre, and Barbados’ Arbitration and Mediation Court of the Caribbean

The overall conclusion is that the rise of arbitral institutions in Latin America has continued and has now spread to the Caribbean. Almost eighty percent of the institutions surveyed in the Guide were established before 2000; while eighteen percent were established after 2000 but before 2010; and five institutions in the Caribbean were established since 2010. The latest institutions to open their doors after 2010 include the Cayman International Mediation and Arbitration Centre, the BVI International Arbitration Centre, and Barbados’ Arbitration and Mediation Court of the Caribbean

This is consistent with the arbitral communities’ focus on promoting arbitration in the Caribbean, including the ITA’s own Caribbean Task Force as part of the Americas Initiative launched in 2021. This data shows that institutional arbitration in Latin America has history that extends over a quarter of a century. While this may not compare to global arbitral institutions such as the PCA, ICC, LCIA, or SCC that may date back to the 1800s or early 1900s, it still shows sufficient experience and stability, which has been maintained since the 2011 Inaugural Guide. We discuss other key takeaways from the Guide below.

International Arbitrations Administered in Latin America

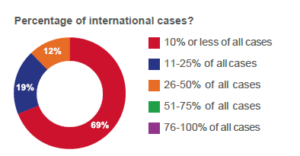

Although many Latin American countries aspired attracting international arbitrations from abroad in adopting model UNCITRAL or general international arbitral laws, this trend is still relatively low compared to the abundance of domestic disputes. A large majority of the institutions report having had ten percent or less of international cases. This is a slight decrease from the 2011 Guide reporting approximately twelve percent of disputes with foreign parties.

Some institutions, however, are situated high above the average and almost half their cases involve foreign entities. For example, the Centro Empresarial de Conciliación y Arbitraje in Venezuela and Centro de Arbitraje de la Cámara de Caracas, Venezuela both recorded between twenty-six and fifty percent of cases as international cases.

All of the institutions reported that – in only ten percent or less of the cases – the seat and the venue of arbitration was located outside of the institution’s country. This shows that the parties’ selection of a certain Latin American institution is usually tied to the selection of that same venue and the venue’s arbitral regime. Typically, in high-scale projects, foreign investors are required to create local special purpose vehicles (SPVs), which in turn, may skew the numbers as these disputes might be deemed domestic. Local legal representatives and transactional lawyers may tend to include arbitration provisions under regional arbitral institutions, unless the clause receives pushback from foreign owners or investors in the SPVs.

Arbitrating Against Public Entities

The Guide seems to suggest a slight decrease in cases involving a public entity as a party. In a grand majority of the cases, there were ten percent or less cases where a party is a state-owned entity or the State. At the same time, in fourteen percent of the cases, this participation fluctuated between twenty-six and fifty percent. Some of this fluctuation may be a result of mandatory arbitration clauses in public contracts such as in countries like Peru. Indeed, El Centro Nacional e Internacional de Arbitraje de la Cámara de Comercio de Lima, Peru, recorded between fifty-one percent and seventy-five percent of all cases in 2021 as cases with public entities. The mandatory involvement of the State in arbitration has created an enormous volume of arbitration cases, which in turn has contributed to the growth and the maturity of the local arbitral community.

Selection of Arbitrators

Party autonomy is key in choosing an arbitral institution. The Guide shows that in ninety percent of the institutions, it is not necessary for the arbitrator to be a national of the State where the institution is located. Twenty-nine percent of the institutions answered “yes” to needing to be licensed in the jurisdiction for domestic cases but only ten percent answered “yes” for international cases, showing a very welcoming atmosphere for international disputes. The nationality of the arbitrators has been a long-standing issue in many Latin American jurisdictions, where a proposed arbitrator needed to be a qualified lawyer in that jurisdiction and, in some cases, to be a lawyer, the person had to be the national of that State. The relevant message for the foreign parties is that this requirement is almost extinct.

In fifty-three percent of the institutions surveyed, the parties are required to choose arbitrators from the institution’s roster of arbitrators, while in forty-seven percent of the institutions surveyed parties are free to appoint arbitrators. Originally, Latin American institutions opted for rosters to provide some sort of prescreening process of all arbitrators to give the community additional quality assurance of the arbitration services. However, in response to the demand for an increase in autonomy in disputes, institutions have allowed more appointments outside of the rosters.

Interim Measures and Emergency Arbitrator Proceedings

Another hot topic covered in the Guide are interim measures and the ability to appoint an emergency arbitrator. Sixty-seven percent of the institutions reported having emergency arbitration procedures in their rules, and all institutions reported the ability to issue interim measures. Most Latin American legislations have traditionally considered arbitrators as acting in a private capacity under a mandate received from the parties. Consequently, whether an arbitrator can direct interim measures toward third parties continues to be applied inconsistently in each jurisdiction. Notably, in Chile, as an illustration, national arbitrators are known to possess quasi-judicial features comparable to local judges and are authorized to issue interim measures towards third parties such as banks and public registers.

Dispositive Motions

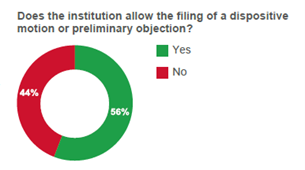

As the need for more efficiency and reduced costs in arbitration continues to be demanded by the international arbitration community, procedural tools such as dispositive motions have continued to become more common in jurisdictions throughout the world and now within the Latin American region.

The majority of the institutions surveyed responded that dispositive motions or preliminary objections are available under their institutional rules.

The majority of the institutions surveyed responded that dispositive motions or preliminary objections are available under their institutional rules.

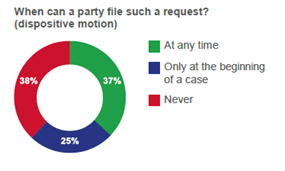

Interestingly, a quarter of the institutions surveyed only allowed dipositive motions at the beginning of the case, while thirty-seven percent allowed them at any point. We hope to see how these types of motions continue to be viewed by the region, particularly in the enforcement stage of an award which disposed of a case via a summary proceeding.

Interestingly, a quarter of the institutions surveyed only allowed dipositive motions at the beginning of the case, while thirty-seven percent allowed them at any point. We hope to see how these types of motions continue to be viewed by the region, particularly in the enforcement stage of an award which disposed of a case via a summary proceeding.

Diversity and Appointment of Female Arbitrators

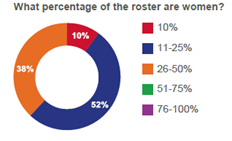

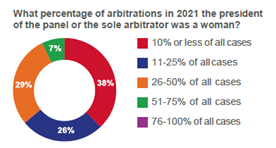

Diversity in the appointment of women arbitrators continues to be a pressing issue in international arbitration. In ten percent of the institutions, female arbitrators account for only ten percent of the arbitrators on the lists. In the majority of the institutions surveyed (fifty-two percent), the numbers varied slightly higher; between eleven and twenty-five percent of the lists comprised of woman arbitrators. However, this number significantly increased in the context of a woman as the sole arbitrator or president of the tribunal. That same year, thirty-six percent of institutions reported twenty-six to seventy-five percent of the cases included a woman as the sole arbitrator or presiding arbitrator.

Considering that the sole arbitrator or presiding arbitrator is appointed by the institutions more frequently than the co-arbitrators, it might show the institutional effort to increase the appointments of women. While the numbers continue to be low, the overall appointment of women is much higher compared to earlier decades.

Conclusion

Undoubtedly, the ITA Guide to Arbitral Institutions in Latin America shows an interesting picture consistent with a considerable development of arbitration in the region, but also is indicative of the needs that may be addressed in the future. In our opinion, the institutions would benefit if they are able to attract more international cases, as it would increase participation of foreign arbitrators and legal representatives, nurturing local arbitration practices and communities. In sum, the Guide provides a concise and consolidated review of the relevant arbitral institutions in the Latin America region, which we hope will lead to the best practices and increase to their utilization for cross-border disputes.

We would like to thank all the institutions that participated in this Guide. Their willingness to share information is extremely valuable for the arbitration community.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.