When the USMCA entered into force on 1 July 2020, the general view was that the agreement would limit the ability of investors to file investment arbitration claims because the new rules offered limited access to the ISDS mechanism compared with NAFTA. Furthermore, investors from Canada and the U.S. face an additional restriction as ISDS rules expired between the two countries after a three-year transition period that expired on 30 June 2023. As of that date, U.S. investors cannot file an ISDS claim against Canada, and Canadian investors cannot file an investment claim against the U.S. Regarding Mexico and Canada, the situation is similar with one distinction. Since Mexico and Canada are Contracting Parties to the CPTPP, investors from those countries still have access to ISDS.

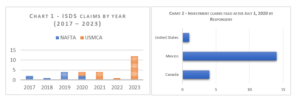

Due to all the new features in the ISDS rules, there was also an expectation that investors of the three countries would use the transition period to file ISDS cases under the NAFTA rules to the extent possible instead of using the new ISDS rules under the USMCA during the first three years of its existence. As this post shows, the expectation proved to be correct because the number of cases registered during the first three years of the USMCA was higher in comparison to the last three years of the NAFTA.

In light of the recent conclusion of the transition period, this post examines some of the new features in the USMCA Investment Chapter, reviews the cases registered during the first three years of the agreement, and identifies some areas of potential interpretation of the new provisions that will likely start emerging in 2024.

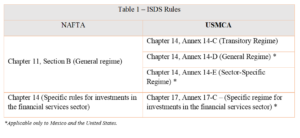

ISDS Rules at a Glance

As plenty of experts have written about the USMCA Investment Chapter, this post will provide an overview of some of the new features of the ISDS rules instead of discussing the chapter itself.

Unlike NAFTA Chapter 11 (Investment), the ISDS rules were segregated into annexes designed to address different procedural requirements and claims (see Table 1 below). Under Annex 14-C, investors of the three Parties could submit a Chapter 11 claim within three years of USMCA’s entry into force, subject to certain conditions. For instance, the access to that annex, known as the Legacy Investment Clause, was limited to investments of an investor of a Party in the territory of another Party established or acquired between 1 January 1994, and the termination of the NAFTA and in existence on the date of entry into force of the USMCA (i.e., 1 July 2020). However, as of 1 July 2023, Annex 14-C is no longer available for submission of claims to arbitration.

Annex 14-D contains the main body of ISDS rules available to U.S. and Mexican investors regardless of the economic sector in which they have invested, similar to NAFTA Chapter 11, Section B. However, two significant differences between the two agreements arise regarding claims that an investor can submit to arbitration. First, under the USMCA Annex 14-D, only breaches of the following USMCA obligations can be arbitrated: (i) National Treatment, (ii) Most-Favored-Nation Treatment, and (iii) direct expropriation.

Second, the application of an exhaustion of local remedies clause. Investors (when filing a claim on its own behalf) and the investor and the enterprise owned or controlled by the investor (when filing a claim on behalf of the enterprise) must: (i) have first initiated a proceeding before a tribunal or court of the respondent party, and (ii) obtained a final decision from a court of last resort or 30 months have elapsed from the date the proceeding was initiated. The requirement is not applicable if recourse to domestic remedies is “obviously futile.”

USMCA Annex 14-E takes the opposite approach with respect to the two limitations mentioned above. First, the investor may submit a claim to arbitration for any standard of protection outlined in Chapter 14. Second, the limitations on the exhaustion of local remedies in Annex 14-D are not applicable. However, Annex 14-E is only available to investors (and, in some cases, an enterprise of the host country owned or controlled by the investors) that are a party to a contract with the government of the host country in five sectors: oil & gas, power generation, telecommunication services, transportation services, and infrastructure projects (i.e., roads, railways, bridges, or canals).

Finally, the USMCA maintains specific ISDS rules in the Financial Services Chapter (see post).

USMCA Caseload

In the first three years of USMCA, 19 cases were registered (see Chart 2) compared to nine cases during the last three years of NAFTA (see Chart 1 below). Remarkably, Mexico is the respondent party in 14 of the 19 claims filed under the USMCA, representing 73.6% of the total cases. However, it should be mentioned that one case was discontinued in 2022 (L1bre v. Mexico), and another one stayed in 2023 (Sepadeve v. Mexico). Canada and the U.S. are respondents in four and one cases, respectively (see Chart 2 below).

Interestingly, in the case of Mexico, 10 of 14 arbitration cases under the USMCA were registered in 2023, mainly filed by U.S. investors. That figure represents 71% of USMCA cases against Mexico in the first three years. Overall, it is yet to be seen if more claims will be registered in the last part of 2023. Still, this year can be considered atypical due to the vast number of claims filed, but the expiration of the Legacy Investment Clause at the end of June 2023 could explain the increment in claims. Thus, a significant decrease in claims filed during the rest of 2023 should be expected.

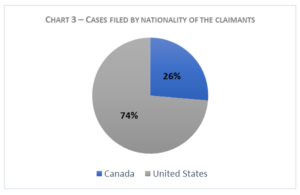

Like NAFTA, U.S. investors continue to be the primary users of ISDS in the USMCA era, followed by Canadian investors with 26% of claims (see Chart 3 below). Mexican investors still have not filed an ISDS case under the USMCA.

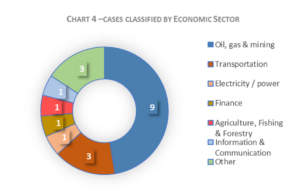

A review of the economic sectors involved in cases filed under the USMCA, as per the classification used by the ICSID, reveals that 48% of the cases related to the oil, gas, and mining industries. Additionally, 16% relate to transportation. Other sectors report one case as shown in Chart 4, and three cases are classified as “other industry”.

As discussed in this blog, there was speculation about potential ISDS cases against Mexico due to the reforms and policies that President Lopez-Obrador sought to adopt to roll back the 2013 constitutional reform that opened the energy sector to private investment. However, although the cases filed under the USCMA mostly pertain to the energy industry, none are related to President Lopez-Obrador’s reforms.

Development of USCMA Case Law

With the claims filed under the USMCA, we will witness the formation of case law on the new investment provisions.

In TC Energy v. U.S., the claimants filed a notice of arbitration under NAFTA using Annex 14-C, alleging that President Biden’s revocation of a permit to construct a pipeline on 20 January 2021, breached the NAFTA Investment Chapter. The U.S. challenged the tribunal’s jurisdiction to hear the claim, alleging that in Annex 14-C, Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. only extended their consent to arbitrate claims that arose before NAFTA’s termination (i.e., 1 July 2020). At the core of the dispute is Annex 14-C(1), which provides that:

As discussed in this post, Annex 14-C does not explicitly address the question at issue as it does, for instance, regarding the duration of the USMCA Parties’ consent to arbitrate disputes under NAFTA upon termination. Thus, the disputing parties have been arguing different interpretations, and recently, Mexico filed a non-disputing Party submission under NAFTA Article 1128, siding with the U.S. At the moment, the position of Canada on this matter remains unknown. The tribunal will interpret Annex 14-C to decide whether the USMCA Parties consented to arbitrate claims under NAFTA only with respect to alleged breaches of the agreement that occurred while it was in force or, as TC Energy claims, also during the first three years of the USMCA.

The tribunal’s decision (or award) on this matter will set an important precedent for cases filed more recently under USMCA Annex 14-C against Mexico and Canada. One of the cases that would probably benefit from the precedent is Access v. Mexico, where the claimant alleges that its investment was expropriated by SEDATU (a federal agency) after 1 July 2020.

Another relevant case to follow is Finley v. Mexico, which is the first case with claims filed under Annex 14-E (i.e., ISDS related to covered government contracts). The claimants allege that Pemex Exploration and Production, a PEMEX subsidiary (Mexico’s oil and gas state-owned enterprise), repudiated three contracts the claimants entered into with the company for oilfield services. Some claims in this case were submitted under NAFTA (via Annex 14-C), while others were filed under Annex 14-E. Among other arguments, Mexico contends that the tribunal lacks jurisdiction to hear the claims because the USMCA Parties did not consent to submit claims before a single arbitral tribunal under different international investment treaties (i.e., NAFTA and USMCA). Mexico relies on Article 14.2(4) that provides that:

“For greater certainty, an investor may only submit a claim to arbitration under this Chapter as provided under Annex 14-C (Legacy Investment Claims and Pending Claims), Annex 14-D (Mexico-U.S. Investment Disputes), or Annex 14-E (Mexico-U.S. Investment Disputes Related to Covered Government Contracts).”

The Claimants seem to argue that they did not file all their claims under NAFTA because footnote 21 in Annex 14-C does not allow filing claims under that agreement when the investor of a Party is eligible to submit claims to arbitration under USMCA Annex 14-E. Footnote 21 states:

“Mexico and the U.S. do not consent . . . with respect to an investor of the other Party that is eligible to submit claims to arbitration under paragraph 2 of Annex 14-E.”

Thus, following the Claimants’ argument, the claims brought under Annex 14-E could have been originally filed under NAFTA Annex 14-C. Still, because of the limitation on consent in footnote 21, those claims had to be filed under Annex 14-E. This would explain why the Claimants filed some claims under the USMCA and others under the NAFTA, but the tribunal will have to decide whether the claimants’ interpretation was correct. On 31 August 2023, the U.S. filed a non-disputing party submission in this arbitration, but it was unavailable at the time of writing this blog.

Conclusions

As of 1 July 2023, only the investors from the U.S. and Mexico have access to the new ISDS rules. Accordingly, we should expect a significant decrease in the number of cases under the USMCA not only because Canada is no longer a Party to ISDS but because of the limitations in annexes 14-D and 14-E. Also, if new cases emerge, they will likely be filed by US investors against Mexico based on the trend shown by previous cases.

Finally, under the USMCA, Canada, Mexico and the U.S. will have an opportunity in 2026 to review the performance of the agreement, including the Investment Chapter. This opportunity could lead to Canada being a Party to the ISDS rules or improving such rules.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.