Evidence is the beating heart of almost every dispute, and there is no exception in international arbitration. Therefore, the ‘Evidence in International Arbitration Report’ (Report) recently released by the Australian Centre for International Commercial Arbitration (ACICA) and FTI Consulting on 6 September 2023 will be invaluable for arbitration users looking to test and improve their approach to evidence.

The Report is instructive in respect of both prevailing practice, and pathways forward for identified pain points for the treatment of evidence in international arbitration. This is achieved through the data and insights from 64 respondents who act as counsel, arbitrator and/or expert in arbitrations predominately in Australia and Asia, as well as through editorials from thought leaders. ACICA remarked in its introduction that it “did not want to focus only on how evidence is treated currently, but also how current practice could be improved.”

An emerging theme from the Report is the conflict between parties’ desire to not be ‘cut-off at the knees’ when presenting their case and their wish for a more time- and cost-efficient approach to the resolution of their dispute. With this conflict in mind, it may fall on the tribunal to ‘tame’ the evidence. It is notable that, over ten years ago, Dr Christopher Boog in ‘The Lazy Myth of the Arbitral Tribunal’s Duty to Render an Enforceable Award’ opposed “an almost debilitating prudence” in the conduct of arbitrations due to tribunals’ concerns regarding the enforceability of their awards and encouraged arbitrators “to seize the reins of the proceedings.” However, further encouragement is clearly needed. As Toby Landau KC observed in his concluding remarks of the Report, the results of the Report:

“tread directly on what is perhaps the single most important tension that now lies at the heart of international arbitration practice: the tension between the widespread agreement that arbitral tribunals need to take proactive steps in managing and intervening in arbitral proceedings, and the widespread reluctance on the part of international tribunals to do so.”

Status Quo: Taming Needed

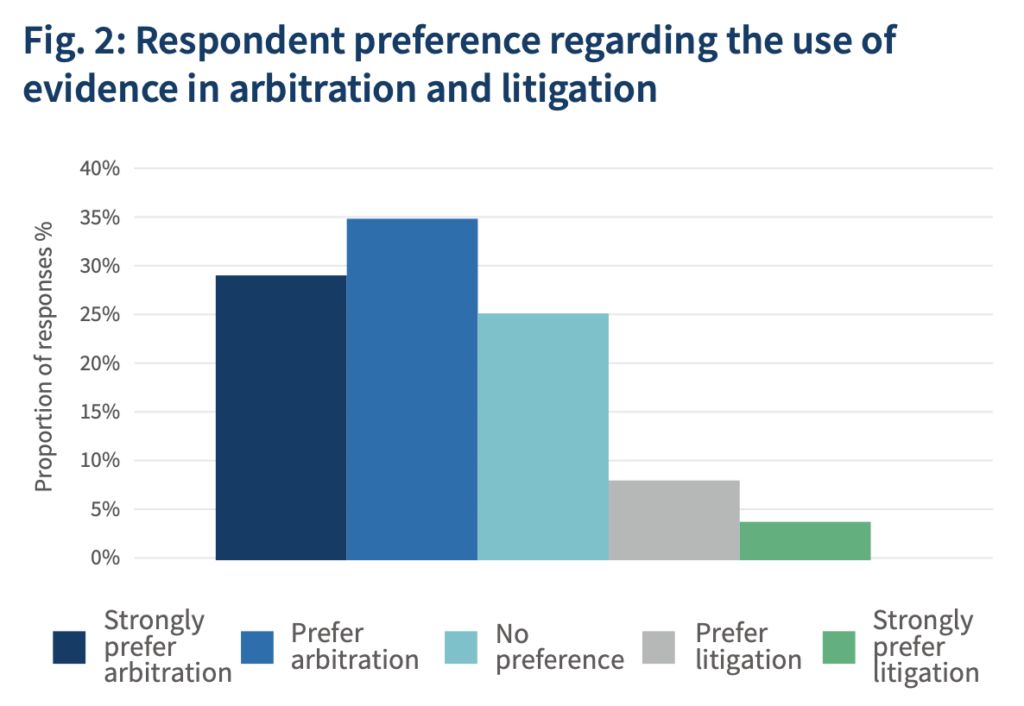

By way of scene setting, the prevailing majority of respondents (64%) preferred the treatment of evidence in international arbitration to litigation (Fig. 2).

Factors in favour of arbitration included the reduced scope of document production, the streamlined approach to cross-examination, and a more logical approach to the admissibility and relevance of evidence. It may be for these (and no doubt other) reasons that respondents overwhelmingly (85%) indicated satisfaction with their experience in using and/or giving evidence in arbitration.

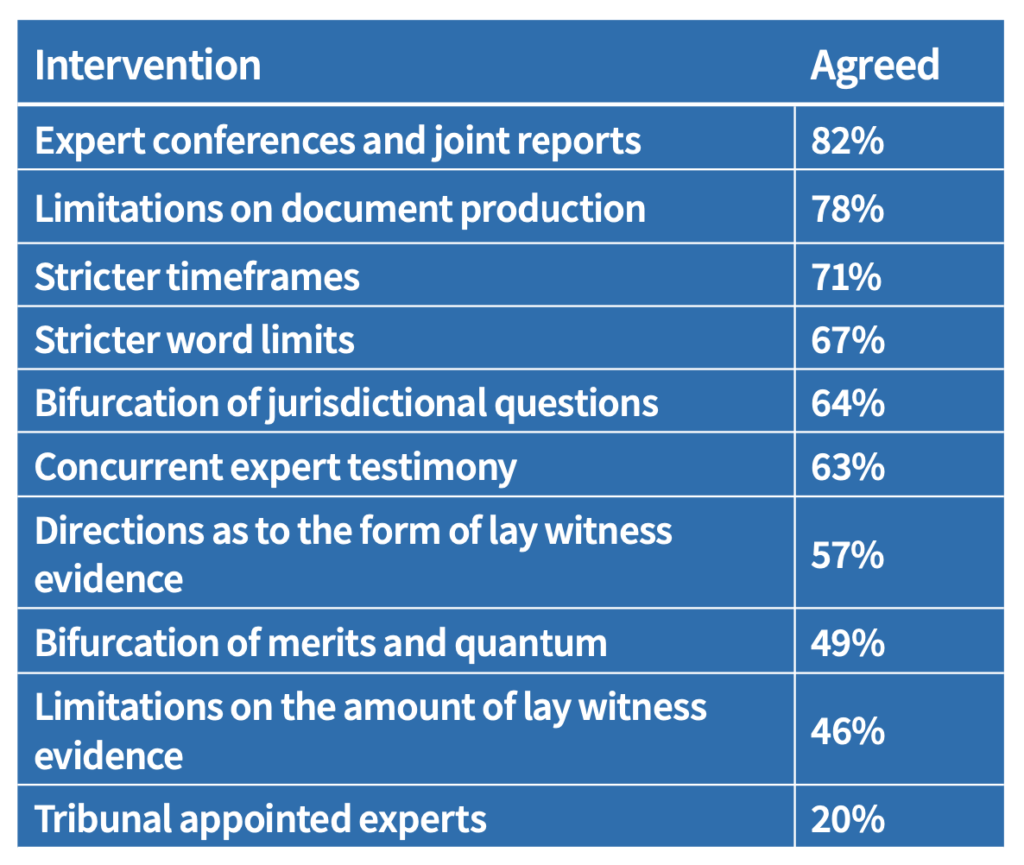

However, almost all respondents (96%) considered that the use of evidence in international arbitration would be improved by greater tribunal intervention, indicating an appetite for arbitration to better realise its intended efficiency. In particular, respondents indicated a desire for greater tribunal intervention in respect of the following interventions:

It might be argued that enacting these measures may curtail a party’s right to present its case. Whether limiting discovery means that a party has lost its right to present its case fulsomely remains an open question, particularly where a party is from a common law jurisdiction and is accustomed to discovery.

For tribunals to take this desired intervention, Toby Landau KC considered that: counsel must not stoke the ‘due process paranoia’ of tribunals by levelling dubious submissions concerning a lack of due process; more information is needed regarding the prospects of due process challenges; and more “spine” is needed from tribunals. Ultimately, it is about finding a balance between giving parties a reasonable (but not exhaustive) opportunity to present their case (and evidence) and resolving the dispute in a time- and cost-efficient way. Finding this balance is far simpler in theory than in practice, as an examination of the different types of evidence reveals.

Documentary Evidence: Thinning the Herd

Unsurprisingly, it was reported that “[a]cross the board respondents considered documentary evidence to have a significant impact on case outcomes.” This aligns with the sentiment that ‘documents don’t lie’, as noted by Dr. iur. Clarisse von Wunschheim, perhaps except in a case of documentary fraud or forgery.

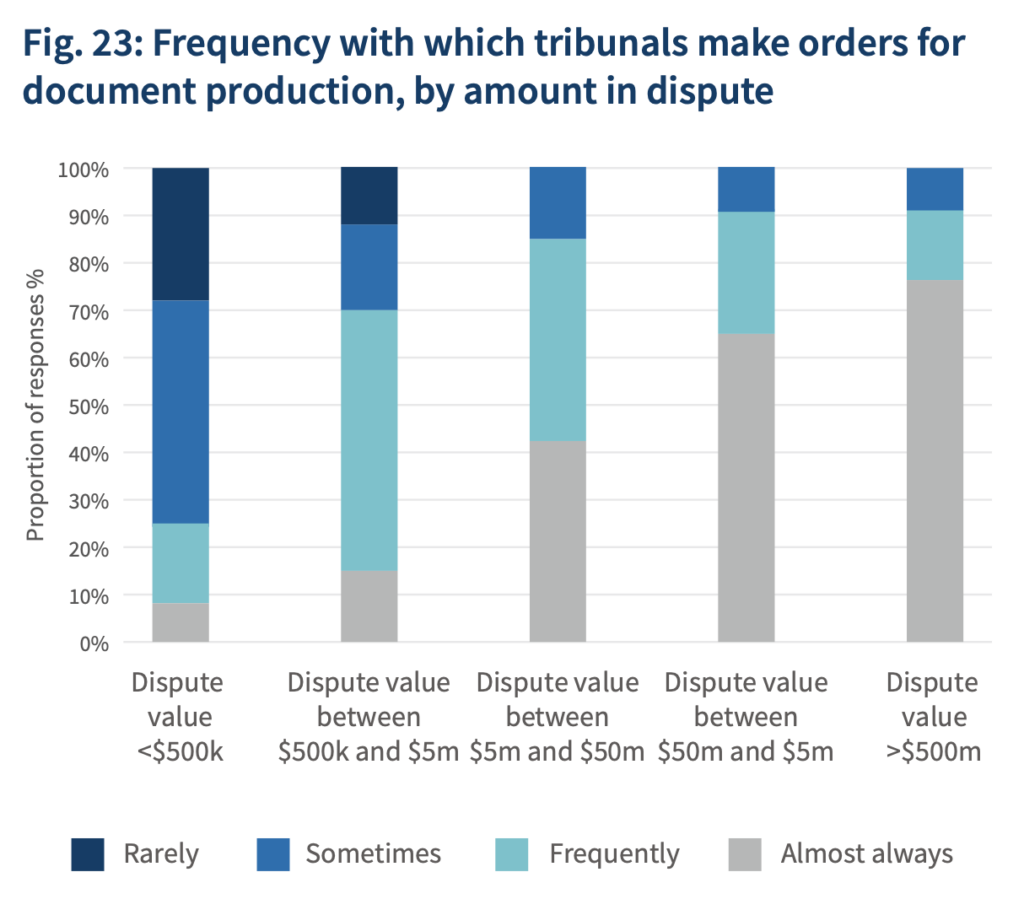

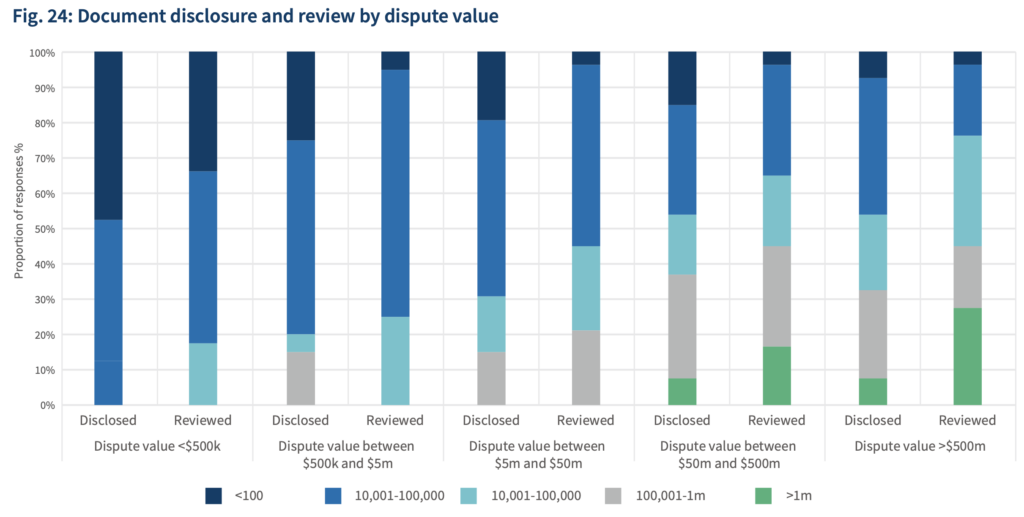

The Report confirmed that the likelihood of document production, together with the volume of documents reviewed and disclosed (and, therefore, the associated time and cost spent) correlated with the amount in dispute (Figs. 23 and 24).

This trend is not unexpected, as one would expect parties with more ‘skin in the game’ to seek a fuller ventilation of the universe of documents relevant to the issues in dispute. However, it demonstrates a ripe opportunity for greater tribunal intervention in respect of document production in circumstances where great time and cost is at stake. Notwithstanding this, Benjamin Hughes observed that “[t]ribunals are sometimes reluctant to deny or limit requests for documents which may later turn out to be relevant and material to the outcome of the case” as they may find it “more expedient (and safer) to simply grant dubious requests.”

Tribunals’ appetites for thinning the herd of documents should be fortified. Respondents indicated that the critical documents were often those already in the possession of the relevant party, and that documents produced via production were usually less relevant. This must be caveated in the case of information asymmetry. For example, in a post-closing M&A dispute where the buyer (now in possession of the target company) alleges breach of warranty on the part of the seller, there is an obvious inequality of arms that would likely necessitate document production to enable the seller to mount a defence and prevent the buyer from being able to cherry-pick documents in a misleading way. However, even in this circumstance, targeted document requests around those supporting documents could mitigate the issue.

The editorialists offered solutions to minimise cost blow-outs for discovery. The way forward proposed by The Hon. Wayne Martin AC KC was “conferral between sensible practitioners.” In his view, counsel should think hard about the scope of document requests being sought, considering that a ‘smoking gun’ or ‘Holy Grail’ document is almost never obtained. Benjamin Hughes instead proposed two procedural interventions for delimiting document production: (a) production of a list of issues after the first round of submissions to guide document production; and (b) a simpler document request schedule identifying the relevance of documents to those issues. Another way forward is to adopt the civil law approach outlined by Dr. iur. Clarisse von Wunschheim namely to restrict document production to those documents necessary to prove a party’s case. Although, from a common law perspective, this may inhibit the discovery of truth, if that is the aim of a decision-maker.

Lay Evidence: It’s All in the Preparation

Whilst respondents “considered lay witness evidence to have a significant impact on case outcomes,” they took the view that it had “the least impact compared with expert evidence and documentary evidence.” This view seems to support the primacy of documentary evidence, particularly in the electronic era, where documents provide an almost complete record of the events that transpired. Lay evidence is seen to have taken a back seat, limited to adding context and narrative to the documentary record. However, it is also important to keep in mind, as Dr. iur. Clarisse von Wunschheim points out, that lay and documentary evidence “go hand in hand” and lay evidence can fill in gaps in the record, as well as bring life and colour to the documents.

As a useful practical point, the consensus view of 78% of respondents was that lay evidence is most compelling where it addresses both contemporaneous documents and witness experiences together. This contrasts with a witness statement operating merely as a vessel to produce documents or dealing only with witness experiences. However, The Hon. Wayne Martin AC KC cautioned practitioners that lay evidence ought not be “argumentative or tendentious.”

Building on these words of caution, and in furtherance of the ICC Report on Witness Memory, Professor Kimberley Wade outlined the risks associated with the preparation of evidence and its influence on a witness’s memory and, therefore, the reliability of their testimony. Arbitration practitioners were advised to “use neutral, open-ended questions and avoid giving witnesses feedback or steering them towards a particular version of the facts.”

Expert Evidence: A Firm Hand on the Reins

Respondents overwhelmingly (82%) considered “the involvement of experts to have a significant impact on case outcomes.” However, respondents indicated a concern that expert evidence was unhelpful particularly where the reports were ‘ships passing in the night’ with diverging instructions. With this in mind, respondents indicated a desire for tribunals to assist in narrowing or settling the questions for the experts. As noted above, another way of addressing this issue, favoured by 82% of respondents, was for tribunals to intervene in respect of expert conferences and the preparation of joint reports.

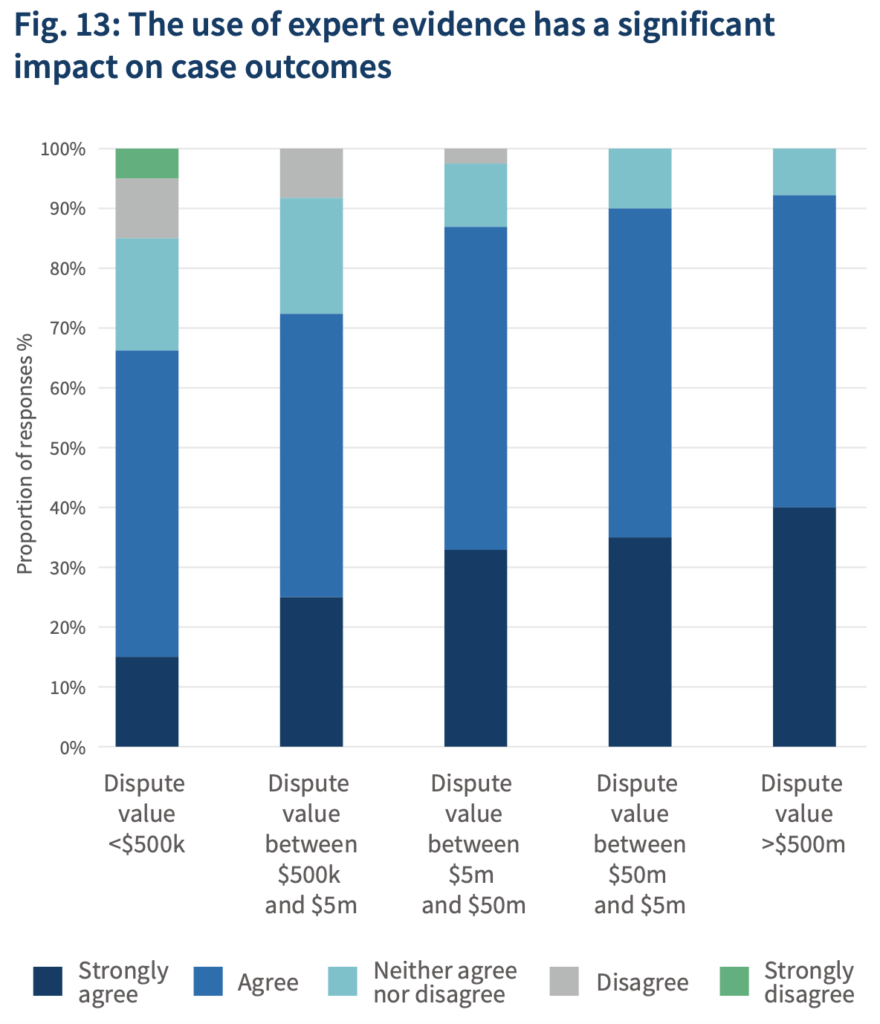

The Report confirmed that the likelihood of using expert evidence is correlated with the quantum in dispute. Interestingly, the Report also identified a correlation between the amount in dispute and the impact of expert evidence (Fig. 13). Whilst this might be chalked up to a starting presumption that high quantum disputes are always highly complex, this is by no means true in all cases. The reasons behind the respondents’ responses are therefore unclear.

A pain point for expert evidence in arbitration was identified as being “the lack of emphasis on the duty of the expert to the tribunal.” For experts new to the field of arbitration, John Temple-Cole and Martin Cairns emphasised the need to appraise them of their duties. For Dawna Wright, keeping this duty in mind was the secret to producing an effective joint expert report that narrows the issues.

Conclusion

Overall, the Report demonstrates that the treatment of evidence in international arbitration is an advantage over litigation and a key opportunity for arbitration to be more efficient. While many arbitration users are keen for the tribunal to ‘take the reins,’ it is also up to parties to put on their case effectively. This comes down to who the parties appoint as their tribunal, whether the parties have the confidence to put on their best case rather than their most comprehensive one, and whether they best use the tools available to them (including, and especially, their evidence). Discipline from tribunals and parties alike may be required to prevent the ‘horse’ from ‘bolting.’

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.