Introduction

Procedural fairness is a fundamental principle in international commercial arbitration, which ensures that parties have a fair opportunity to present their case. The 1958 New York Convention (hereinafter “NY Convention”)—particularly Article V.1.(b)—plays a crucial role in upholding this principle. This provision provides that the court of a contracting State may refuse to recognize and enforce an arbitral award if the party against whom it is invoked furnishes proof that it “was not given proper notice of the appointment of the arbitrator or of the arbitration proceedings or was otherwise unable to present his case.”

What exactly does this provision mean? Its meaning has been the subject of extensive scholarly debate. Does this provision entail a uniform substantive rule that enshrines international arbitration standards, a uniform conflicts rule that implicitly points to national law, or something else entirely? An empirical analysis of this issue could move the discussion beyond fixed theoretical positions and towards a more concrete and practical understanding of the NY Convention.

A recent empirical study conducted by the author provides valuable insights into how courts apply these procedural fairness standards. The study examined over 200 judicial decisions related to the NY Convention across six jurisdictions up to 2023: England and Wales (15), Singapore (8), Hong Kong (22), Switzerland (22), the United States (129), and Portugal (6). This selection of jurisdictions represents a diverse sample, which includes both civil law and common law systems, as well as jurisdictions that have adopted the UNCITRAL Model Law and those that have not. The former group has recently been recognized as among the most popular seats of arbitration (see here). In the absence of comparable studies on enforcement practices, it is reasonable to infer that courts in these jurisdictions are more experienced in handling arbitration-related matters, even if their role is primarily limited to facilitating arbitral proceedings or exercising judicial oversight.

This blog post highlights three key findings from the study discussed above.

Key Findings on Procedural Fairness Standards

The primary focus of the study was on the different procedural fairness standards applied by courts under Article V.1.(b) of the NY Convention: international arbitration standards under a substantive rule, domestic national standards under an implied conflicts rule, or otherwise.

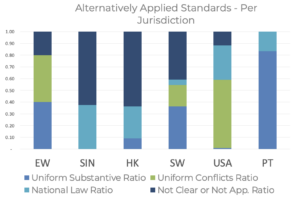

Diverse Interpretive Approaches: Table 1 shows that courts in the selected jurisdictions adopt different approaches to interpreting Article V.1.(b).

Specifically, English courts yield mixed results, equally split between solutions favouring a uniform substantive rule and a uniform conflicts rule. Hong Kong courts predominantly adopt a national law reference position, with a few cases endorsing the uniform substantive rule. This “national law reference” includes instances where courts applied national law standards without explanation or private international law analysis. Swiss courts also alternate between the preferred uniform substantive rule, conflicts rule, and national law reference. In contrast, Singapore courts demonstrate a clear preference for national law standards. U.S. courts strongly favour the uniform conflicts rule, closely followed by general reference to national law. Portugal stands at the opposite end of the spectrum and opts for the uniform substantive rule.

The majority of the decisions—without weighting jurisdictional averages—interpret Article V.1.(b) as a uniform conflicts rule, a position reflected in U.S. jurisprudence. However, a comparison of the averages across jurisdictions reveals a more nuanced picture: on average, 28% of the decisions apply the uniform substantive rule (favoured in Switzerland and Portugal), followed by both national law reference approach (19%) and uniform conflicts rule alternative (19%), as seen in Singapore, Hong Kong, and the U.S. England and Wales appear divided across these positions.

Notably, 23% of all analysed decisions are unclear as to which procedural fairness standards they employ. These decisions often focus on the factual circumstances of the case and the parties’ expectations and intentions.

Consensus on (Some) International Arbitration Standards: Courts do not shy away from outlining the exact content of international arbitration standards relevant under Article V.1.(b) when applying this provision.

The analysis of 22 relevant decisions reveals a consensus: Article V.1.(b) is understood to safeguard the principle of audi alteram partem, broadly interpreted as the right to be heard, the right to a fair hearing, or the principle of natural justice, depending on the legal system in question. This protection is manifested in principles of adversarial procedure and procedural equality, including the requirement that parties are given adequate notice of proceedings (see here, here, and here). Courts also emphasize parties’ ability to present arguments and evidence (see here and here), challenge the opposing side’s submissions (see here and here), and respond to the tribunal’s factual findings (see here). Notably, courts consistently reject national judicial rules and practices when interpreting these principles (see here).

However, different approaches regarding iura novit curia are found in Switzerland and England. Swiss courts interpret it as part of the generally accepted right to be heard (see here), whereas England courts remain sceptical of its status as an established international arbitration standard (see here). Likewise, England courts impose a duty to provide reasons in arbitral awards (see here), while Switzerland courts impose no such obligation (see here). Nevertheless, both jurisdictions address the issues of arbitrator bias, independence, and impartiality (see here and here).

There is equally convergence in the sources cited, with general principles and NY Convention standards most frequently cited while national law sources are considered only incidentally.

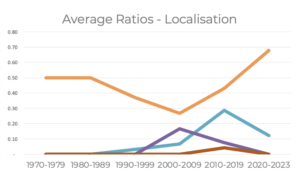

Prevalence of the Law of the Place of Enforcement: Table 2 confirms the dominant role of the law of the place of enforcement (cited in 134 decisions, and 97% of the decisions took a clear position on this issue) when Article V.1.(b) is interpreted as referring to national standards, both as a conflicts rule or as a general national law reference. The law of the arbitral seat is rarely applied, although it carries relatively greater weight in Swiss case law.

This emphasis on enforcement localisation traces its origins to the U.S. court’s 1974 decision in Parsons & Whittemore (see here), which was later cited by the English court adopting a conflicts rule to apply its own law (see here). Similarly, the first Singaporean decision to take this same position (see here) relied on the 1993 Hong Kong Paklito decision (see here), the earliest judgment in that jurisdiction to adopt an enforcement-centric approach.

The nuance introduced with the lenient enforcement highlights a more circumscribed application of the standards of the place of enforcement. This manifests either in restricting its scope compared with domestic constitutional standards—such as in the U.S. (see here)—or in a more open attitude towards the internationalization of domestic standards, as seen in Hong Kong (see here), Switzerland (see here and here), and Portugal (see here).

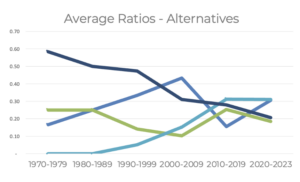

Unfinished Evolution: As shown in tables 3 and 4, although national law standards remain predominant globally, there is a growing shift towards applying international arbitration standards over time. This trend is particularly evident in Switzerland and Portugal, and is gaining ground in England. Concurrently, the number of decisions that fail to clearly identify the applicable standards has decreased over time.

Conclusion

The study of the selected jurisdictions reveals two competing trends in the application of Article V.1.(b): while national law standards continue to predominate, there is a gradual and promising shift towards recognition of international standards. This development—along with the marginal presence of alternative approaches and the greater judicial willingness to articulate and justify their chosen interpretive approaches—provides greater legal certainty in the field.

But does it even matter which standards courts apply under Article V.1.(b)? It indeed does—case law indicates that the choice between international arbitration standards and the standards of the place of enforcement can lead to different outcomes. This is illustrated by the Gol Linhas case (see here). In that case (see here and here), the defendant argued, inter alia, that the arbitral tribunal had adopted unexpected legal reasoning not advanced by the parties and without offering them an opportunity to respond. The U.K. Privy Council rejected this argument, noting that the award had survived scrutiny in annulment proceedings in Brazil. It therefore enforced the award under international arbitration standards, affirming that Article V.1.(b) imposed “a standard of due process capable of application to any international arbitration whatever the procedural law applicable and the nationality of the participants.” Notably, the Privy Council acknowledged that a different result might have followed under English domestic standards.

This empirical study thus provides valuable insights into the evolving landscape of procedural fairness standards in international arbitration. For practitioners and stakeholders, understanding these trends is crucial for navigating the complexities of enforcing arbitral awards under the NY Convention.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.