The first blog in this two-part series, published last year, discussed the growing concern of arbitration users over “due process paranoia”. In that first blog, due process paranoia was defined as the perceived reluctance by arbitral tribunals to act decisively (for example by rejecting applications for extensions of time, refusing amendments to submissions, rejecting new evidence or declining to reschedule a hearing) for fear of the award being challenged on the basis of a party not having had the chance to present its case fully. The issue of due process paranoia continues to take prominence within the international arbitration community. It was the topic of the 31st Freshfields Arbitration Lecture delivered by Professor Lucy Reed in October last year.

In our first blog, we argued that the concern with due process paranoia was that, when a tribunal opts for caution instead of procedural economy in circumstances where the tribunal could, in actual fact, afford to be robust (because the enforcement risk is lower than is believed to be by the arbitrators), the tribunal makes a ‘wasteful’, ‘sub-optimal’, decision. These wasteful, sub-optimal, decisions are particularly frustrating to parties when they are taken in response to what appears to be dilatory tactics employed by the other side. We argued that the solution to due process paranoia may therefore be found in a more precise assessment of the enforcement risk by arbitrators. This, in turn, is dependant on reliable data.

In that context, for our first blog, we conducted a systematic review of cases in our jurisdiction (England) reported since the enactment of the English arbitration Act (1996) in which an application had been made for setting aside an award. The purpose of this review was to assess whether, and if so in what circumstances, awards had been set aside in England because an arbitrator had taken an overly robust case management. This review showed that there was not a single judgment where an arbitration award had been set aside in England because the tribunal had taken an overly robust case management decision. Instead, most set aside decisions were due to arbitrators basing their award on arguments or evidence that had not been put forward to the parties during the proceedings.

Having focused on set aside proceedings in our previous blog, we now turn our attention to the other side of the equation, namely applications made to the English courts to resist enforcement of foreign awards. The relevant provision in this respect is s. 103 of the Act, which incorporates the grounds for the refusal of recognition or enforcement set out in Article V of the New York convention.

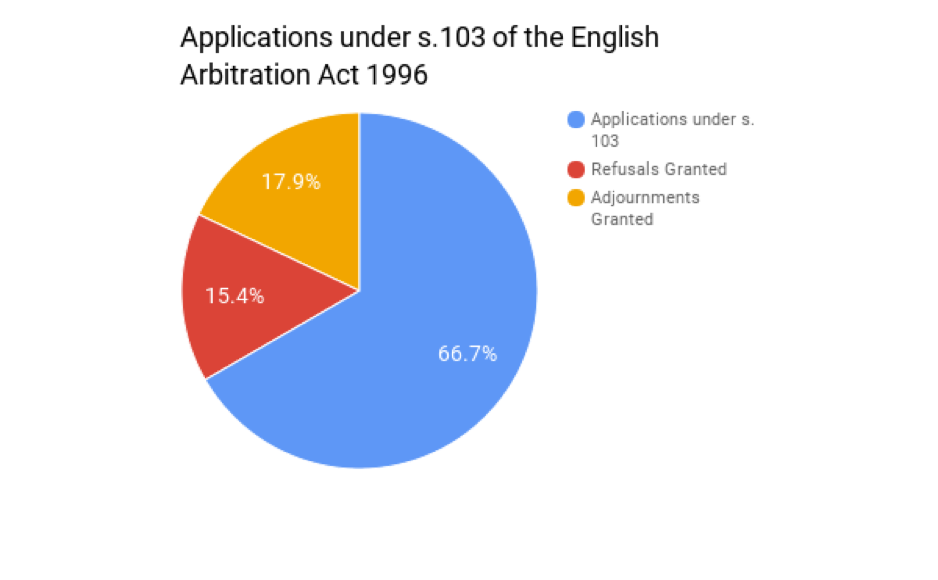

Adopting a similar approach to our previous blog, we systematically reviewed all English court judgments citing s.103 that have been reported since 1996. The search generated 57 judgments. If one excludes first instance judgments which were subsequently appealed, only 26 judgments actually dealt with s.103. The 31 other judgments included many instances in which either s.103 was simply cited in passing, or it was discussed as a related issue, not within the context of an application for refusing the enforcement of a New York Convention award.

Of the 26 English court judgments dealing with applications under s.103, the courts only refused to enforce a New York Convention award in 6 instances, and adjourned the enforcement of awards in 7 instances. This in itself shows that refusal to enforce New York arbitration awards is relatively uncommon in England, whatever the grounds.

More interestingly perhaps, our review of these judgments also showed that none of the instances in which an application under s.103 was granted arose out of a complaint that an arbitral tribunal had made an overly robust case management decision.

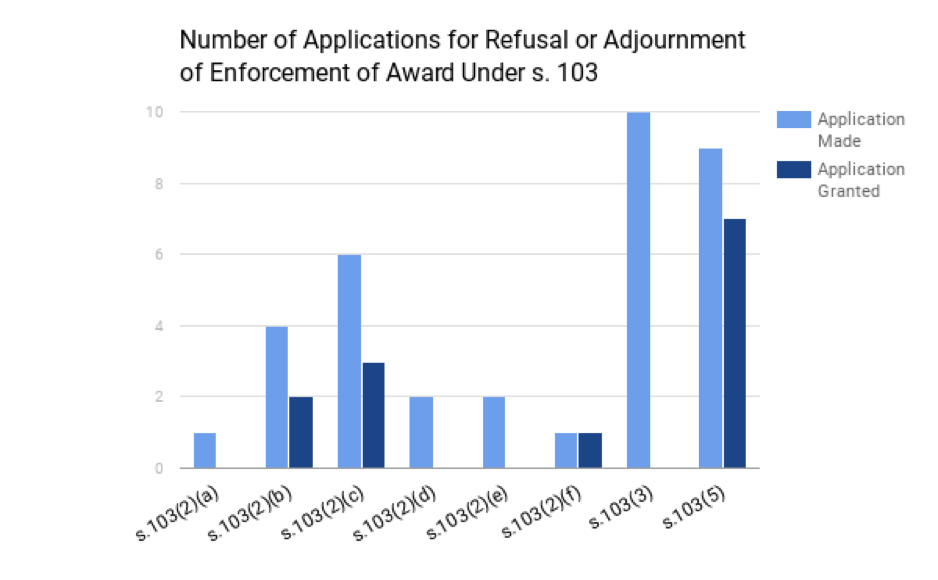

Under s.103 (as in under the New York Convention), a party can apply for the recognition or enforcement of an award to be refused on the following grounds:

- a party to the arbitration agreement was (under the law applicable to him) under some incapacity (s.103(2)(a));

- the arbitration agreement was not valid under the law to which the parties subjected it or, failing any indication thereon, under the law of the country where the award was made (s.103(2)(b));

- the applicant was not given proper notice of the appointment of the arbitrator or of the arbitration proceedings or was otherwise unable to present his case (s.103(2)(c));

- the award deals with a difference not contemplated by or not falling within the terms of the submission to arbitration or contains decisions on matters beyond the scope of the submission to arbitration (s.103(2)(d));

- the composition of the arbitral tribunal or the arbitral procedure was not in accordance with the agreement of the parties or, failing such agreement, with the law of the country in which the arbitration took place (s.103(2)(e));

- the award has not yet become binding on the parties, or has been set aside or suspended by a competent authority of the country in which, or under the law of which, it was made (s.103(2)(f); and

- the award is in respect of a matter which is not capable of settlement by arbitration, or if it would be contrary to public policy to recognise or enforce the award (s.103(3)).

Additionally, the court may also grant an adjournment on its decision on the enforcement of an arbitration award to pursuant to s. 103(5) of the Act, which is a temporary measure pending proceedings before the supervisory court to set aside the award.

Of the total cases, the ground most frequently relied upon for issuing refusal of enforcement applications related to breach of public policy (s.103(3)), which was raised in 10 instances.[1] Challenges under this subsection never succeeded.

The second ground most frequently relied upon was in relation to the parties complaint of their inability to present their case under s.103(2)(c). This ground is the one most closely associated with rules of natural justice. Therefore it is the one most likely to be used by parties seeking to challenge robust case management decisions.

Applications under s.103(2)(c) have succeeded in only three instances. Interestingly, of these three instances only one may arguably be said to relate (indirectly) to case management as discussed below.

All three decisions arose out of awards which relied upon information or arguments that had not been put to the parties:

- Malicorp Ltd v Egypt [2015] EWHC 361 (Comm): In this case the award had granted the claimant remedies on a basis which had not been pleaded nor argued.

- Irvani v Irvani [2000] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 412. In this highly unusual case, the arbitrator, who was the sister of the claimant and the respondent, had seemingly based her decision on information available to her, but not to the respondent.

- Kanoria & Ors V Guinness & Anor [2006] EWCA Civ 222. In this last case, a party to an arbitration was unable to present his case because he had never been informed of the case that he was required to meet.

This last case is perhaps the only one where case management comes into consideration, albeit indirectly. In that case, the party resisting enforcement of the award was suffering from a life threatening decease at the time of the arbitration, so that it was impossible for him to participate in the proceedings in a meaningful way. He had decided not to attend a hearing in a foreign jurisdiction. At that hearing, however, a case of fraud was made against him, of which he had not been made aware prior to the hearing. In the circumstances, the court found that, in breach of natural justice, he had not been informed of the case he was required to meet. While this could have been averted through proper case management (eg. by ensuring, at the very least, that the party who could not attend the hearing was made aware of the fraud claims made against him), the case does not concern an arbitrator taking overtly robust case management decisions to the detriment of a wasteful party trying the engage in dilatory tactics.

The fact that robust case management as such has not really prevented the enforcement of New York Convention Awards in England may be explained by the approach taken by the English courts in dealing with the operation of s. 103(2)(c). The approach is set out by Coleman J in In Minmetals Germany Gmbh v Ferco Steel Ltd [1999] 1 All ER (Comm) 315:

“In my judgment, the inability to present a case to arbitrators within section 103(2)(c) contemplates at least that the enforcee has been prevented from presenting his case by matters outside his control. This will normally cover the case where the procedure adopted has been operated in a manner contrary to the rules of natural justice. Where, however, the enforcee has, due to matters within his control, not provided himself with the means of taking advantage of an opportunity given to him to present his case, he does not in my judgment, bring himself within that exception to enforcement under the Convention.” (emphasis added)

Furthermore, Lord Philips CJ in his judgment in Kanoria & Ors V Guinness & Anor [2006] EWCA Civ 222 explained that s.103(2)(c) applies where a “a party to an arbitration is unable to present his case if he is never informed of the case that he is called upon to meet.” (paragraph 22 of the judgment). This was reaffirmed in Cukurova Holding AS v Sonera Holding BV [2014] UKPC 15. This approach suggest that arbitral tribunal must act in a wholly unreasonable manner in order to have an award refused under this ground, and it is unlikely to apply to instances where they have decided to act decisively by taking robust but fair case management decisions.

These findings, just like those of our first blog on the topic, re-affirm that arbitrators with a tendency for occasional due process paranoia should feel free to proceed robustly, at least whenever the likely place of enforcement is England and Wales.

[1] NB in HJ Heinz Co Ltd v EFL Inc [2010] EWHC 1203 (Comm), a summary application for a declaration that it would be contrary to public policy to recognise or enforce the award in England pursuant to the Arbitration Act 1996 s.103(3) was refused. Whilst the summary application was not successful, it cannot be immediately identified whether the s.103(3) argument succeeded in separate proceedings, and therefore this has not been included in the final count

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.