The ability of a party to obtain urgent interim relief is central to the efficacy of any method of dispute resolution. In case of disputes that are subject to an arbitration agreement, until recently parties had only two options: either approach national courts for interim relief in support of the arbitration, or wait for the formation of the arbitral tribunal and then make an application for interim relief. The former would essentially require parties to initiate local proceedings before national courts (the avoidance of which may in fact have been the principal reason for choosing arbitration in the first place). The latter would expose a party to the risk of dissipation of assets while the arbitral tribunal is being constituted.

Emergency arbitration is often cited as one of the solutions to the parties’ conundrum. But is emergency arbitration genuinely a substitute to urgent interim relief from courts? In this article, we compare the pros and cons of obtaining urgent interim relief from national courts and emergency arbitrator. In doing so, we focus on India’s experience and provide statistics from the practice of Indian courts.

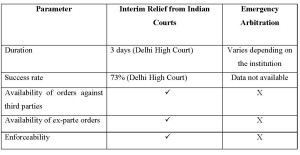

Relevant Parameters

By way of background, under Section 9 of India’s Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (the Act), Indian courts can grant interim relief in support of arbitration. Parties can approach courts for interim relief at any point before the constitution of the arbitral tribunal. However, after the tribunal has been constituted, parties are generally expected to seek interim relief from the tribunal directly. Further, interim relief from Indian courts is available even in cases where the seat of arbitration is outside India, unless the parties have agreed otherwise.

As for emergency arbitration, while the Act makes no reference to it, rules of Indian arbitration institutions – such as the Mumbai Center for International Arbitration and the Indian Council of Arbitration – allow parties to seek orders from emergency arbitrators. Moreover, Indian parties are often involved in emergency arbitration proceedings conducted by foreign institutions, particularly SIAC.

The table below contains a comparison of interim relief available under Section 9 of the Act with emergency arbitration.

How long it takes to obtain interim relief?

For the purposes of this study, we randomly selected 300 Section 9 applications filed before the Delhi High Court in the year 2016. Next, we excluded those applications that were either withdrawn or granted with the consent of the parties. For the applications that remained in our dataset, we analysed the time it takes to obtain the first ad-interim order. Ad-interim orders are orders of Indian courts that are operative either till the final disposal of an interim application or till the next hearing. For example, in urgent matters, a court might grant an ad-interim injunction restraining the respondent from calling upon a performance bank guarantee, pending the final adjudication of the Section 9 application. Accordingly, in evaluating the efficacy of Section 9 proceedings, the relevant time period is between filing of Section 9 application and grant of the first ad-interim order, as opposed to the date on which the Section 9 application is finally disposed of.

The study revealed that the median time it took the Delhi High Court to grant ad-interim relief from the date of filing is 3 days.

In the context of emergency arbitration, it is not possible to carry out a similar empirical study because arbitration institutions do not disclose data about individual cases. Also, time periods set out in the rules of the various institutions vary. For example, SIAC Rules provide that the emergency arbitrator must issue an award/order within 14 days of his appointment, while the ICC Rules provide 15 days. Experience shows that SIAC and ICC emergency arbitrators often issue their orders more quickly than that; nevertheless, it is likely to remain the case that parties can receive even quicker relief by filing a Section 9 application in Indian courts.

Success rate

Out of the 300 Section 9 applications filed before the Delhi High Court, 72 applications were either granted, withdrawn by consent or remain pending with no interim relief ordered to date. Of the remaining 228 applications, interim relief of some sort was granted in 167 cases. This represents a success rate of 73 per cent for the applicant. The most common forms of interim relief granted by the Delhi High Court were freezing injunction prohibiting dealing with or disposing of certain assets, orders for deposits of sums in court, creation of bank guarantee in favour of the applicant, and disclosure of assets.

In case of emergency arbitration, again very limited data is publicly available to evaluate the success rate in a methodical manner. In case of SIAC for example, between July 2010 and 31 March 2017, 57 emergency arbitration applications were filed, of which 29 applications were granted while 2 remain pending, 6 were withdrawn and 4 were granted by consent. That represents a success rate of 64.4 per cent. Other institutions have not however published similar statistics.

Orders against third parties

Emergency arbitrators cannot grant relief against third parties. That is an important limitation, which derives from the fact that the jurisdiction of emergency arbitrators and the (eventual) arbitral tribunal is limited to those parties who have consented to submit their dispute to arbitration. For example, article 29(5) of the ICC Rules expressly provides that the ICC’s Emergency Arbitrator Provisions apply only to signatories to the arbitration agreement or their successors.

On the other hand, Indian courts, like courts of other jurisdictions, can grant interim relief against third parties in certain circumstances (for example, where such orders are necessary to protect the subject matter of the arbitration). The classic situation is when a freezing order is granted against a bank that holds funds on behalf of one of the respondents. An emergency arbitrator would not be able to make the bank a party to the freezing order.

Ex-parte orders

The ability of a party to obtain ex parte interim orders can be crucial in circumstances where an element of surprise is necessary (for example, where prior notice to the respondent would lead him to remove his assets from the jurisdiction of the court). Like in other jurisdictions, Indian courts can grant ex parte orders in exceptional circumstances. Emergency arbitrators, on the other hand, cannot grant relief on an ex parte basis. That is because one of the central tenets of arbitration is that all parties be given equal opportunity to present their case.

Enforceability

Even if a party is successful in obtaining relief from an emergency arbitrator, it must still deal with the question of enforcement. With the exception of Singapore and Hong Kong, in no other country orders of emergency arbitrators have received statutory recognition. In India, the Law Commission considered this issue at the time of suggesting amendments to the Act; however, ultimately no such amendment was made. Therefore, orders of emergency arbitrators are not enforceable in India. The fact that certain rules permit emergency relief to be granted as “awards”, and not just “orders”, will make no difference to their enforcement in India (compare Schedule 1(6) of the SIAC Rules with Article 29(2) of the new ICC Rules).

Despite concerns regarding their enforceability in India, emergency relief can be crucial in Indian related arbitrations. To start with, orders of emergency arbitrators may be extremely helpful if the respondent has assets in jurisdictions where such orders are enforceable (e.g. Singapore and Hong Kong). Further, experience shows that parties often voluntarily comply with emergency orders. That may be because losing parties fear that arbitral tribunals would not look too kindly on their failure to comply with the orders of emergency arbitrators. Moreover, to further incentivize compliance, arbitration rules allow arbitral tribunals to reflect non-compliance with the orders of emergency arbitrators in their final award (see, e.g., Article 29(4) of the ICC Rules). Finally, and rather counter-intuitively, orders of emergency arbitrators may assist a party in obtaining relief from an Indian court under Section 9 of the Act (see, e.g., HSBC v. Avitel 2014 SCC OnLine Bom 102, where the Bombay High Court granted interim relief in the same terms as that of a SIAC appointed emergency arbitrator; but see Raffles Design (2016) 234 DLT 349, where the Delhi High Court in the context of a Section 9 application effectively ignored the orders of a SIAC appointed emergency arbitrator).

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.

Excellent research. Only proves India’s pro Arbitration stance. What about the Bombay High court?

Thanks Badrinath. We had collected data for the Bombay HC as well, but the results were off the mark so we decided to not publish them (e.g. the median time taken to get the first ad-interim order from Bombay HC seemed to be much longer than what our own experience shows). We are checking the data and might publish a separate article in the coming weeks.

Interesting results! On a side, Netherlands also provides statutory recognition to emergency arbitral relief, albeit without using the term “emergency arbitrator” (Netherlands Code of Civil Procedure, Arts. 1043b(2)).

Amazing and Helpful Research which clarifies a lot of conceptual questions.

In relation to the non-enforceable nature of the order passed by the emergency arbitrators could you please point to a particular precedent if any which would conclusively substantiate the statement.

Thank you for your comment Kalp. Yes, there is some precedent indicating the unenforceability of an EA award in India. We note that the Delhi High Court has held that “the emergency award passed by the Arbitral Tribunal cannot be enforced under the [Arbitration and Conciliation] Act and the only method for enforcing the same would be for the petitioner to file a suit” (paragraph 99, Raffles Design v. Educomp Professional Education ). Of course, filing such a suit would be a rather ineffective way to seek enforcement of the EA award. Hope this clarifies.

Thanks for such an insightfull article on section 9 of ACA,1996. Also after reading the article this land me to a query where in such 300 cases of delhi HC identified by does any of the case reported a problem of Due process, where the Respondant has argued that it has not been given a proper time to file a reply for the application of interim relief. ?