Efficiency in arbitration is an area that is discussed so often it almost feels inefficient to discuss it. Indeed, when the Australian Centre for International Commercial Arbitration (ACICA) (in conjunction with FTI Consulting, and with the support of the Australian Bar Association, Francis Burt Chambers and the WA Arbitration Initiative) launched the results of the inaugural Australia-wide arbitration survey, the Australian Arbitration Report (Report) on 9 March 2021, the primary intention was not starting a discussion focussed on efficiency in arbitration. It is the first empirical study of its kind on the use of commercial arbitration in Australia. The culmination of analysis of survey results yielded from information provided by 111 respondents, including data in relation to 223 unique arbitrations with an Australian connection comprising AU$35 billion in disputed value, a copy of which can be found here.

However, the data provides real insight into how Australian parties, arbitrators, legal representatives and companies with Australia-based projects are conducting arbitrations, drafting arbitration agreements, and their sentiments about arbitration. It is clear from the Report that many factors affect the overall efficiency of arbitration, and in turn, users’ sentiment of the arbitration process. The conclusions drawn from the Report and this article are not limited to Australia – they can apply to other jurisdictions.

Australian arbitration – increasing the regional focus

At the launch of the survey’s results, the Honourable Amanda Stoker, Assistant Minister to the Attorney General of Australia, noted the developments leading to Australia becoming an attractive seat for international arbitration in the Asia-Pacific region. The Report indicated that many of the users of arbitration with an Australian connection recommend seating their arbitrations in Singapore, London, Hong Kong and Australia, in that order. While some of this preference might be due to Australian-connected parties desire to choose a neutral seat, it may also be part of what is often called the ‘tyranny of distance’ that Australia faces due to its location.

The increased use of technology and virtual hearings arising out of the COVID-19 pandemic is enabling Australia to overcome this ‘tyranny of distance’. Together with Australia’s newfound accessibility, as Minister Stoker said, the Report highlights that ‘geopolitical developments have provided a pathway for Australia to increase its profile in the Asia-Pacific region’. Not only will the opportunity for Australia to better engage with its regional neighbours have a profoundly positive impact on its status as an attractive seat for international arbitration, it would also allow specialisation of Australian arbitration users in disputes of this kind.

The type of case – a key element of efficiency

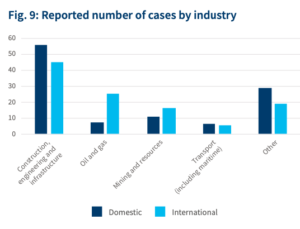

The type of disputes most prevalent in Australia is likely influenced by the fact that Australia and some neighbouring nations have natural resources that are located at a distance from ports, requiring large construction projects to access them. As a result, the profile of Australian cases is often thought to be construction and engineering focussed. This is reflected in the data, with construction cases accounting for almost half of all the arbitrations reported by the respondents. However, the Report’s data reinforces the prevalent status of oil and gas, mining and resources, and transport expertise (Fig. 9).

Separately, the data shows that arbitration in the oil and gas industry consists of a relatively small number of cases with large values in dispute, while arbitrations in the construction industry consist of a relatively large number of cases with relatively smaller amounts in dispute.

For these disputes, parties with an Australian connection are using institutions and rules that are both global, like the ICC (~ $10 billion AUD) or UNCITRAL rules (~ $9 billion AUD), or more regional such as SIAC (~$8 billion AUD), ACICA (~$2 billion), HKIAC (~$1 billion AUD).

The characteristics of the arbitrations are important because they help to frame how parties and arbitrators conduct their disputes. The institution administering the dispute may have an effect on the composition of the tribunal. Parties are influenced in how they run their dispute by the value (either monetary or otherwise). Certain industries have higher value disputes (among these being construction, oil & gas, which are both prevalent in Australia and the region).

The arbitration process – the effects of matter size

One of the outcomes that we learned from the Report was the relationship between mediation and settlement. The propensity to settle appears to correlate with the amount in dispute, whereby the probability of settlement substantially dropped as matters approached AU$100 million in disputed value. As there was a limited subset of data, the tendency of matters with smaller amounts in dispute to settle does not necessarily correlate to matters that are conducted through a mediation process having a greater likelihood of settlement. However, the data showed that mediation during the arbitration process did not correlate to settlement.

When parties did reach the award, for the most part, these awards were satisfied, at least partially.

Similarly, the Report indicates a correction between value of dispute and number of hearing days (with the average number of hearing days being less than two for a dispute worth $500,000 AUD, and an average of 15 for disputes worth $500,000,000 AUD. The number of hearing days correlates to costs, both tribunal costs, and external legal costs (which, according to the Report, account for almost half of the costs of arbitration). All of these factors are heavily influenced by who has been appointed as arbitrator.

Tribunal composition – the Tribunal’s influence on proceedings

Some of the respondents commented in the survey that they felt that the pool of arbitrators was too shallow. Additionally, respondents indicated that they chose arbitrators based on previous experience, familiarity, and reputation.

The Report also highlighted the room for improvement for diversity in arbitration, particularly as regards female arbitrators. While the data revealed an overwhelming proportion of party appointments going to male arbitrators, institutional appointments were substantially more likely than party appointments to be female arbitrators. The survey did not cover other points of diversity.

This choice is likely linked to the value of the dispute and type of dispute. The higher the value of dispute and or amount of factual analysis required, the more likely there will be numerous witnesses (expert and lay), thereby creating a longer hearing. The value in dispute will also make parties consider arbitrators with certain experience levels who they think can handle the voluminous material and complexity. Many of these arbitrators may be experienced in subject matter areas or be experts in legal analysis rather than arbitration procedure itself. If an arbitrator is not as familiar with the flexibility and options available within arbitration, then the choice in arbitrator likely impacts the length and cost of the overall proceeding.

User sentiment and the reasons why arbitration is chosen

Interestingly, the freeform comment field in relation to common complaints with arbitration indicated that arbitration too often resembled litigation. By participating in such proceedings, respondents were losing one of the key values, flexibility, which they felt arbitration added.

This sentiment is consistent with the circumstances in which arbitration is chosen by users with an Australian connection. The Report indicated that respondents view the key benefits of arbitration to be enforceability, confidentiality, and flexibility (in that order). Arbitration has provided parties the autonomy to choose how and with whom they resolve their disputes, tailoring procedures to their requirements without compromising the fundamental principles of due process, natural justice, and finality. However, if the proceedings were more flexible and less expensive, then these factors might not have been as low on the list on why arbitration was chosen in the first place.

Conclusion

The Report indicates that the issue of efficiency is one that spans the entire process of arbitration and is influenced not just by the choices parties make (eg how they run their case, who they choose as arbitrator) but also the market within which they operate.

What is incumbent upon arbitration practitioners is to search for efficiency in every matter that they are involved in: to try to minimise costs, encourage settlement and choose the right arbitrator for the dispute.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.

This Report revealed some dynamic correlations between factors influencing the arbitral process. However, I believe that the issue of diversity could have been explored deeper. For instance, it would be useful to examine if and how the amount or type of a dispute affects the choice of male or female arbitrators. An answer to this question could be a starting point for the establishment of diversity in arbitration, which remains a serious impediment.