On 21 April 2021, the CIArb’s London Branch hosted its annual Keynote Speech, which was held online this year. In her speech on “The Proper Law of the Arbitration Agreement”, Professor Dr. Maxi Scherer discussed the different approaches taken by jurisdictions worldwide in determining the law governing the arbitration agreement. She further compared those approaches against the solution adopted by the U.K. Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Enka v. Chubb [2020] UKSC 38 (“Enka”). Professor Scherer also unveiled her recent comparative research—discussed below—on the different approaches followed in 80 jurisdictions worldwide for determining the proper law governing the arbitration agreement, highlighting the lack of a clear, uniform answer to this fundamental question. Professor Scherer noted that, historically, Article V(1)(a) of the New York Convention favors the law chosen by the parties or the law of the seat (in the absence of the parties’ agreement) as the applicable law to the arbitration agreement. However, diverse interpretations and applications of this article have resulted in a lack of a harmonized, uniform approach.

The Approach Adopted in Enka for Determining the Proper Law Governing the Arbitration Agreement

Enka was a subcontractor for the construction of a power plant in Russia. The applicable contract contained an arbitration agreement for ICC arbitration with its seat in London but did not specify the law governing the arbitration agreement. Furthermore, the parties’ contract did not expressly prescribe the governing law for the contract itself. Following a fire at the power plant in 2016, Chubb paid out US$400 million in respect of damage caused by the fire to its insured, the other party to the Contract. Chubb asserted that it was subrogated to the counterparty’s claims and sought to recover from Enka in the Russian courts regarding the sums Chubb had paid out, arguing that Enka’s defective works had caused the fire.

Against this background, in 2019, Enka made an urgent ex parte application for interim relief to English courts, seeking a declaration that Chubb was bound by the arbitration agreement which covered Chubb’s claims. The English Court of Appeal concluded that the arbitration agreement was governed by English law based on the parties’ choice of London as the seat for their arbitration. On this ground, the Court decided that the parties had impliedly chosen that the arbitration agreement is governed by the law of the seat, i.e., English law.

By a majority of 3-2, the Supreme Court upheld the Court of Appeal’s conclusion that the arbitration agreement was governed by English law but departed from its reasoning on that same issue. The Supreme Court found the parties have neither expressly nor implicitly chosen any law to govern the arbitration agreement. Applying the closest connection test, the Court concluded that this test led to applying the law of the seat, i.e., English law.

Professor Scherer noted that the Supreme Court further outlined several broader directions regarding the law governing arbitration agreements. First, where parties have expressly selected a specific law, that law will govern the arbitration agreement. Second, where parties have not selected any laws regarding the contract or the arbitration agreement, the fallback is the closest connection test, i.e., the seat of the arbitration. The third situation is where parties have chosen the seat of the arbitration and the law governing the contract but omitted the selection of the law governing the arbitration agreement. In that case, the presumption is that the law governing the contract will also apply to the arbitration agreement. This presumption is not displaced in favor of the seat by the mere fact that parties have chosen a seat somewhere else. (Enka ¶170)

However, the Supreme Court outlined two exceptions to this presumption. The first exception is when the lex contractus invalidates the arbitration agreement—the principle of validation. Thus, if the lex contractus leads to the invalidation of the arbitration agreement, the presumption is displaced in favor of the seat. The second exception applies if “any provision of the law of the seat which indicates that, where an arbitration is subject to that law, the arbitration [agreement] will also be treated as governed by that country’s law.” (Enka ¶170) Here too, the presumption is displaced in favor of the law of the seat.

Professor Scherer commented that the solution adopted by the Supreme Court yields a complicated process. This complication arises when parties have chosen a seat for their arbitration and a law governing their contract different from the seat. In such circumstances, the English judge will need to ascertain the content of two foreign laws, under the two exceptions above, to determine the law governing the arbitration agreement.

Comparative Research on the Different Approaches Taken by Jurisdictions Around the World to Determining the Law Governing the Arbitration Agreement

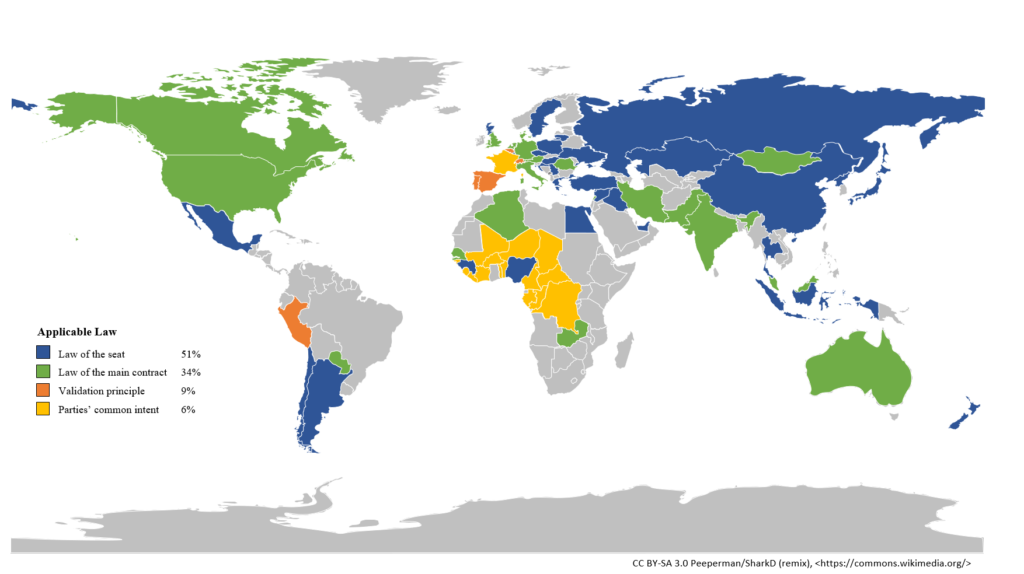

Professor Scherer’s comparative research tests the Supreme Court’s suggestion in Enka that international authorities favor the lex contractus approach in determining the proper law governing the arbitration agreement. The underlying factual hypothesis of the map below is the case where parties expressly have selected the seat of the arbitration and the law governing the contract but have not selected the law governing the arbitration agreement specifically. In such cases, courts in 80 jurisdictions have adopted different solutions.

Analyzing this map, Professor Scherer made several comments:

First, comparative analysis shows no majority view at the international level for the lex contractus approach (colored in green on the map), contrary to what seems to have been suggested by the Supreme Court in Enka. The map shows that 51% of the countries favor the law of the seat, compared to only 34% favoring the lex contractus.

Second, major arbitration jurisdictions (including England, France, Switzerland, and the U.S.) are divided as to which approach to take in determining the proper law governing the arbitration agreement. Notably, none of these popular jurisdictions adopt the majority approach of the law of the seat. While England and the U.S. apply the lex contractus approach, Switzerland and France apply the validation approach and an a-national approach, respectively. Overall, the data shows that there is no clear preference for any given of the four approaches.

Third, concerning the French a-national approach (colored in yellow on the map), Professor Scherer explained that its main advantage is the direct application of international principles by analyzing the common intent or will of the parties. Under this approach, absent an express choice of law by the parties, there is no need to analyze what laws govern the arbitration agreement. In Professor Scherer’s view, there are two significant problems with this approach. First, this approach leads to important uncertainty regarding the validity of the arbitration agreement. Beyond the statement of looking into the common intent or will of the parties, it is unclear what would happen if the parties’ common intent itself is unclear. Second, whether this approach can even be called an approach of international principles since this approach was shaped by, first and foremost, the French courts.

Fourth, regarding the Swiss validation approach (colored in orange on the map), Professor Scherer prized this approach as a well-established principle of interpretation in many countries. However, the main problem with this approach is that it cannot provide a solution to all questions relating to the arbitration agreement (such as validity, both formal and substantive, scope, interpretation), all of which are required to determine the law governing the arbitration agreement. Nonetheless, this approach works well for the validity of the arbitration agreement. It allows us to choose from the relevant laws (law of the seat, lex contractus, lex fori), the law that leads us to the validity of the arbitration agreement.

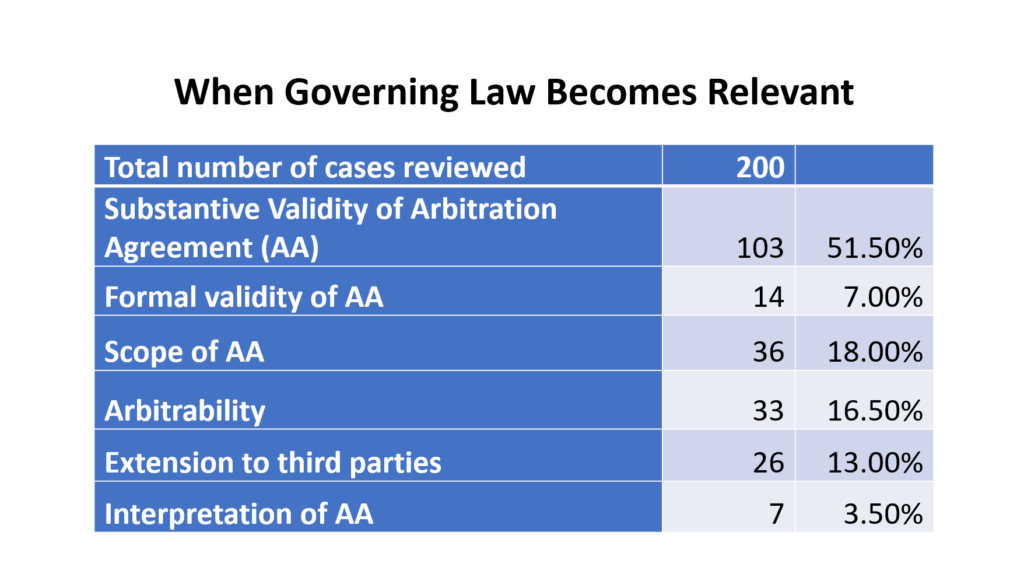

Fifth, Professor Scherer further mentioned that another part of her comparative research indicates most case law deals with questions of determining the proper law of the arbitration agreement deal with formal or substantive validity of the arbitration agreement.

The table below represents 200 published court decisions worldwide that deal with the law governing the arbitration agreement. (These are randomly selected decisions from approximately 30 jurisdictions. The data does not include arbitral tribunals’ decisions.) The results in the table show the underlying issue that triggered the question of the law governing the arbitration agreement. Notably, around 60% of cases deal with substantive or formal validity of the arbitration agreement when determining the law governing the arbitration agreement. This figure indicates that in most cases where the question of the governing law comes up, the validation approach helps to find a meaningful solution.

In conclusion, it is extraordinary that there is much uncertainty globally regarding this fundamental question of the proper law governing the arbitration agreement. One way out of this uncertainty could be applying Article V(1)(a) of the New York Convention. The solution provided by this article is straightforward and also eliminates and evacuates some of the current existing uncertainties.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.