In 2019 – 2020 a group of Ukrainian arbitration practitioners set out on an ambitious study of Ukrainian court decisions on recognition of arbitral awards. In this blog post, members of the group describe the background and methodology of the study and, most importantly, share its results.

Ukraine as an Arbitration Jurisdiction

Ukrainian law incorporates a ‘minimum set’ of international arbitration instruments. Ukraine is party to the New York Convention and its International Arbitration Law is nearly a verbatim translation of the UNCITRAL Model Law (1985 version). Ukraine also has its own international arbitration centre – the International Commercial Arbitration Court at the Ukrainian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, with a solid annual caseload and focus on international commerce.

In 2017, Ukraine significantly amended the procedural rules governing arbitration-related matters (“2017 Reform”). All recognition and enforcement cases are now heard by two courts: the Kyiv Appellate Court (as a first instance court) and the Supreme Court (as a court of appeal). No third level of review (cassation) is available. This model was designed to make proceedings quicker and focus arbitration-related expertise at these courts.

However, the legal framework is only as good as its practical application by courts. And objective data to assess Ukrainian courts’ efficiency and adherence to the internationally accepted standards was quite scarce and sporadic.

To fill this gap, arbitration practitioners from several Ukrainian law firms established a Working Group (“Group”) under the auspices of the Ukrainian Arbitration Association with the aim of analysing recognition and enforcement cases decided between 2006 and 2020.

In 2021, initial results of the Group’s work were presented at the UAA Annual Arbitration Conference. We share the key findings in this piece.

Methodology and Limitations

The Group’s primary data source was the Ukrainian Unified State Register of Court Decisions (“Register”). All research was done manually due to lack of effective automatic filtering in the Register. The Group therefore used several keywords to locate the recognition and enforcement cases among of other decisions. A system of quality checks was established to ensure the maximum coverage of relevant decisions.

When the Register started to function in 2006-2009, the courts were less disciplined in submitting information to it. This may be the reason why the number of cases that were identified and included in the dataset in this period is relatively low. Therefore, the charts below usually group data for the years 2006-2009 together. In any event, given the considerable number of cases in the dataset, the Group does not believe that any missing decisions may significantly affect the findings.

The Group’s research only considered cases where the courts (1) accepted an application to recognise and give leave to enforce an arbitral award, and (2) reviewed it in substance and rendered a final judgement. This caught nearly 600 cases.

Findings

Case flow

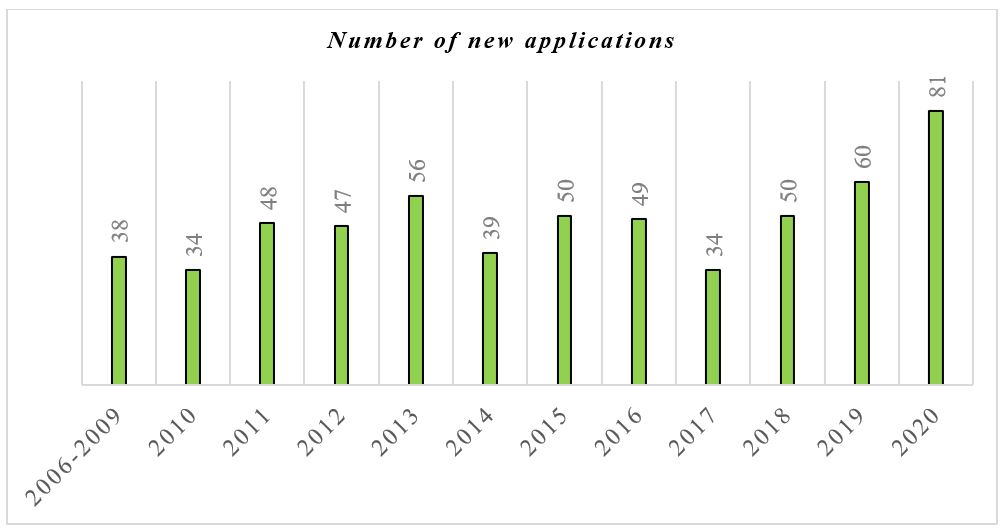

The number of applications for recognition and enforcement of arbitral awards fluctuated between 34 and 56 in 2010-2018. Years 2019 and 2020 showed noticeable spikes of 60 and 81 applications. The statistics appear to confirm a common perception among practitioners that the number of Ukraine-related disputes (including arbitrations) increased quite significantly after the 2014-2016 crisis in the Ukrainian economy.

Success rate

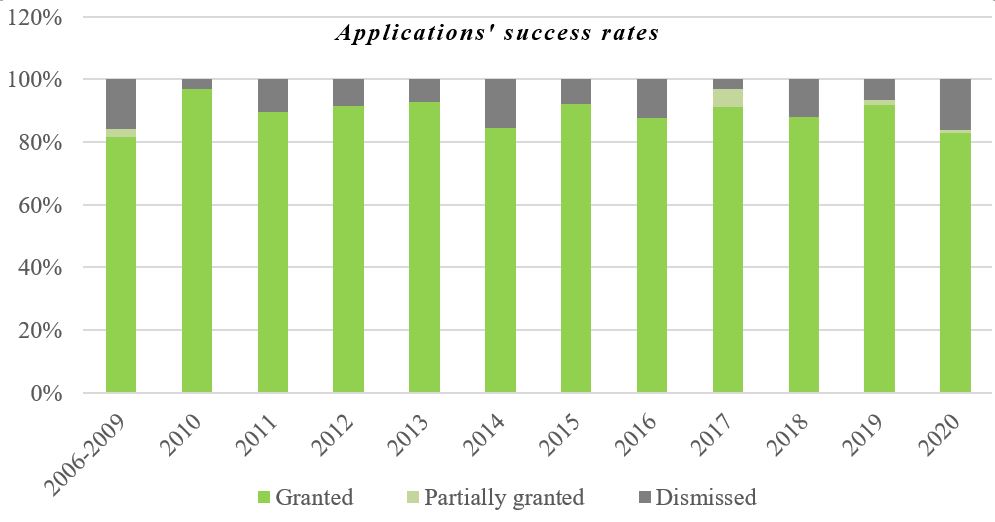

The annual success rates were fairly high, with an average of over 90%, reaching up to 97% in some years (2010, 2017).

However, to put this in context, we note that the Group considered only final decisions. Therefore, if, for example, the first instance court granted an application in December 2013, the court of appeal dismissed it in April 2014, and the court of cassation once again granted the application (upholding the first instance court decision) in January 2015, only the judgment of the cassation court would be reflected in the statistics for the year 2015.

This is important because an award creditor often had to go through several rounds of judicial review (with the lower courts potentially adopting a less arbitration-friendly approach) before getting the award recognised (the chances of which were still very high, as demonstrated by the success rates below). This was particularly so under the procedural rules in effect before 2017, which provided for three levels of review (as opposed to two levels now) and allowed the cassation court to remand the case for a new review to the lower courts.

Duration of proceeding and ‘anti-records’

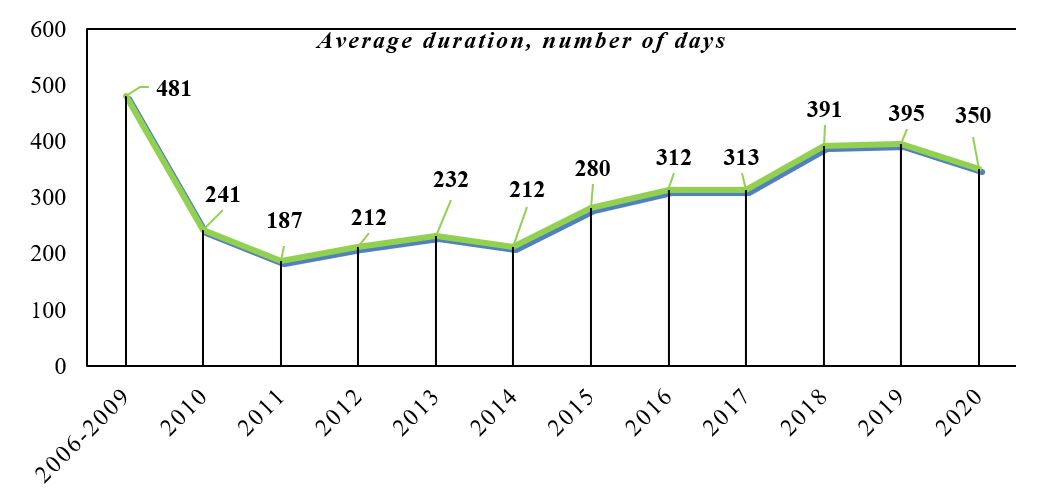

As with findings on the Success rate above, the duration is attributed to a given year based on the date of the final decision (e.g., if the case lasted for two years, from 2013 to 2015, the duration of this case will be recorded in the 2015 statistics).

Once again, the context is important for drawing conclusions from this data. The average, by its nature, combines the data of all cases, mixing those which were not contested and decided in two months, and those which were hard-fought and went through several court instances over several years. An average duration in most of the 2006-2020 period is less than a year. Only in cases finally decided in 2018 and 2019 the duration of proceedings slightly exceeded one year.

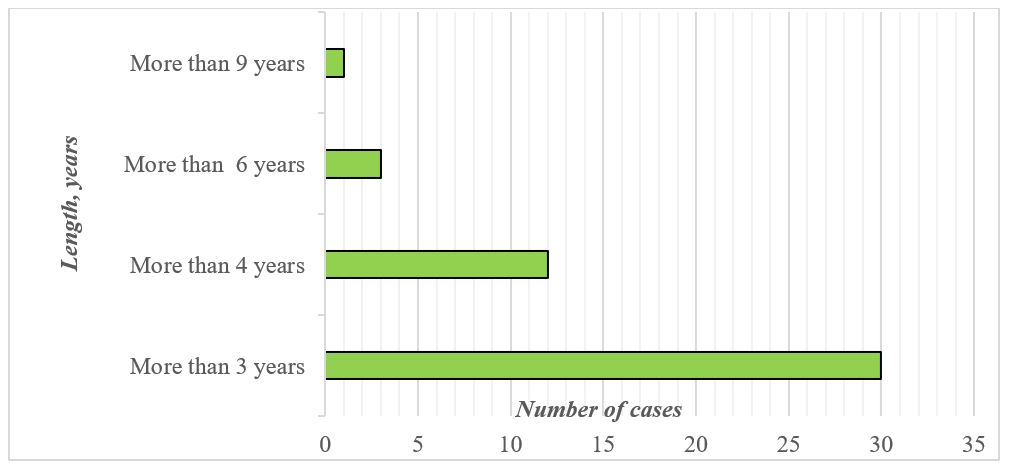

Despite the quite positive statistics, the Group also identified several record-breakers. These cases demonstrate how long the proceedings could have lasted in the worst-case scenario under the pre-2017 rules. Still, out of around 600 cases in the dataset, only 46 lasted over three years. The graph below shows the distribution of those 46 cases by length.

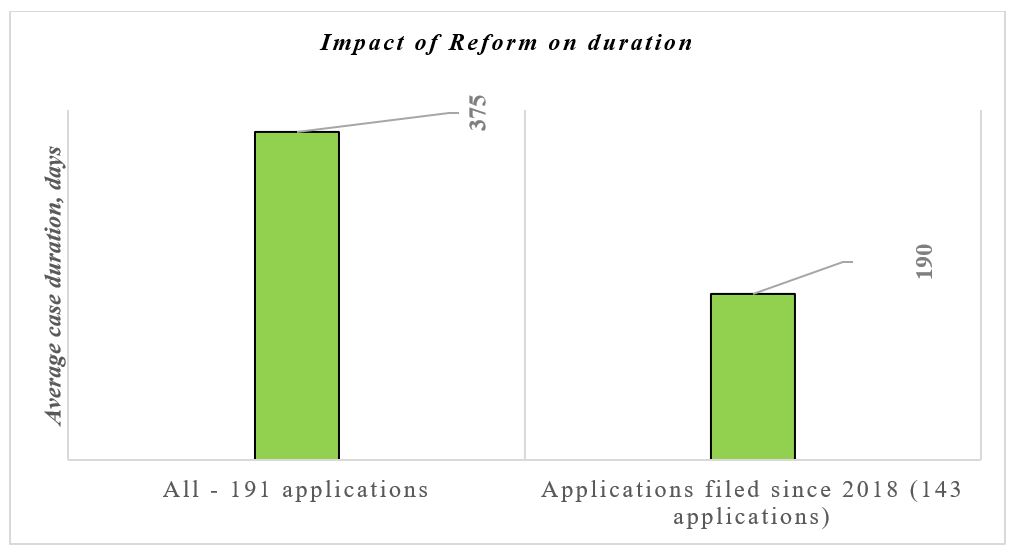

Finally, as we describe above, one of the key ideas behind the 2017 Reform was to increase the efficiency of recognition and enforcement proceedings. Naturally, the Group wanted to assess the 2017 Reform’s effects.

After the 2017 Reform, courts reviewed and rendered decisions on applications brought under the pre-Reform and post-Reform rules. It would therefore not be entirely correct to measure the Reform’s effect based on the total average duration of cases in 2018-2020. Therefore, we also looked separately at the cases that were filed under the new rules of procedure (since 2018).

The chart below compares the average duration of all cases decided in 2018-2020 (191 cases) with the average duration of cases commenced under the post-Reform rules of procedure and decided in 2018-2020 (143 out of 191 cases). The difference of 185 days (375 – 190) speaks convincingly in favour of the 2017 Reform’s efficiency.

Grounds for refusal

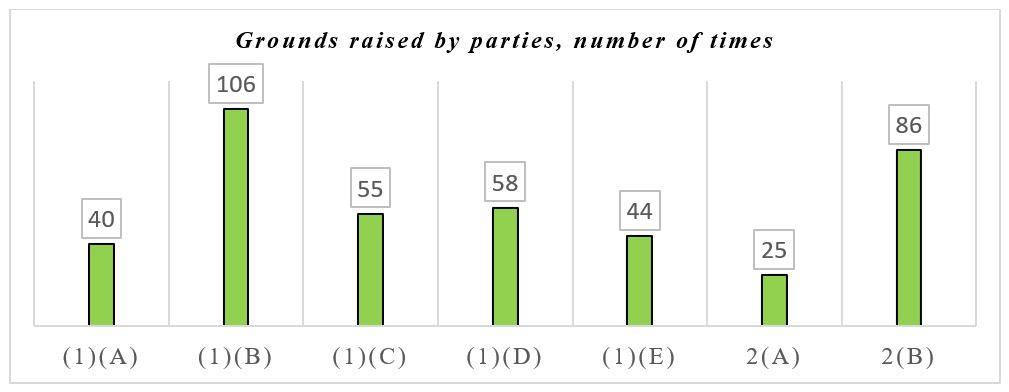

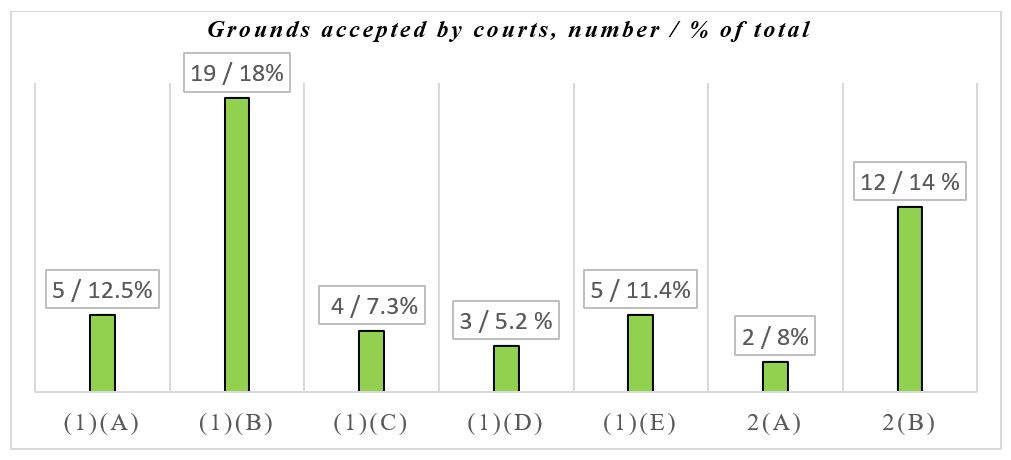

The Group sought to establish which grounds for refusal of recognition and enforcement under Article V of the New York Convention were ‘most popular’ (since it was not possible to discern raised and applied grounds in each and every case, the charts below may be less representative than other charts in this post).

The first chart shows that lack of proper notice (V(1)(b)) and public policy (V(2)(b)) are the two most popular grounds among litigating parties, while arbitrability (V(2)(a)) received the least attention.

The second chart confirms that it is quite hard to persuade Ukrainian courts to accept any of the Article V grounds. For instance, out of 86 times public policy was pleaded, only in 12 decisions (or 14%) did the courts dismiss the application based on it. Importantly, lack of proper notice is the most ‘dangerous’ ground for refusal under Article V – both in terms of how often this ground is invoked and how likely it is to succeed. This is an alert to any party that is likely to get involved in a Ukraine-related arbitration.

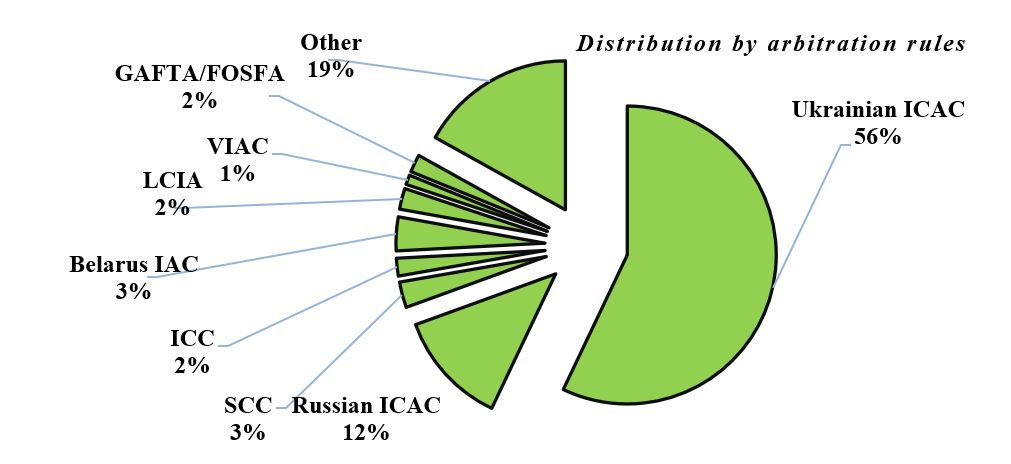

Most popular arbitral rules

Finally, the Group analysed the dataset to establish under which arbitral rules the awards considered by Ukrainian courts are commonly rendered. Ukrainian ICAC dominates the field, accounting for 56% of the awards. Russian ICAC and Belarus IAC are second most common, with 15% in total. The third biggest group are western arbitral institutions, with LCIA, ICC, VIAC, SCC and GAFTA/FOSFA together accounting for 10%.

Conclusions

Although the dataset is still being analysed, there are already a lot of helpful findings. Analysis reveals that Ukrainian courts’ average rate of granted applications for recognition and enforcement is over 90%. Furthermore, the study showed an average duration of cases and allowed us to trace the first positive effects of the 2017 Reform. The elimination of cassation review and transfer of all cases to the Kyiv Appellate Court seems to have decreased the average duration significantly.

These findings will be helpful for practitioners assessing prospects of bringing an arbitral award before Ukrainian courts (and to those who are about to commence Ukraine-related arbitration) and increase positive perception of Ukraine as an arbitration-friendly jurisdiction.

We are looking forward to monitoring future developments in Ukrainian arbitration-related case law. Stay tuned!

=======

Special thanks go out to all members of the Group: Serhii Uvarov, Zoriana Matiiash, Mykola Krys, Oleksii Maslov, Dmytro Izotov, Kristina Mysenko, Alina Danyleiko, Olexander Droug, Olesia Gontar, Serhii Yaroshenko, Oksana Varakina, Maksym Khitrykh, Viktoria Ivasechko, Anastasia Polishchuk, Iryna Vivcharyk, Olha Nosenko

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.