On 22 February 2024, I am pleased to deliver the 6th ADR Address of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, co-organised by the Australian Disputes Centre. Past lecturers have been senior former or serving Australian judges, with some discussing developments in arbitration. More widely, there has been quite extensive discussion on case law and commentaries, including on this Blog, about the relationship between international commercial arbitration (“ICA”) and international litigation conducted through courts, as part of an overall system for resolving cross-border commercial disputes (see e.g., here and here).

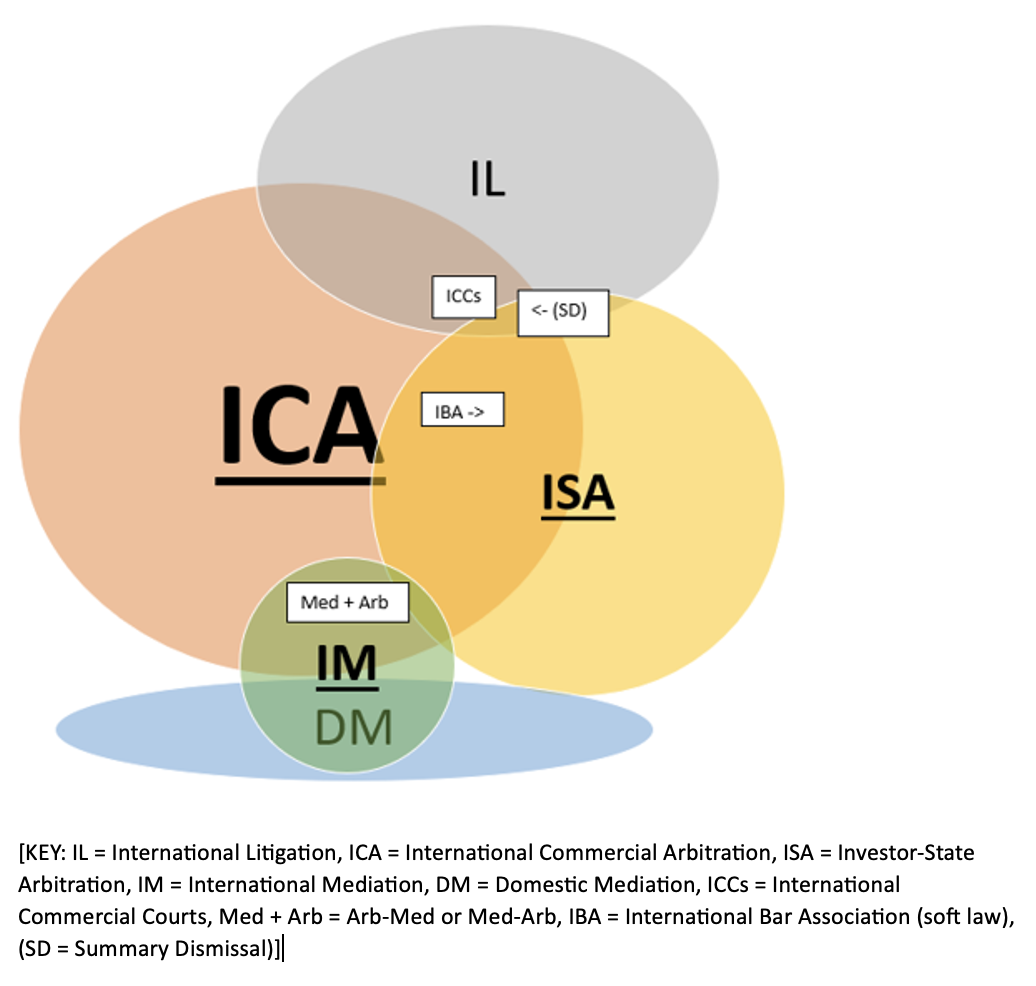

My address will take an even more encompassing view (and will be available as a full paper here after the public lecture). It teases out some connections or influences among ICA, investor-State arbitration (“ISA”), and international and domestic mediation, which I have also sought to represent visually in the graphic below. Part 1 proposes that such cross-fertilisation may be or become more or less productive, particularly from the perspective of reducing costs and delays. Those problems have constituted another persistent theme on this Blog, as evidenced recently by the interview with The Hon Wayne Martin AC KC and outline of the draft 7th Edition of the SIAC Arbitration Rules.

My address will begin by charting how international arbitration generally has burgeoned, especially since the 1990s, including across the Asian region (Part 2). The growth originated mainly in ICA, but it has been bolstered especially over the last 10-15 years by mostly now treaty-based ISA.

However, as in the 1990s, concerns are again surfacing about escalating delays and especially costs (Part 3). Burgeoning costs and delays are due not just to the growing complexity of transactions, and therefore the underlying disputes. Other contributing factors include:

- international arbitration still having no real competitors for cross-border dispute resolution (express choice of an international commercial court as forum and the 2019 Singapore Mediation Convention ratifications remain few, while the EU-style investment court alternative to traditional ISA has not yet caught on);

- the expansion of large law firms and the ‘billable hours’ culture (which can disincentivise early dispute settlement);

- conservatism among arbitral institutions and practitioners about controlling legal costs (e.g., via caps on lawyer fees claimable, or ‘sealed offers’ incentivising early settlements);

- the double-edged sword of confidentiality (potentially allowing arbitrators to be more robust and succinct in rulings, yet exacerbating information asymmetry in the markets for arbitrator and especially counsel services); and

- the proliferation of soft law instruments particularly from the International Bar Association (promoting harmonisation but also formalisation of procedures, with more civil law tradition-inspired competitors like the 2018 Prague Rules struggling to gain traction).

The Fall of Arb-Med

In addition, cross-fertilisation from mediation practice has not yet borne much fruit globally in the form of hybrid Arbitration-Mediation (“Arb-Med”), whereby parties authorise arbitrators themselves to act as mediators (Part 4), in ISA, and even in ICA. As ICA spreads East from the 1990s, the practice of the arbitrator acting as mediator attracted interest (notably, still, in mainland China) due to the potential efficiencies. Yet concerns arose especially if the same neutral engaged in ‘caucusing’, due to fundamental principles of neutrality and equal treatment of the parties.

This led to Hong Kong in 1989 and Singapore in 1994 adding to their UNCITRAL Model Law-based legislation that if mediation fails, the arbitrator must disclose material information received in confidential caucusing. This was not popular in practice. So instead, from 2015, the Singapore International Arbitration Centre and the Singapore International Mediation Centre developed an Arb-Med-Arb protocol involving separate processes and neutrals, which has attracted a few dozen cases.

In New South Wales, a 1990 amendment to the Commercial Arbitration Act (“CAA”) allowing parties to consent to Arb-Med was also hardly used. So, a revised provision was introduced into the CAA, re-enacted Australia-wide from 2010 (based otherwise now on the Model Law, only for domestic arbitrations). It added to the Hong Kong approach, a requirement for the parties to give a second consent for the neutral to revert to arbitration if the agreed mediation attempts failed. This too seems to be rarely used, perhaps because a respondent can delay proceedings by withholding the second consent. The draft ACICA Arbitration Rules proposed this type of Arb-Med, including the appointment of a “back-up arbitrator” to streamline that eventuality, but the proposal did not gain enough traction in public consultations (for further information, see e.g., here).

Japanese legislation and the main Japanese Commercial Arbitration Association Rules now provide that parties must give clear consent to Arb-Med, and some practice remains of parties further agreeing that the neutral will not use material information in the award. But Arb-Med is not actively advertised there, nor in Korea or Taiwan.

The Rise of Med-Arb

Instead, Mediation-Arbitration (“Med-Arb”) and other multi-tiered dispute resolution clauses are becoming more prevalent in cross-border transactions, aiming to reduce the costs and delays associated with proceeding to international arbitration (Part 5). However, the spread has not been uniform across the world of ICA, especially it seems in parts of Asia. Med-Arb clauses are less commonly agreed to by parties from Korea, Japan, and China, for example, than by those from some common law jurisdictions in Asia. An explanation may be that more litigation costs and lawyers in the latter lead the courts and legislatures to promote ADR domestically, so commercially supplied mediation services and familiarity grow – eventually spilling over into cross-border contracting and dispute resolution. The relative paucity of Med-Arb clauses in cross-border contracts involving parties from some parts of the world may also help to explain the relatively few ratifications of the 2019 Singapore Mediation Convention.

The overall growth in Med-Arb provisions in ICA has not yet had much impact on investment treaties and therefore on ISA. However, a few treaties do now provide for mandatory mediation before arbitration.

In addition, cross-fertilisation partly from ISA regarding the consequences of non-compliance with pre-arbitration steps in such clauses is causing complications, although it may lead to constructive solutions in ICA as well as ISA. Until a decade or so ago, a major concern of courts faced with Med-Arb clauses or negotiation-then-arbitration clauses in commercial contracts, especially in common law jurisdictions, was whether the negotiation or mediation obligations were sufficiently certain to create contractual obligations. Most now answer more affirmatively (see e.g., here).

The current question has instead become: does compliance with the pre-arbitration step go to the jurisdiction of the tribunal, or the admissibility of a claim? If the former, compliance is a pre-condition to the arbitration, and non-compliance could lead to award annulment. If the latter (the emerging preferred view in ICA circles, as earlier in ISA), tribunals permitting non-compliance and admitting claims in arbitration would be making an error of law, but this is usually then not reviewable by courts. This tends to be lauded by commentators as more “pro-arbitration”.

However, it could also be criticised as “anti-ADR” because the admissibility approach suggests that compliance with the mediation or other steps is not seen as so important in that legal system. My paper suggests that we may need a nuanced approach, depending not just on the wording used by the parties in their multi-tiered dispute resolution clauses. Other factors to consider are the types of pre-arbitration steps chosen, when this issue arises (e.g., regarding stays of litigation in favour of arbitration, compared to later award challenges), and how widespread and familiar the ADR practice happens to be in the relevant jurisdiction.

Overall, therefore, various crossovers are already evident among ICA, ISA and international mediation. Such cross-fertilisation, and other examples like the spread from ISA into ICA of provisions on summary dismissal, should be tracked and channelled into the most productive interactions.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.