What happens when an arbitrator refuses to answer fundamental questions about their impartiality that only they can address? Questions like, “Have you received any promises or gifts from any of the parties: Ms Aphrodite, Ms Hera or Ms Athena?” or even “Do you have any interest in or connection to Ms Helen, a person associated with one of the parties?”

Our case is a modern loose adaptation of the Greek classic “The Judgment of Paris” (see here). Suppose a party to a multi-party arbitration posed these oddly specific questions to Paris, our mythical Sole Arbitrator. The questions are few but precise, some touching on scenarios outlined in the IBA red list. They would have been answered in most arbitral institutions’ questionnaires. All referred to true scenarios that, if Paris were to disclose, could cause his removal and annulment of his past partial awards. So, what if Paris refuses to answer? He neither discloses nor denies the underlying facts suggested by the questions. On the contrary, he states that those are private matters. None of the parties’ (or the court’s) business.

His refusal and subsequent behaviour are suspicious. The matters are subject to mandatory disclosure under the applicable law and arbitration rules, but how can this be enforced? This situation raises questions about the nature of the “duty to disclose” and how we think of it. Could Paris be removed, or his awards annulled, for refusing to talk?

Hard Law, Soft Teeth: The Mainstream Interpretation

While most national laws assert that arbitrators have a duty to disclose, making it hard law, courts and doctrine treat it differently. Typically, when this issue reaches national courts, one of the parties has already uncovered and proved something about the arbitrator. The pattern is the same: Hera or Athena (leaving aside their own attempted briberies) proves that Aphrodite bribed Paris, which Paris did not disclose. Then, the court, aware of both the underlying fact (“Aphrodite bribed Paris”) and the nondisclosure (“Paris did not disclose”), rules that the arbitrator acted with bias and breached his duty to disclose, possibly leading to the annulment of the award.

This is the scenario of the Halliburton (English Supreme Court), the García Armas (Paris Court of Appeal) and the Escho (Brazilian Superior Court) arbitrations, leading cases on the duty to disclose. The courts concluded that the failure alone does not have legal consequences. It is only significant depending on the undisclosed fact. This logic also applies to investment arbitration (see Tidewater or Eiser). So, we must first examine the undisclosed fact, determine if it disqualifies the arbitrator, decide whether to replace the arbitrator or annul the award, and only then think about the duty to disclose. The failure to disclose is secondary to analysing the underlying undisclosed facts in their context; it is an accessory to the primary decision.

This approach works when the underlying facts are known. However, it complicates matters in situations like Paris’ refusal to talk. If the failure to disclose cannot disqualify the arbitrator, Hera or Athena need proof of the underlying facts. But they cannot provide it; aside from Aphrodite (the perpetrator), only Paris himself can. He has a legal obligation to disclose, which is counterintuitively unenforceable by law. Consequently, withholding information protects his own position, leaving the parties no legal remedy. According to mainstream thinking, there is nothing anyone can do. He may refuse to disclose his relationship with Helen or Aphrodite, and nothing will happen. While derived from hard law, the duty to disclose would bite with soft teeth.

Arbitral Ethics, Politeness and Etiquette

Two issues arise here.

First, are we basing our knowledge of the “duty to disclose” on the right cases? The usual court cases dealing with the duty to disclose are factually quite limited. If a party has already discovered an incriminating fact (such as “Paris loves Helen”), what impact will the duty have on the case? The incriminating fact alone would motivate discussions about the award’s annulment or the arbitrator’s removal. In such cases, discussing the duty to disclose is secondary because, once facts are known, the duty ceases to be the central issue. Put another way, if Athena finds evidence that Aphrodite bribed Paris, she will likely fight over the bribe, not so much over his silence about it.

Similarly, as an instrument for transparency, wouldn’t the duty to disclose be better analysed when the underlying fact is unknown or unproven? In such cases, discussing a “duty to disclose” would serve a practical function. If Athena asks Paris, “Have you had unilateral contact with Aphrodite after your appointment as Sole Arbitrator?” and he responds, “This is private; I refuse to answer”, then fighting over transparency, breach of trust, and enforcing specific duties of candour would be the focus. Indiscriminately applying conclusions from the first scenario to the second does not make sense. Thus, the kinds of cases that have reached national courts may not be ideal for examining the duty in contexts other than their specific instances.

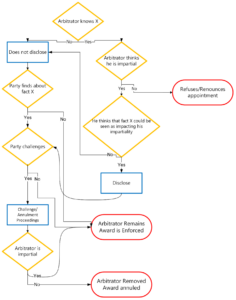

Second, what is the nature of this “duty”? If we take the mainstream interpretation of these court decisions seriously, the duty to disclose loses its legal force. What difference does it make to say that arbitrators have a legal duty to do X, Y, Z…n, if disobedience goes unchecked? Does it make sense to treat the “duty to disclose” as a legal obligation if the failure does not result in a legal sanction, such as removing the arbitrator or annulling their award? One could say it is still a legal obligation triggered by knowledge of the undisclosed fact. But this does not solve the problem. If the severity of the underlying fact independently (i) triggers the duty to disclose, and (ii) determines the legal consequence of the fact for the arbitration, (iii) then the failure to disclose is legally irrelevant. We created a decision tree of how this works.

Not only does the nondisclosure go unpunished, but it is also rewarded in practice. It adds an extra barrier (“party finds out about fact X”) between the arbitrator and the challenge. It could only be otherwise if the failure itself were legally sanctioned.

Whether a fact is disclosed or not, the consequences are the same. At most, the court or challenge committee can draw a positive inference from disclosure or a negative one from nondisclosure. Still, doing so reinforces our point. It interprets the (non)disclosure as a fact—another bit of behaviour from the arbitrator—not a hard legal standard.

The duty to disclose undoubtedly has an ethical component. However, this moral aspect alone carries no legal consequences. Through the mainstream interpretation, the duty to disclose may be an ethical, moral, communal, ideological, political (or …n) duty. The arbitration community enforces it sociologically and economically as a standard of arbitral politeness and reputation. But treating it as only this means it is a mere rule of etiquette: while your peers may disapprove and you might not be appointed again, the law will not intervene or affect your award for non-compliance. Paris walks free.

Conclusion: The Paradox of Disclosure and Its Two Routes

Let us say that our mythical arbitrator learns of a fact X that could compromise his impartiality. He has two options. The first is straightforward: if Paris believes X genuinely undermines his impartiality or thinks the parties cannot waive their right to challenge him based on X, he must refuse the appointment. The second option is more complex: if Paris considers himself impartial but recognises that X might reasonably cast doubts on his impartiality, he must disclose it. The “duty to disclose” arises only when the arbitrator believes in his own impartiality. If he does not, he has a duty to leave the case. Paradoxically, this means that all disclosures arise from a statement of impartiality.

Does this imply that all nondisclosures are signs of partiality? No, and this is where the wisdom of the Halliburton, García Armas and Escho rulings shines. They concluded that an award can only be annulled if there is proof of underlying partiality, which is not presumable solely from nondisclosure. They prevented the absurd conclusion that all nondisclosure shows partiality. We only point out that an arbitrator’s failure to clarify a fundamental matter known exclusively to them, which is not the issue these courts have encountered, violates the arbitrator’s duties in a different way.

Knowing this to be their goal, there are two routes to interpreting them and their consequences for nondisclosure.

First, you can take the traditional route and assert that all nondisclosure by itself has no legal consequence. This is possible, but it does require believing that the courts have vacated the duty’s legal value. You can embrace it as a moral duty, which is also fine. International arbitration has lots of them; after all, it is a reputation-based system. Etiquette matters. But remember that if arbitrators have no legal duty to disclose, they would have a right not to.

Alternatively, you can believe that an arbitrator’s unwillingness to be transparent and respond in good faith carries legal consequences. Ensure the questions are reasonable and relevant; no one wants more arbitral guerrilla. Then, the ball would be on the arbitrator’s court. The key is to realise that the logical opposite of “all” is not “none” but “not all”. Thus, you can still believe that not all nondisclosures indicate partiality while acknowledging that some, in certain circumstances, most certainly do.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.

you ask, What happens when an arbitrator refuses to answer fundamental questions about their impartiality that only they can address? To answer the question, usually the arbitrator is not empaneled if he refuses to answer the disclosure questons.

An Arbitrator cannot, in practice, disclose his or her life story every time. There has to be judgement. If he is challenged as to a matter, then he is entitled to be told why the matter might affect his behaviour ii the arbitration. A party may be fishing or trying to create thoughts in the Arbitrator’s mind in advance of the arbitration. Indeed, one can envisage questions designed to provoke the Arbitrators into withdrawing for no other reason but to delay the process. If a matter would not disqualify the arbitrator, disclosure might do no harm but is clearly beside the point – if there is any point.

This scenario o non-empanelment seems to imply an arbitration administered by an institution which has arbitrator disclosure rules. If I am not mistaken, the Halliburton v. Chubb case did not involve an arbitral institution issuing and/or enforcing such rules, which may differentiate it to some extent from certain other non-disclosure cases.

Legal, moral and ethical obligations involve elements of objectivity as well as subjectivity. It is debatable as to what exactly and how much personal-cum-professional information should be disclosed by arbitrators to preempt allegations of misconduct. Notwithstanding various rules, regulations and court judgments, there is always a possibility of at least few instances of either advertent and/or inadvertent non-disclosures. In each such case of allegations of partiality or bias, only the case-specific investigation can reveal the truth. Instead of waiting for the disaster to happen, it may be better for arbitrators to err on the side of caution by voluntarily disclosing anything and everything so that there is little scope for anybody to indulge in mudslinging. After all, there is no smoke without fire and virtue has its own rewards. Let the wise people be guided by their conscience.