Introduction

On 8 October 2018, the Ministry of Justice (the “MoJ”) of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (“Saudi Arabia”) announced that in the last 12 months its enforcement courts received a record-breaking 257 applications for enforcement of judgments and arbitral awards rendered outside Saudi Arabia, which were appraised at SAR 3.6 billion or “nearly one billion dollars.” Relevant issues of award enforcement in Saudi Arabia have been previously discussed in the Blog. The aim of this post is to provide a brief comparative summary of the applicable legal framework and an overview of the recent figures and developments pertaining to the foreign enforcement applications in Saudi Arabia.

Legal Framework

Saudi Arabia has acceded to the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (the “NY Convention”) in 1994. Unfortunately, the accession did not provide any relief to the level of uncertainty surrounding the recognition and enforcement of arbitral awards. In short, arbitral awards and all relevant documents still had to be translated into Arabic and submitted to the Saudi Board of Grievances (the “Board”). The Board would then perform a comprehensive review of the merits of the case to ensure that the award is in compliance with Shari’ah.

The infamous case of Jadawel International (Saudi Arabia) v Emaar Property PJSC (UAE) is a good, or perhaps slightly extreme, example of the interventionist approach adopted by the Board when conducting its review of the award. In its 2008 ICC award, the Tribunal dismissed Jadawel’s USD 1.2 billion claims and ordered Jadawel to pay Emaar’s legal costs. Upon review, however, the Board reversed the award and order Emaar to pay more than USD 250 million to Jadawel in damages.

In 2012, Saudi Arabia replaced its 1983 Arbitration Law (Old Law) that did not conform with modern arbitration practice with a New Arbitration Law, based on the UNCITRAL Model Law, by Royal Decree No. M/34 of 16 April 2012 concerning the approval of the Law of Arbitration (the “Arbitration Law”), which came into force on 9 July 2012. In the same year, Saudi Arabia enacted a New Enforcement Law by Royal Decree No. M/53 of 30 August 2012 concerning the Execution Law (the “Enforcement Law”), which came into force on 27 February 2013. The Enforcement Law was also complemented by Executive Regulations issued pursuant to the Minister of Justice Circular No. 13/T/4892 on 28 February 2013.

It is worth noting the following provisions of the New Enforcement Law:

- Article 1 defines an Enforcement Judge as the chief of the execution department and judges, execution department judge and the judge of the court who undertakes the duties of the execution judge, as the case may be.

- Article 2 provides the execution judge with the authority of forcible execution and supervision assisted by the sufficient number of execution officers pursuant to the provisions of the Law of Procedure before Shari’ah Courts.

- Article 6 states that all decisions taken by the execution judge shall be final. As a result, there is no appeal from the decision of the Enforcement Judge.

- Article 11 sets out the requirements for enforcing foreign judgments and arbitral awards. It provides that the Enforcement Judge may not enforce any court judgment and order passed in any foreign country except on the basis of reciprocity and after verifying the following:

1) the Saudi courts are not competent to hear the case in respect of which the court judgment/order/arbitral award was passed and that the foreign court/arbitration tribunal which passed it is competent in accordance with the international rules of jurisdiction set down in the laws thereof;

2) the litigants to the case in respect of which the judgment/award was issued were duly summoned, properly represented and were able to legally represent themselves;

3) the court judgment/arbitral award has become final in accordance with the law of the court/arbitration tribunal that passed it;

4) the court judgment/arbitral award is in no way inconsistent with any judgment or order previously passed by the Saudi courts; and

5) the court judgment/award does not provide for anything which constitutes a violation of Saudi public order or ethics.

The New Enforcement Law provides Enforcement Judges with enough teeth via Articles 46 and 47 to enforce the decisions. If the award debtor fails to pay the sum owed or fails to disclose property sufficient to satisfy the award within five days of notification of the execution order, the Enforcement Judge may impose a variety of sanctions some of which include travel bans, freezing debtor’s bank accounts, ordering the disclosure and seizure of assets, and event imprisonment.

One of the areas, where exercising extreme caution is advisable, is with respect to Article 11(5) of the New Enforcement Law requiring the Enforcement Judge to ensure an award does not contradict Saudi public order and Shari’ah. Apart from the obvious issue of the myriad of way in which Shari’ah may be interpreted, the author would also like to highlight the remaining difficulties in enforcement of an arbitral award that, inter alia, grants interest. It remains to be seen in what way an Enforcement Judge would treat such awards.

Arguably, the most important feature of the exceptionally fast processing of the foreign enforcement applications. Subject to any hearings and under normal circumstances, the Enforcement Judge should issue the execution order within one month of the application and, if necessary, order seizure of assets, freezing bank accounts and so on within another one-two months depending on the circumstances of the case.

Statistics

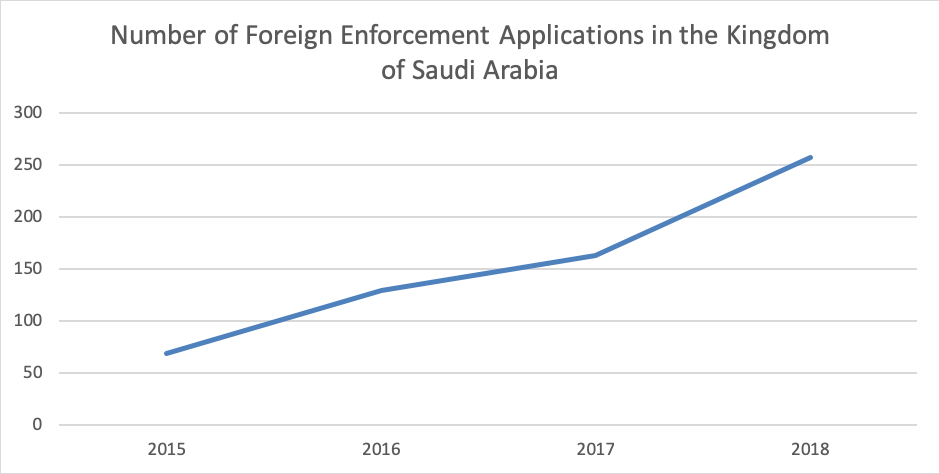

As a result of the data available on the MoJ’s website on the previous numbers and values of the applications for enforcement of foreign judgments and awards, the increase in the number of Foreign Enforcement Applications becomes apparent:

| Time Period | Number of Foreign Enforcement Applications | Total Value of Foreign Enforcement Applications (USD, approximate) |

| 25/10/2014 – 13/10/2015 | 69 | 639,408,000 |

| 14/10/2015 – 01/10/2016 | 129 | 1,145,606,000 |

| 02/10/2016 – 20/09/2017 | 163 | 666,050,000 |

| 21/09/2017 – 10/09/2018 | 257 | 959,112,000 |

| Total: | 618 | 3,410,176,000 |

In this regard, the author would like to offer three key takeaways with respect to the Foreign Enforcement Applications. First, the growth in applications year-on-year averages at 35%. Second, the total number of applications has now exceeded 600 with a total value passing the USD 3.4 billion mark. Third, more than 40% of the total number of application were made in the last 12 months.

Cases

Considering the absence of any statistics on the success rate of foreign enforcement applications in Saudi Arabia’s enforcement court, the author provides below some anecdotal enforcement examples identified mainly on the MoJ’s official website.

ICC Award (UAE subsidiary)

The first reported example of a successful enforcement of an arbitral award, pursuant to the Enforcement Law, came from an international law firm, on 31 May 2016. The development was also covered by a post on the Blog.

The Riyadh Enforcement Court (the “REC”) decided to grant the Foreign Enforcement Application made by a UAE subsidiary of a Greek telecommunications company against a Saudi data communications service provider. The ICC award in favour of the UAE subsidiary was rendered in London. The subsidiary managed to defend approximately USD 350 million-worth of counterclaims and was awarded approximately USD 18.5 million in its favour.

The arbitral award was obtained in late 2011 and, therefore, enforcement proceedings commenced with the Board. When it became possible, the subsidiary transferred the proceedings to the REC and, three months later, the award was recognised in Saudi Arabia.

US Court Judgment

On 16 May 2018, the MoJ informed of successful enforcement of a judgment rendered by a court in the US state of Virginia in favour of a US company against a Saudi tourism company in the REC. The judgment value was USD 3,758,000. It is not clear how long it took the REC to consider the US company’s Foreign Enforcement Application, but the Saudi company was ordered to pay the applicant within five days of the decision’s notification date.

Chinese Award

On 24 May 2018, the MoJ statement produced an example of award enforcement through an order a court in Jeddah. The court ordered a Saudi gold mining company to pay in excess of USD 10.1 million to a Chinese company thus enforcing an award issued by a “Chinese international arbitration tribunal.” Reportedly, the Jeddah court ordered the Saudi company to pay the award within five days of the decision’s notification date or “face the penalties in the country’s Enforcement Law.”

ICC Award (Malaysian company)

On 29 May 2018, the MoJ reported a new successful enforcement of the Foreign Enforcement Application at the REC. The REC enforced an ICC award in favour of a Malaysian company against a private Saudi university, which was ordered to pay the applicant USD 24,684,266, the award value, within five days of the decision’s notification date.

Other Examples

The MoJ has also cited enforcement of a foreign award ordering repayment of debts, which was issued in favour of Japanese companies against a Saudi company. Another shared example of enforcement proceedings relating to a Foreign Enforcement Application included “incarcerating the owner of a Saudi establishment for refusing to pay [approximately USD 636,000] to a Chinese company.”

Conclusion

Establishment of the Saudi Center for Commercial Arbitration in 2016 is a prime example of Saudi Arabia’s reignited interest in resolving disputes through arbitration, which is a vital element for attracting investments and ensuring that international commerce continues thriving in Saudi Arabia.

On the other hand, it is no less important for companies and individuals entering into business relationships with the residents and businesses in Saudi Arabia to be confident that a judgment or an arbitral award rendered by a court or a tribunal outside Saudi Arabia will be enforced effectively and expeditiously. Judging by the provisions of the New Enforcement Law, the substantial growth in the number of the foreign enforcement applications, and the (limited) positive anecdotal evidence, the author is optimistic that such confidence continues to grow and cases like Jadawel will remain a thing of the past.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.

Many thanks for these information. but i would love to add:

Basically, any foreign award that has been written in another language must be translated into Arabic because it is the language of the country; it must also be translated by a certified translation office that has a licence to do so. this was assured in New York convention where Article IV states a number of formal requirements, namely the supply of a duly authenticated original award or a duly certified copy thereof, an original agreement referred to in Article II or a duly certified copy thereof, and the provision of a certified translation of the foreign award by an official or sworn translator.

This was adapted in several countries, for example, regarding the translation requirement, a recent judgment has been released of White J in the Supreme Court of New South Wales in Yang v S & L Consulting. The application was for a foreign arbitral award made in China under the IAA. The defendants had submitted an English translation of the award, which had been certified by the First Secretary of the Consular Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in China but was not certified by a diplomatic or consular agent in Australia (As required by s10 of the Australian IAA). However, the Court noted that these documents had also been translated by an accredited translator and interpreter in Australia. This translator had identified some mistakes in the certified English translation; none were significant, except a misstatement of the daily percentage rate of interest. The Court also noted that the translation made by the Australian translator was not in dispute and was a translation to the satisfaction of the court within section 9(4) of the IAA. The important point is that the Court recognised that the translation was not disputed by the parties in this case and the court was satisfied with the translation within the meaning of section 9(4) of the IAA (that is, ‘to the satisfaction of the court’).

Unfortunately, there are negative perceptions about Saudi Arabia being a country that discourages enforcement of foreign arbitral awards before the new arbitration law. These negative perceptions are as a result of lack of thorough research; lack of understanding of the Saudi Arabian legal system and laws, lack of translations of Saudi laws and regulations in English for non-Arabic Speakers. Additionally, lack of publically available published decisions which cause misunderstanding, even among many researchers.

So many thanks for this post and please have a look at one of the recent thesis in this regards made by a Saudi Lawyer Aziz Bin Zaid: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/4026/