The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) was signed by its 15 Parties (after India, an initial negotiating party, withdrew from negotiations) on 15 November 2020.1)This article represents the authors’ personal opinions and does not represent the opinion of their respective organisations. The signature of this agreement amid the COVID-19 pandemic has made quite a headline given it is the largest free trade agreement in history in terms of the Parties’ combined GDP. This post analyses the dispute settlement mechanism (DSM) offered under Chapter 10 of RCEP (the RCEP Investment Chapter).

RCEP: Innovations in Investment Protection?

RCEP contains 20 chapters regulating a range of matters, including trade, investment and competition. One of us earlier suggested that the RCEP Investment Chapter could be an opportunity to consolidate and modernize the investment liberalization, promotion, facilitation, and protection regimes applicable to the RCEP Parties, many of which already had international investment agreements (IIAs) among themselves.2)Junianto James Losari, “An international investment agreement for East Asia: issues, recent developments and refinements” in L. Y. Ing, M. Richardson and S. Urata (eds), East Asian Integration: Goods, Services and Investment (Routledge, 2019). For example, the ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement (ACIA), the ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand Free Trade Agreement (AANZFTA), the ASEAN-China Investment Agreement, the ASEAN-Korea Investment Agreement, and the China, Japan and Korea Investment Agreement. However, the RCEP Investment Chapter does not appear to offer advanced refinements to the standards contained in the Parties’ existing IIAs so much as a compromise based on the lowest common denominators amongst the Parties – a topic that goes beyond the scope of this post.

Unlike most of the existing IIAs among Parties, the RCEP Investment Chapter does not contain an investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism. Article 10.18 of RCEP provides a strong indication that the Parties were unable to reach agreement about ISDS. It provides, instead, that the parties would discuss this topic within two years after the date of entry into force of RCEP. The RCEP further removes the capacity for investors to attempt to access ISDS in other investment agreements through the RCEP’s most-favoured nation (MFN) clause: Article 10.4(3) carves out the applicability of the clause to international dispute settlement procedures or mechanisms. Nevertheless, investors may arguably access any more favourable treatment that RCEP may offer by virtue of the MFN clauses (subject to the limitations in those clauses) in their other investment agreements.

This, nonetheless, does not mean that investors are left without any recourse for breaches of RCEP Investment Chapter by a host state. Although the RCEP Investment Chapter does not specify any DSM, an all-purpose state-to-state DSM is provided under Chapter 19 (Dispute Settlement) (the RCEP DSM). This means that if a Party to RCEP commits any breach of the obligations under the RCEP Investment Chapter, the relevant investors could request their home state to espouse their claims by way of diplomatic protection, and subsequently the home state may bring a claim against the host state under Article 19.3(1) of RCEP. Article 17.11 of RCEP, however, carves out a major area of protection by providing that the RCEP DSM is not applicable to disputes relating to pre-establishment rights, namely those disputes relating to admission or approval of foreign investment during the screening process applied by the Parties.

The RCEP further provides the state Parties with the option to choose a forum for the settlement of such a dispute from among their other IIAs provided the dispute concerns substantially equivalent rights and obligations under the RCEP and the relevant IIA. For example, suppose that a dispute regarding a breach of investment protection standards under the RCEP Investment Chapter were to arise between Indonesia and South Korea concerning the impact of Korea’s conduct on an Indonesian investor. In such a hypothetical scenario, the Indonesian government, upon espousing the claim, has the option to bring the dispute to either an ad hoc arbitral tribunal under Article 10(2) of the 1994 Indonesia – South Korea bilateral investment treaty (BIT) or the dispute settlement mechanism under the ASEAN-Korea Investment Agreement or to the RCEP DSM.

RCEP’s State-State Dispute Settlement Mechanism – An Overview

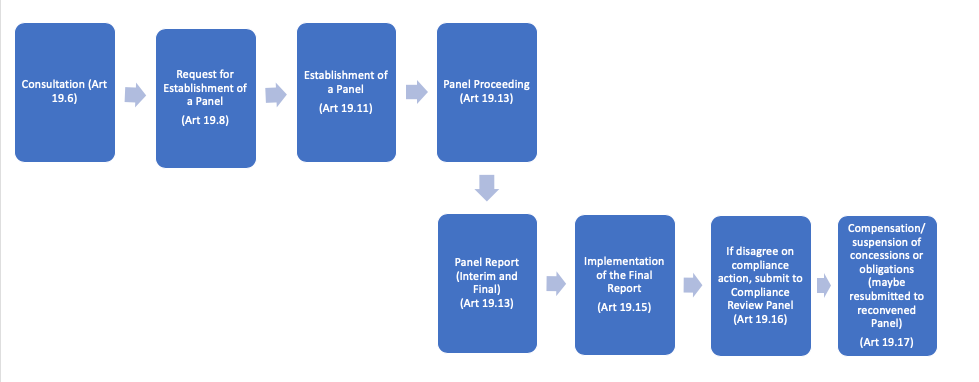

While some aspects of RCEP DSM are similar to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) DSM, some of the main differences in RCEP include the absence of i) a mechanism where panel reports must be adopted by a certain body consisting all parties to the agreement; and ii) an appeal mechanism. We set out below a simplified flow chart summarizing the dispute settlement process under the RCEP DSM. Notably, Article 19.7 of RCEP provides that the Parties to the dispute may at any time agree to take an alternative dispute settlement mechanism, including good offices, conciliation or mediation. In this section, we examine the core features of RCEP DSM, the procedure of which is summarized in the flowchart below.

Flowchart of RCEP DSM (Simplified)

(a) Applicable Law

Article 19.4 of RCEP provides that the RCEP “shall be interpreted in accordance with the customary rules of interpretation of public international law”. It further provides that “findings and determinations of [a] panel cannot add to or diminish the rights and obligations under [the RCEP]”. This is very similar to Article 3.2 of the DSU, which some scholars have regarded as hermetically sealing the WTO from the application of non-WTO treaties or customary international law except for interpretational purposes.3)A Antoni and M Ewing-Chow, “Trade and Investment Convergence and Divergence: Revisiting the North American Sugar War” (2013) 1(1) Latin American Journal of International Trade Law 315. Interestingly, to avoid a paucity of jurisprudence, Article 19.4(2) of RCEP also provides that panels shall also consider relevant interpretations in WTO panels and Appellate Body (AB) reports even for provisions of the WTO Agreement which are not incorporated into RCEP. In relation to RCEP Investment Chapter, Article 17.12 of RCEP incorporates Article XX of the 1994 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), hence various WTO panel and AB reports will be particularly relevant for the interpretation of these General Exceptions.

(b) Panel appointment

Under Article 19.12 of RCEP, an RCEP panel consists of three panelists unless the Parties to the dispute agree otherwise. Similar to the appointment of arbitrators under most major arbitral rules, the Parties to the dispute may each appoint one panelist, and they will jointly agree on the appointment of the third panelist (by providing to each other a list of up to three nominees) who shall be the chair of the panel. If the Parties to the dispute fail to appoint any panelist, RCEP specifies the procedure of appointment, designating the appointing authority as the Director General of the WTO and failing which, the Secretary General of the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

RCEP does not establish a list of panelists for the Parties to choose from. However, Article 19.11(10) and (11) set out the requirements and qualifications that each panelist shall have. Unless agreed otherwise by the Parties, Article 19.11(13) further provides that the chair shall not be a national of any Party to the dispute or a Third Party4)This refers to any RCEP Party who has a substantial interest in the matter besides the disputing Parties as regulated under Article 19.10 of RCEP. and shall not have his or her usual place of residence in any Party to the dispute. While the nationality restriction is similar to that of the WTO DSU5)WTO DSU, Article 8.3 (in which the nationality restriction is more restrictive as it is applicable to all panelists and not just the chair). and some arbitral institution’s rules,6)London Court of International Arbitration Rules (2020), Article 6.1; Singapore International Arbitration Centre Investment Rules (2017), Rule 5.7, though this is only applicable where the Court is appointing a sole arbitrator or a presiding arbitrator; Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre Administered Arbitration Rules (2018), Article 11.2. RCEP adds further requirements that the chair should have served on a WTO panel or the WTO AB and that the chair cannot be a resident in any of the parties to the dispute. This is likely introduced to enhance the perception of impartiality of the panel.

(c) Panel Procedures

Article 19.13 of RCEP sets out some general procedures for the panel proceeding, but also provides more specific procedures under the Rules of Procedures for Panel Proceedings adopted by the RCEP Joint Committee (unless the Parties to the dispute agree to opt for another rules of procedures). At the time of writing, these Rules of Procedures are not yet publicly available. Under Article 18.5(1), the Joint Committee is due to have its first meeting within one year of the date of entry into force of RCEP and so might be expected to produce Rules of Procedures then.

(d) Remedies available to investors

Unlike ISDS which provides a direct remedy to investors affected by a host state’s measure (mostly in the form of monetary compensation), the main remedy under the RCEP DSM is in the form of a final and binding panel report where a wrongdoing state is ordered to bring its measure into conformity with RCEP or carry out its obligations under RCEP. Like in the WTO, if the host state refuses to comply with this order, the home state of the investor may bring a compliance review which eventually can lead to either payment of compensation by the host state to the home state, or where such compensation is not agreed by the disputing Parties, the home state may suspend concessions given to the host state under RCEP. No direct compensation is granted to investors under the RCEP DSM.

Conclusion

The current RCEP DSM may not attract investors of the Parties to use the RCEP Investment Chapter because investors will still need to go through the hurdle of persuading the home state to espouse their claims. Where the claim at stake is relatively small or the investor has limited political capital, there may be less incentive for the home state to bring such a dispute given the political considerations at play. Further, under the RCEP DSM, the investors will likely have much less say in the legal strategy for the dispute. Nonetheless, RCEP does not in any way terminate existing IIAs between the Parties. Those IIAs may still be relied upon by investors.7)RCEP, Article 20.2. This means that investors from relevant RCEP Parties will have the option to obtain protection or to benefit from liberalization commitments under other relevant IIAs with ISDS mechanisms. In conclusion, although RCEP may become the largest trade agreement when it enters into force, it may not be frequently used by investors to resolve investment disputes due to the absence of an ISDS mechanism.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.

References

| ↑1 | This article represents the authors’ personal opinions and does not represent the opinion of their respective organisations. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Junianto James Losari, “An international investment agreement for East Asia: issues, recent developments and refinements” in L. Y. Ing, M. Richardson and S. Urata (eds), East Asian Integration: Goods, Services and Investment (Routledge, 2019). For example, the ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement (ACIA), the ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand Free Trade Agreement (AANZFTA), the ASEAN-China Investment Agreement, the ASEAN-Korea Investment Agreement, and the China, Japan and Korea Investment Agreement. |

| ↑3 | A Antoni and M Ewing-Chow, “Trade and Investment Convergence and Divergence: Revisiting the North American Sugar War” (2013) 1(1) Latin American Journal of International Trade Law 315. |

| ↑4 | This refers to any RCEP Party who has a substantial interest in the matter besides the disputing Parties as regulated under Article 19.10 of RCEP. |

| ↑5 | WTO DSU, Article 8.3 (in which the nationality restriction is more restrictive as it is applicable to all panelists and not just the chair). |

| ↑6 | London Court of International Arbitration Rules (2020), Article 6.1; Singapore International Arbitration Centre Investment Rules (2017), Rule 5.7, though this is only applicable where the Court is appointing a sole arbitrator or a presiding arbitrator; Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre Administered Arbitration Rules (2018), Article 11.2. |

| ↑7 | RCEP, Article 20.2. |

Thanks. I predict that legal advisors will not recommend making foreign investors pursuing indirectly a claim (even if they have political or other clout to mobilise their home state) via RCEP’s sole inter-state mechanism because:

1. As you indicate, many of the 15 RCEP partners “already had international investment agreements (IIAs) among themselves”; in fact almost between each pair (except eg Australia-NZ with a special relationship and even cross-border enforcement of judgments treaty) there are ISDS-backed commitments allowing direct claims against host states – see the Table in:

Nottage, Luke R. and Jetin, Bruno, New Frontiers in Asia-Pacific Trade, Investment and International Business Dispute Resolution (June 25, 2020). in L. Nottage, S. Ali, B. Jetin & N. Teramura (eds), “New Frontiers in Asia-Pacific International Arbitration and Dispute Resolution”, Wolters Kluwer (Forthcoming), Sydney Law School Research Paper No. 20/35, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3635795

2. The inter-state mechanism anyway doesn’t guarantee damages etc for foreign investors; as you observe “if compensation is not agreed by the disputing Parties, the home state may suspend concessions given to the host state under RCEP”.