The Investor-State Dispute Settlement regime is at the centre of a long-standing debate, subsequent reform efforts, and, more in general, great innovation. In this context, on 14 May 2021, a LIDW member-hosted event – organised and co-hosted by Clifford Chance, EFILA, Herbert Smith Freehills, Queen Mary University’s School of International Arbitration, and White & Case – discussed some of the most topical challenges and opportunities in investor-state dispute settlement. Loukas Mistelis moderated the first panel of speakers who focused on the relationship between the European Union and the United Kingdom post-Brexit (see also here on this topic). David Goldberg moderated the second panel of speakers who gave an overview of general trends and developments concerning investment treaties globally. For coverage of earlier sessions of LIDW 2021, please see here and here.

Session 1: The EU-UK relationship post Brexit

The Trade and Cooperation Agreement

In the first session, Jessica Gladstone considered the legal nature of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), concluded between the European Union and the United Kingdom. She commented that the TCA is unique and, as with all Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), reflects a unique balancing of the parties’ objectives, flexibilities, and sensitivities at a particular point in time). Indeed, as she mentioned, there is no ‘single FTA’ model. States’ approaches on certain issues (including Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) – and the very concept of ‘trade issue’ – are constantly evolving. This is clear, for example, if one considers areas now at the heart of modern trade negotiations that would never have been regarded as core ‘trade issues’ in the Uruguay Round of WTO negotiations, such as digital trade, privacy, and to some extent, investment protection. Further, she pointed out that while the TCA does not diverge radically from other trade agreements in terms of structure and style, it has some unique features, such as in-depth provisions on broader issues of law enforcement and judicial cooperation, and more extensive level playing field commitments than are typically included in FTAs, including on environmental protection. Concerning the absence of ISDS provisions in the TCA, she commented that this is not surprising for many different reasons. Amongst others, she mentioned, for example, the European Union’s insistence that an investment court system should deal with investment protection matters, and the practical issue of timing, given the delays and risks associated with domestic constitutional ratification processes. As to the investment protection standards included in the TCA, she noted that these tend to focus on market access rather than traditional investment protection standards.

UK-EU Bilateral Investment Treaties.

Crina Baltag then evaluated the fate of bilateral investment treaties (BITs) concluded between the United Kingdom and Member States of the European Union (UK-EU BITs). In doing so, she pointed out that there is no reference to them in the TCA, although it contains references to other bilateral instruments. For example, amongst others, she referred to Article FINPROV.2 – on the relationship between the TCA with other agreements – which provides that:

this Agreement and any supplementing agreement apply without prejudice to any earlier bilateral agreement between the United Kingdom of the one part and the Union and the European Atomic Energy Community of the other part. The Parties reaffirm their obligations to implement any such Agreement.

Furthermore, she touched upon the topic of termination of intra-EU BITs, and in particular, she made reference to the October 2020 infringement proceedings started by the European Commission against the UK, where the former stated that

without a satisfactory response from the United Kingdom within the next two months, the Commission may decide to refer the case to the Court of Justice of the European Union.

Commenting further on this point, she considered whether the TCA is the “satisfactory response” that the European Commission requested. Finally, she reflected on whether – provided that they are still applicable – we could consider the UK-EU BITs as extra-EU BITs. Finally, she touched upon the future of the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT). Indeed, while it has not been affected by Achmea judgment, modernisation process has started. Further, one must also keep an eye on Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) further developments on this matter, with a view of the Advocate General opinions in Republic of Moldova v Komstroy and Joined Cases C‑798/18 and C‑799/1 (but not developed further in the Judgment of 15 April 2021). In this regard, she noted that it is likely that companies in the energy field may look to structure their investments through the United Kingdom to get access to the European Union.

The TCA and Sustainable Development

Nikos Lavranos pointed out that the TCA contains a specific sustainable development chapter, covering labour and the environment, including specific provisions concerning climate change; and how to reach the targets established by the Paris Agreement. Indeed, the TCA reaffirms the EU/UK’s joint ambition to achieve economy-wide climate neutrality by 2050. In his view, this agreement is arguably the first FTA providing such a specific connection between trade, investment and environmental/climate aspects. However, he noted that in terms of dispute settlement provisions, the TCA might create some problems. For instance, it contains three different types of enforcement and dispute settlement tools and bodies. This proliferation increases the risk of fragmentation and potentially conflicting outcomes. In addition, not giving private parties – businesses and NGOs – the right to challenge a party’s non-compliance with their obligations is unfortunate. Finally, he also reflected on whether the TCA is the appropriate tool to enforce environmental/climate protection goals.

UK’s investment framework

Andrew Cannon considered more closely the UK’s investment framework and noted that the UK is party to a large number of BITs, together with its participation in the ECT. For this reason, the UK represents a favourable location for companies making outward investments. Also, he commented on the UK Supreme Court decision in Micula from early 2020. In this decision, the UK Supreme Court found that the duty of sincere cooperation under EU law did not preclude enforcement of an ICSID Convention (Convention) award against Romania. He noted that the UK, now being outside the EU, has free rein to develop and shape its own investment policy. The precise position it will adopt in this regard was not yet clear. In the 2019 HoC Trade Committee Report, Parliament raised questions of the Government in this regard, stating that the UK cannot go back to its pre-2009 position, and the Government’s response was that it continued to consider a wide range of options. He noted that insight could be gained from recent treaty negotiations. For example, on 4 March 2021, the UK and Singapore published a joint statement reaffirming their agreement to commence negotiations on “updated, high standard and ambitious investment protection commitments”. The UK is also continuing to pursue accession to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (the “CPTPP”), having made a formal application in February 2021.

Session 2: Developments on Investment Treaties Globally.

Criticisms to ISDS

In the second session, Epaminontas Triantafilou gave a broad overview of current issues in ISDS. He started by pointing out that many of the current criticisms of the system (transparency, excessive financial exposure of States) have been around for over 15 years. While those criticisms initially were being raised by academics and non-profit organisations, in time, they came to be reflected in the political will of several States, giving rise to ongoing reform efforts. Current criticisms include the consistency and coherence of arbitral decisions, the process for selecting arbitrators, transparency, and the regulation of third-party funding. He concluded that some of the criticisms have foundation, as well as practicable solutions, and therefore justify efforts at reform. It is important to recall in addressing any problems that the system overall has operated fairly well for decades, injecting the rule of law in an area previously governed by relative diplomatic influence or military might; and has been yielding fairly balanced outcomes. Reform, which is and should remain founded on deliberation and careful cost-benefit analysis, ultimately should be aimed at improvement, not cancellation.

Corporate Social Responsibility and ISDS

Hannah Ambrose discussed how States have addressed Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and environmental protection in investment treaties. In particular, she referred to State-State obligations, through which States generally only acknowledge the importance of CSR and commit to “encourage” CSR compliance. Further, she referred to provisions providing investor obligations on CSR or environment which either constitute “best efforts” or mandatory obligations. She acknowledged that such provisions are likely only to have a practical impact on investor conduct if they are enforceable, and she pointed out that even if treaties were to provide States with the possibility of bringing counterclaims or include a denial of benefits clause where CSR obligations are not met, such provisions would still require an investor to bring a claim first. In this context, she explored whether a solution might be for national courts of the host or home State to have jurisdiction to decide whether investors are in breach of treaty obligations. She concluded that there is opportunity to advance issues of CSR through the framework of investment treaties, but this requires the treaty to prompt a proactive change in investor behaviour. In her view, this requires States to address effective enforcement of CSR obligations in a manner independent of investor claims.

Personal Scope of Investment Treaties

Laura Halonen gave an overview of general trends on the personal scope of investment treaties. Generally, treaties provide nationals of the contracting States – either physical persons or juridical ones – with protection against the State where they invest (Host State). As she mentioned, through investment treaties a Host State aims at promoting investment from the other contracting party by offering it protection in their territory. However, this is not always the case. In some instances, nationals do find a way of effectively being protected against their own State. It is so in case of investors with dual nationality and round-tripping – according to which a national incorporates a company outside their own State to obtain protection under an investment treaty. Investment planning also does not meet the aim of promoting investment genuinely from the other contracting State. In discussing these instances, she gave an overview of how States address these issues in their treaties. For example, she referred to treaty provisions, expressly preventing dual nationals or companies controlled by nationals to bring claims. Another solution is through the denial of benefits clauses, whereby a Host State reserves the right to deny protection to companies owned by their own nationals.

Legality Requirements

Finally, Audley Sheppard examined the requirement of legality of investments under Host States’ law and reflected on whether this is an issue that goes to jurisdiction or admissibility or merits. Among others, he considered whether – absent any provisions prescribing such requirement – an arbitral tribunal can imply this requisite into investment treaties. For instance, he pointed out that this question is relevant when States include it in some treaties while deciding not to do so in other treaties – a question that the Tribunal in Cortec v. Kenya answered in the affirmative. Further, he considered whether such a requirement should be considered a jurisdictional requirement under Article 25 of the ICSID Convention as discussed in Phoenix v. the Czech Republic. In his view, absent an express provision in the relevant treaties, local law compliance should be considered as an admissibility and merits issue (together with State responsibility if public officials are implicated in any wrongdoing), save in situations of serious illegality going to the very existence of an investment. Where there is an express local legal legality requirement, he commended the proportionate analysis in Kim v Uzbekistan.

Final remarks:

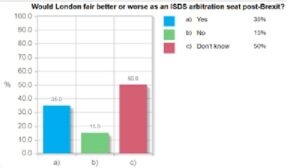

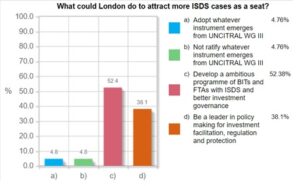

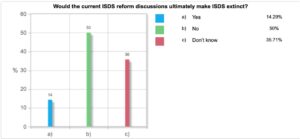

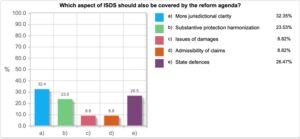

In both sessions, the discussion ended with several questions posed to the audience. The results of the polls to be reflected upon are below:

The author would like to thank Georgios Fasfalis and Maria José Alarcon, assistant editors of Kluwer Arbitration Blog.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.

Congratulations Laura Halonen and entire Wagner arbitration counsel.