On December 2018, the Prague Rules on the Efficient Conduct of Proceedings in International Arbitration (“Prague Rules”) were released. (For related posts on the Prague Rules on Kluwer Arbitration Blog click here, here, here, and here.)

The Prague Rules aim to increase efficiency and reduce costs in arbitral proceedings. The project arose from a general dissatisfaction with both the costs of arbitration and the length of proceedings. Drafters believe that one of the causes of this is that, generally, tribunals are not sufficiently proactive in providing cost efficient and time-saving procedures.

The drafters proposed the Prague Rules as an alternative to the well-known and commonly adopted IBA Rules on the Taking of Evidence in International Arbitration (“IBA Rules”). The note following provides an analysis of the main differences (and similarities) between the IBA Rules and the Prague Rules.

Application

The Prague Rules are intended as a framework providing guidance to conduct effective arbitration proceedings. They do not replace institutional rules which govern arbitral procedure and are only applicable upon the parties’ agreement or at the arbitral tribunal’s own initiative after consultation with the parties and, even then, only to the extent to which the parties have agreed (see Prague Rules, Article 1). In practice, although unlikely, a tribunal could apply the Prague Rules without party consent under Article 1.2.

The IBA Rules, on the other hand, provide that they may be adopted in whole or in part by the parties and tribunals. There is no specific provision for the tribunal adopting the IBA Rules of its own initiative.

Key differences

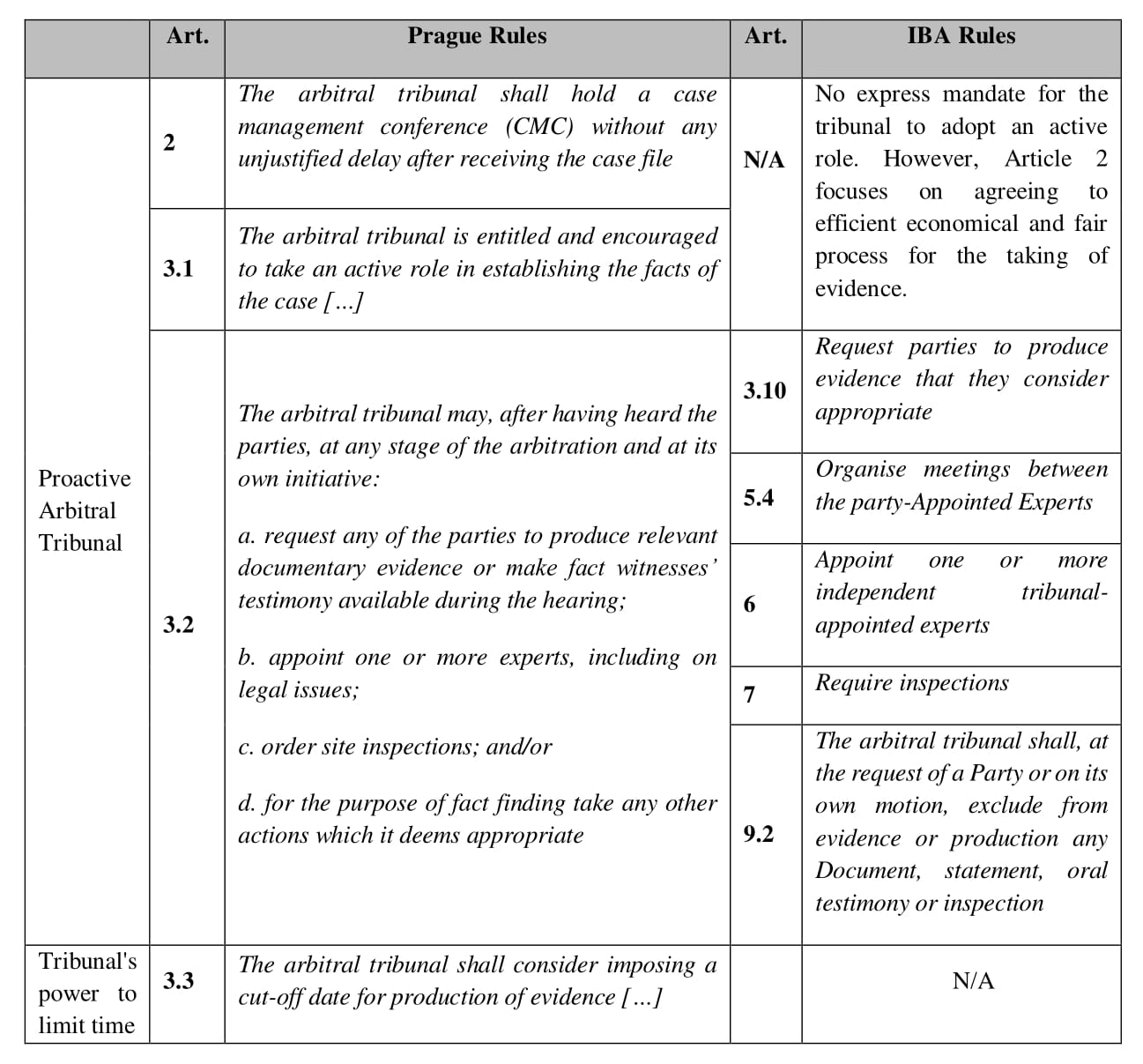

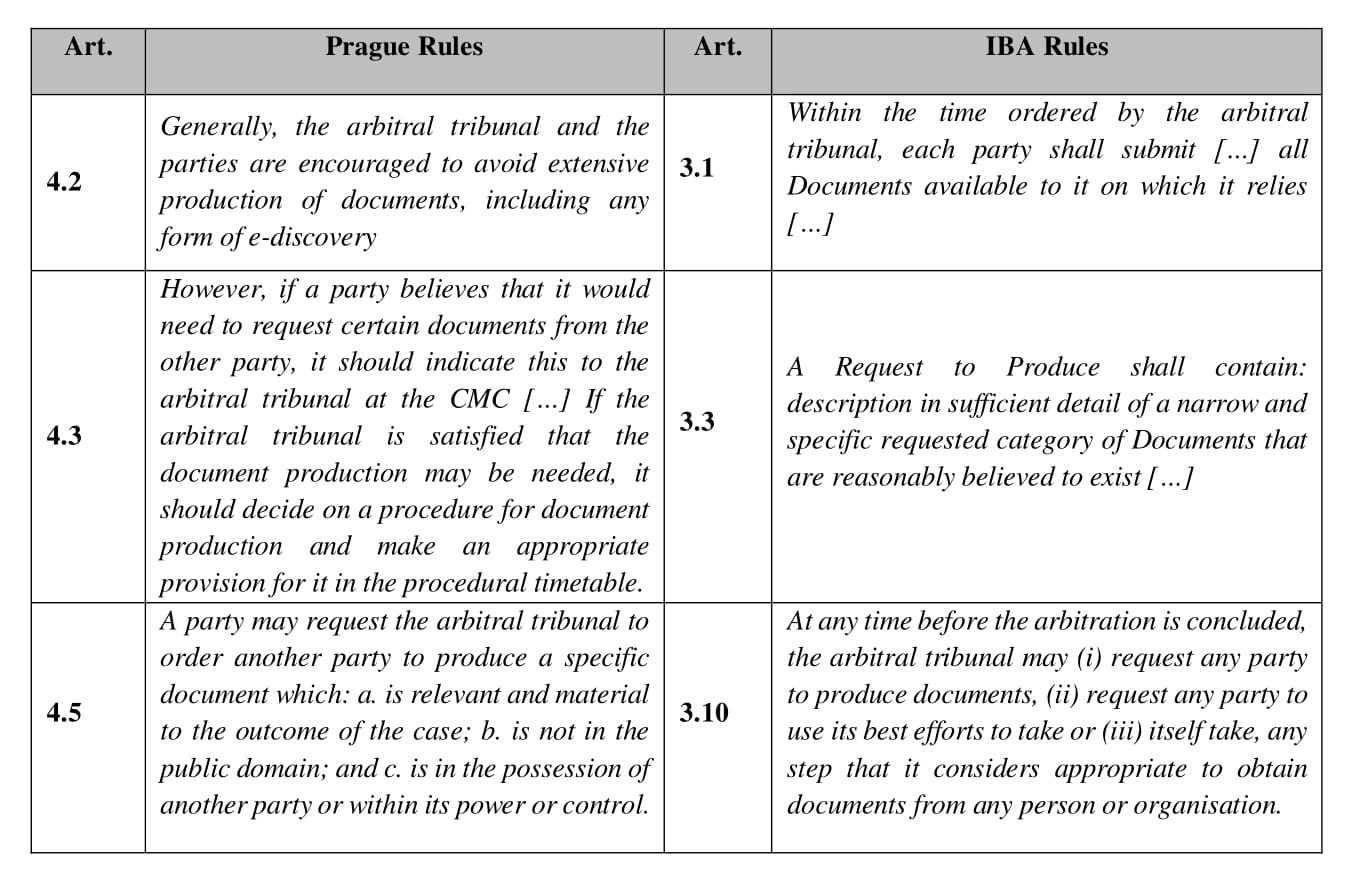

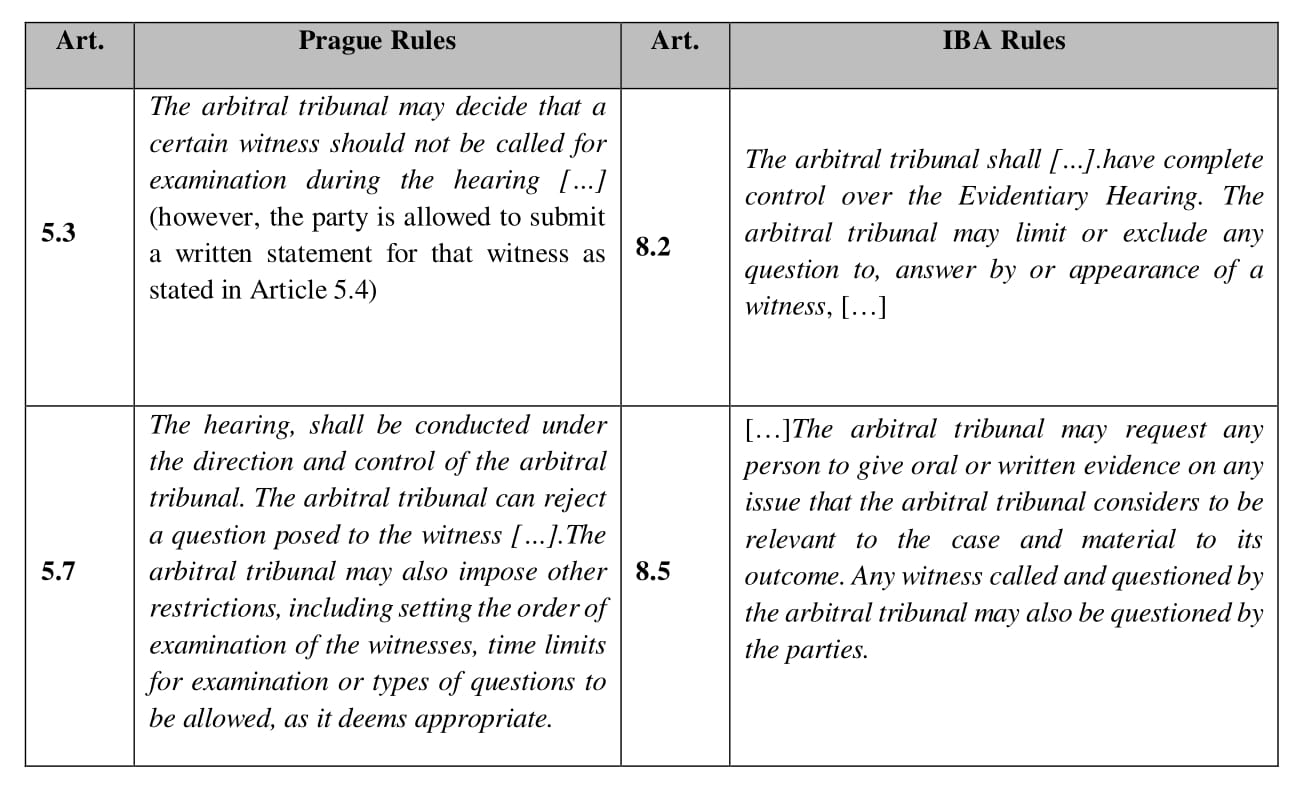

The key underlying difference between the IBA Rules and the Prague Rules is that while the IBA Rules were intended to create a level playing field in international arbitration, it is commonly believed that they are more aligned with common law. In contrast, the Prague Rules openly adopt a more inquisitorial approach more in line with the civil law tradition. This below illustrates, by way of comparative charts, the four main issues addressed by the Prague Rules:

1. A Proactive Arbitral Tribunal: Arbitrators should be active both in the taking of evidence and in fact finding to speed up proceedings.

In sum, the Prague Rules contain unequivocal provisions on how the tribunal should be active. Yet, the IBA Rules also encourage the tribunal to adopt a proactive attitude.

2. Document production: The drafters of the Prague Rules criticise the current IBA-style practice of document discovery arguing that it is highly time and cost consuming. The Prague Rules, following the civil law style, limit document production.

3. Number of witnesses: Another proposed solution to reduce the duration of arbitral proceedings under the Prague Rules is that the tribunal will have the final say regarding the number of witnesses to be heard throughout the proceedings. While under the IBA Rules, the tribunal has no say over this matter.

4. Examinations of witnesses: Despite the criticism of the cross-examination of witnesses in arbitration, the drafters of the Prague Rules retained the cross-examination process in the new Rules. However, provisions that tend to avoid lengthy hearings were included. The Prague Rules even suggest not having a hearing, and when possible, resolving the dispute on a document basis only (Article 8.1).

Innovations

The Prague Rules included two other provisions that are not addressed in the IBA Rules and may not be familiar to common law practitioners:

-

- ‘Iura Novit Curia’ principle (Article 7). This maxim demands for proactive arbitrators who are able to spot and determine the applicable law on their own initiative and thus apply provisions that were not set out by the parties. This requires prior consultation with the parties; furthermore, the tribunal must seek the parties’ views on those legal provisions it intends to apply.

- Assistance in Amicable Settlement (Article 9). Unless the parties object the tribunal may assist the parties in reaching an amicable settlement. This alternative dispute resolution mechanism can be used at any stage of the proceedings. Where that no agreement is reached, the arbitrator who acted as mediator may (a) continue as an arbitrator (parties’ written consent is required) or (b) terminate his/her mandate.

Even though common law practitioners may not be familiar with this mechanism, it is interesting to note that it is used in other jurisdictions, specifically Asia. Similar provisions are contained in the HKIAC Rules 2018 (Article 13.8) and in the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (Article 47).

Conclusion

On the whole, even when there are some differences in procedures under the two sets of rules, the Prague Rules do not present a radical change. However, these changes and innovations could have an impact on the costs and the duration of the proceedings.

Will the Prague Rules yield better results overall? We will have to wait for the Prague Rules to be put into practice in order to fully analyse their impact on international arbitration.

This post is an expression of the author´s personal opinion, the views expressed here do not reflect Clyde & Co’s position.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.

Thank you, Sol, for this excellent summary comparison of the Prague and IBA rules. Some of the new Prague rules implicate the right of the parties to be heard, which may create grounds for challenge at the enforcement stage, and tribunals are well advised to keep that issue in mind while seeking to manage the proceeding efficiently.