The relevance of intellectual property in business is on the rise, in particular concerning cross-border transactions. Accordingly, the willingness to defend such rights is also becoming stronger.

Disputes concerning intellectual property rights are traditionally mainly dealt with before national courts. Yet, in recent years there has been a considerable shift towards arbitration. The acknowledgement that national courts are not always the appropriate forum for IP disputes is driven by the fact that comprehensive technical knowledge is required to decide those cases. Paired with the ever more common multi-state components of such disputes, companies increasingly prefer disputes to be resolved by arbitral tribunals in lieu of state courts.

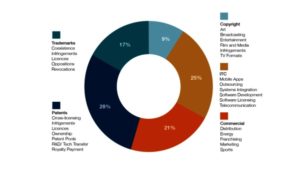

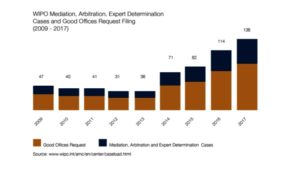

To meet the particular needs in IP and technology disputes, the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) established the WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center (WIPO-Center) and specific arbitration (expedited and non-expedited), mediation and expert determination regimes. Key figures published by the WIPO Center show widespread use of its services in the fields of TMT and IP (WIPO Mediation, Arbitration and Expert Determination Cases) and the number of cases handled by the WIPO Center is consistently growing, showing rising demand for such specialized services:

In a nutshell, the key aspects of the WIPO arbitration regime are:

- WIPO Neutrals: the WIPO Center administers a comprehensive list of experts specialised in various fields acting as arbitrators;

- Specific rules on interim injunctions: quick suspension of infringements is often key in IP disputes – thus, the WIPO arbitration regime provides specific focus on interim decisions;

- Confidentiality regime: IP and technology arbitration often involves secret know-how and trade secrets; the WIPO Rules provide for a specific set of provisions dealing with confidential information introduced in arbitration proceedings;

- Evidence proceedings: the WIPO Rules provide specific sets of provisions on taking evidence via expert witnesses, including arranging for experiments to be conducted during arbitration.

But: IP disputes and arbitration – how do these fit together? When talking about IP arbitration, two main issues must be considered:

- Is an arbitration clause in place? A core element of many IP disputes is the IP owner’s right to prevent others from using its IP (cease and desist claim). As a matter of fact, usually there is no contract in place between the rival parties. And even if there is (for instance licence agreements, technology agreements, trademark co-existence agreements or even transaction agreements also containing IP-related issues), such agreements often do not contain IP-specific arbitration clauses or any arbitration clauses at all.

- Is the matter of the dispute arbitrable? In IP disputes, the existence, validity, ownership or scope of certain IP rights are at least preliminary questions to be resolved before the merits of a case can be determined. With regard to registered IP (such as patents, utility models, trademarks or designs), the question of whether such IP right has been lawfully registered by the authorities is typically resolved in front of the national courts and authorities, and not by private arbitrators.

This can lead to a situation where company A, which owns patent registrations in several countries, is faced with a competitor, company B, which is marketing potentially infringing products in several markets. A and B become involved in patent infringement litigation before several national courts in order for A to prevent the sale of the competitor’s product and in the end to obtain appropriate damages. This may lead to inconsistent national decisions as to (i) the validity of the very same patent in different countries, (ii) whether or not the competitor product infringes the patent, and (iii) the calculation of damages in each market.

Concerning the arbitrability of disputes about the validity of registered IP rights, as long as the preliminary question could also be subject to a settlement between the parties, it is commonly held that this question should be arbitrable.

Here we come full circle: the possibility to arbitrate IP disputes is shown by the ever-increasing number of IP cases solved by WIPO arbitrations. Nevertheless, the question of whether IP disputes are arbitrable in principle recurs time and again. This is historical owed to the assumption that IP rights are of public policy interest. These days it is beyond dispute that the vast majority of cases are arbitrable – at least when it comes to an international context.

This also has to do with the fact that the objection of a lack of arbitrability is not raised as often as assumed in the academic discussion. The reasons for the rather rare objection of non-arbitrability are as follows (see T. Cook and A. Garcia, International Intellectual Property Arbitration, 2010, p. 52/53):

- Most IP disputes brought as arbitrations revolve around contractual problems. Contractual disputes, however, are regularly regarded as being arbitrable in most countries, even if they are related to intellectual property rights (the validity and scope of which may be a preliminary question also in contractual disputes).

- The area of IP disputes that invites the objection of lack of arbitrability is further limited by the fact that only certain categories of IP rights are prone to be excluded from the scope of arbitrations. These rights are, as mentioned above, all those that revolve around the (in)validity and (in)existence of a registered IP right.

- The last limitation of the problem-prone area is that the parties often do not contest the validity of the underlying IP right because they cannot or do not want to. This happens quite often because many IP arbitrations are based on licensing agreements. Yet relatively often these have “non-contest” or “non-challenge” clauses which prevent the validity of the IP right from being attacked. If the validity of IP rights is not in itself a question of arbitration, arbitrability related problems are prevented from arising.

It becomes clear: if certain criteria are met, disputes over IP rights may very well be decided by arbitral tribunals. Of course, the result of such arbitration cannot cause any third-party effect and cannot bind national register authorities to carry out any specific acts as to the registration of the IP rights that were subject to arbitration. But an arbitrator may well decide with inter partes effect whether a patent can be enforced against the defendant or not. However, due to uncertainties in this respect, it is important to check whether such circumstances may render an arbitration award unenforceable under certain national laws.

When drafting arbitration clauses in IP contracts, oftentimes the question arises whether claims for injunctive relief (or preliminary injunctions) should also be subject to arbitration or whether such should be decided on by ordinary courts. However, a limited arbitration clause applying arbitration to any dispute arising under or related to a specific agreement, but excluding actions for specific performance, such as injunctive relief (which particularly in IP disputes usually is a key claim), could turn out to be tricky in practice. In a recent decision in Henry Schein, Inc., et al. v. Archer & White Sales, Inc., 586 U.S. (2019), the Supreme Court of the United States held that the preliminary question as to whether such excluded claims brought by the claimant in front of the ordinary courts itself would have to be determined by arbitration. This leads to a situation (at least in the US) where firstly, it may have to be determined in arbitration proceedings whether a particular claim (e.g. for injunctive relief) is to be heard in arbitration or in front of the ordinary courts, and secondly, such claims may then need to be pursued in front of the ordinary courts (or maintained in arbitration, as the case may be).

When drafting IP and technology agreements or even when being confronted with a (multijurisdictional) dispute scenario, parties should consider specialised IP arbitration as a valid alternative to court litigation. Nevertheless, careful thought must be given to whether this option indeed is fit for the intended purpose.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.