On 1 May 2020, ICSID and UNCITRAL released the long-awaited Draft Code of Conduct for Adjudicators in Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) (“Draft Code”) as previously reported and discussed. Article 1.1 of the Draft Code provides that it applies to “all persons serving as adjudicators in ISDS proceedings”, defined broadly to include arbitrators, ad hoc committee members and judges of standing bodies or mechanisms. This post addresses the potential ban on “double‑hatting” in Article 6, and its impact on gender and regional diversity, as well as the potential barrier to entry of the second generation of arbitrators. The specific draft provision is detailed below.

Article 6. Limit on Multiple Roles

Adjudicators shall [refrain from acting]/[disclose that they act] as counsel, expert witness, judge, agent or in any other relevant role at the same time as they are [within X years of] acting on matters that involve the same parties, [the same facts] [and/ or] [the same treaty].

Comment 66 of the Code of Conduct defines double-hatting as “the practice by which one individual acts simultaneously as an international arbitrator and as a counsel in separate ISDS proceedings.” The comment further states that for some, any concurrent representation creates a conflict of interest and therefore should be prohibited. For others, double-hatting is “problematic only in circumstances, where the facts or parties are related.” Moreover, Comment 67 states that “[a]n outright ban is easier to implement, by simply prohibiting any participation by an individual falling within the scope of prohibition.”

At a glance, it may appear that the potential ban applies to specific scenarios, namely “same facts” and/or “same treaty”. Upon closer examination, however, the provision could potentially be broadly construed to significantly reduce the pool of arbitrators from ISDS cases. For example, “same facts” could be potentially interpreted to cover pandemics such as COVID-19, global financial crises, or natural disasters that impact more than one country. The provision does not specify the year and also includes “agent or any relevant role”. This means that an arbitrator could be excluded for minor advisory work, such as corporate advice on structuring investment and the scope of protection under certain treaty that is unrelated to the dispute.

The Potential Ban on Multiple Roles Could Reinforce the Dominance of the “Male, Pale and Stale” Club

Thoughtful observers are concerned that appointments to ISDS predominantly go to a small club of elite “Grand Old Men”. Indeed, the question “Who are the arbitrators?” was discussed at the 2014 ICCA Miami Conference. Attendees were told that the answer was that they were “male, pale, and stale” – implying that most international arbitrators were senior white men.

It is well acknowledged that diversity is essential to better decision-making as diverse perspectives, knowledge, background and experiences brought by individual talents, male and female, from different regions provide benefits to all. Diversity in ISDS is particularly important because investor-State disputes usually involve significant issues of public policy and public interest. The makeup of decision makers, both in terms of gender and demography, therefore, should reflect the makeup of those who will be affected by such decisions.

Therefore, any sort of blanket ban on double-hatting would have the unwelcome effect of reinforcing the existing dominance of a relative handful of established male arbitrators mostly from Western Europe and North America in the field of ISDS.

- Impact on Gender Diversity

In a prior study of 249 known investment treaty cases up to May 2010, only 6.5% of the arbitrators were women. A survey by the author of 353 registered ICSID cases from 2012-2019 reveals that out of 1,055 appointments, only 152 appointments were of women – just 14.4 %. More striking, of all individuals appointed across all cases, only 35 were female and only two female arbitrators together comprise 45.3% of all appointments of women. Thus, the underrepresentation of women in investment arbitration remains a dire problem.

In investment arbitration, however, individual arbitrators would be drawn primarily from the ranks of counsel who must continue to practice unless and until they receive sufficient appointments to make full-time service as arbitrators economically feasible. Indeed, out of the 427 appointed arbitrators listed by ICSID, 46 are women. Out of these 46 women, 32 have an available curriculum vitae on the ICSID website which reveals that 21 women (or at least 45.6%) currently serve as counsel or as partner in law firms. According to the 2019 ICSID Annual Report, 31% of female appointments were first-time appointees, most likely individuals still serving as counsel. As many female ICSID arbitrators are practicing full-time as counsel, prohibiting double hatting would undoubtedly reduce the already small number of female arbitrators in the ISDS field.

- Impact on Regional Diversity

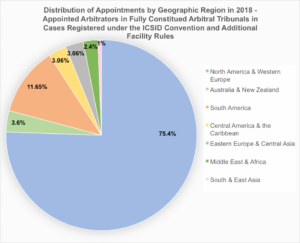

While the total arbitrators appointed represent eighty-eight different nationalities, nearly half of these appointments come from seven nations: New Zealand, Australia, Canada, Switzerland, France, the United Kingdom and the United States. For appointments made in 2018, the percentage of ICSID arbitrators from Western Europe and North America totaled 75.4% while the percentage reached 79% when including Australia and New Zealand.

Due to the lack of geographic diversity, parties are limited when it comes to selecting arbitrators from similar backgrounds. The proposed ban therefore unwittingly serves as a restriction on party autonomy when it comes to appointing arbitrators who understand the parties’ legal, cultural, and socio-political background, adversely affecting the goal of reaching decisions that take those understanding and context into account. The arbitration community should make efforts to broaden regional diversity with the goal of ultimately increasing the fairness and quality of the award, and the legitimacy of ISDS.

- Barrier to Entry for Second Generation of Arbitrators

Generation renewal in arbitration is significant to the arbitration community given that senior arbitrators will inevitably retire. The next generation of arbitrators tend to be practicing counsel and would not be able to give up their counsel professional duties unless and until they receive enough appointments to allow them to serve as full-time arbitrators. Thus, the ban would exclude a greater number of candidates than necessary and pose a barrier to entry by preventing the renewal of the arbitrator pool. This is echoed by Comment 68 to the Code, which states: “A ban on double-hatting also constrains new entrants to the field, as few counsels are financially able to leave their counsel work upon receiving their first adjudicator nomination.” Allowing newcomers to sit alongside more senior arbitrators would enable them to gain more experience and benefit the transition of the next generation of arbitrators.

Equating Arbitrators with International Judges?

The Code should also exercise caution when equating arbitrators with permanent judges for the purposes of double hatting, as the two roles substantially differ. Permanent judges, such as those in the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) International Investment Court (ICS) or the proposed multilateral investment court (MIC), hold tenured office with two-tiered permanent courts, and are assigned to cases on a random and rotational basis without the parties’ input. And they are remunerated on a regular basis. On the other hand, ad hoc arbitrators are appointed by the parties for a specific case and are remunerated on a case-by-case basis, each subject to its own conflict of interest determination. Such distinctive elements are usually what differentiate between international judicial settlement and arbitral settlement.1) See C. Ranjan Amerasinghe, Jurisdiction of International Tribunals, The Hague, Kluwer Law International 2003, pp. 19-20 (Noting that the existence of a permanent structure with tenured pre-selected judges hearing cases on a rotation basis – as opposed to party appointed ad hoc arbitrators – with an institution and secretariat are usually considered as elements that differentiate judicial settlement from arbitral settlement of international disputes.). To illustrate the difference, the EU describes the MIC as bringing features of “domestic and international courts” with selection of judges similar to the International Court of Justice and remuneration comparable to judges in international courts.2)European Commission, ‘Impact Assessment Multilateral Reform of Investment Dispute Resolution’, SWD (2017) 302 final, 13 September 2019, p. 40. The CETA and the International Court of Justice prohibit multiple roles given that the judges serve on a permanent basis and perform roles more akin to judicial public functions.3)See Article 17, Statute of the International Court of Justice, 1945. On the other hand, arbitrators perform more private functions and their conflicts of interest are assessed on a case-by-case basis. Indeed, Todd Weiler has argued that “individuals acting as arbitrators are professionals offering a private service – not officials performing a public service – and that there should be no bright-line prohibition against individuals practicing as arbitrators and counsel contemporaneously.”4) The same query on treating arbitrators as permanent judges should also be scrutinized with respect to the proposed limit on the number of ISDS cases in the controversial Article 8.2 as to how such restrictions could be applied to permanent judges. The number of judges is slated to be fixed and a standing court cannot predict ex ante how many cases will be on the court docket at a given time. Moreover, there has been no allegation, that the existing rules and institutions are unable to manage conflict issues,5)See Republic of Ghana v. Telekom Malaysia Berhad, District Court of The Hague, Challenge No. 13/2004, 18 October 2004; Vito G. Gallo v. Canada, NAFTA/UNCITRAL, Decision on the Challenge to Mr. J. Christopher Thomas, QC, 14 October 2009. nor is there sufficient justification for such radical departure from a time-honored practice when less drastic measures are available to mitigate any conflict issues.

Conclusion

Barring individuals who serve as counsel in ISDS proceedings from serving as arbitrators in investment disputes would reduce the overall pool of potential arbitrators, notably women and those from other regions, and deprive the parties of the ability to select the arbitrators of their choice. Moreover, if the arbitrator pool is not sufficiently appealing, it may attract less-qualified candidates, as the best talents may opt for the more lucrative role as counsel. Therefore, any outright ban of multiple roles simply because it is “easier to implement” should be discouraged. Indeed, Comment 68 should be highlighted, which identifies the barrier to entry as “especially relevant for younger arbitrators (new entrants) and arbitrators who bring gender and regional diversity.” Thus, great care is needed to ensure that the cost of prohibiting double-hatting does not outweigh the impact on diversity. Proposals for a grace period or a “time phased” approach for new arbitrators have been made. However, it would be difficult to implement in practice. Narrowly tailored disclosures, similar to the International Bar Association Guidelines on Conflict of Interest or disclosures,6)It should be noted that Article 5.2(c) of the Code already contains disclosure rules on any role, including that of counsel: “All ISDS [and other [international] arbitration] cases in which the candidate or adjudicator has been or is currently involved as counsel, arbitrator, annulment committee member, expert, [conciliator and mediator]”. See also disclosure in ICSID, ‘Proposals for the Amendment of the ICSID Rules,’ Working Paper #4, Volume 1 Schedule, p. 241. Indeed, the failure to disclose an arbitrator’s relationship to one of the parties’ expert during his previous role as counsel in unrelated cases has recently resulted in the annulment of an award. See Eiser Infrastructure Ltd v Kingdom of Spain, ICSID Case No. ARB/13/36, Decision on the Kingdom of Spain’s Application for Annulment, 11 June 2020. would be more suitable and in line with international practice.

Caution should be exercised when considering measures that would reduce the pool of arbitrators, significantly impact gender and regional diversity, and pose as a barrier to entry for the second generation of arbitrators. It is with full disclosure, that the parties can assess if there is indeed a conflict of interest in a particular case and whether the two parties would accept the individual with knowledge of the potential multiple roles.

Note: The author would like to thank Mr Loic Topalian and Ms Teodora Kovacevic for their assistance in compiling the ICSID statistics on gender and demographic diversity.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.

References

| ↑1 | See C. Ranjan Amerasinghe, Jurisdiction of International Tribunals, The Hague, Kluwer Law International 2003, pp. 19-20 (Noting that the existence of a permanent structure with tenured pre-selected judges hearing cases on a rotation basis – as opposed to party appointed ad hoc arbitrators – with an institution and secretariat are usually considered as elements that differentiate judicial settlement from arbitral settlement of international disputes.). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | European Commission, ‘Impact Assessment Multilateral Reform of Investment Dispute Resolution’, SWD (2017) 302 final, 13 September 2019, p. 40. |

| ↑3 | See Article 17, Statute of the International Court of Justice, 1945. |

| ↑4 | The same query on treating arbitrators as permanent judges should also be scrutinized with respect to the proposed limit on the number of ISDS cases in the controversial Article 8.2 as to how such restrictions could be applied to permanent judges. The number of judges is slated to be fixed and a standing court cannot predict ex ante how many cases will be on the court docket at a given time. |

| ↑5 | See Republic of Ghana v. Telekom Malaysia Berhad, District Court of The Hague, Challenge No. 13/2004, 18 October 2004; Vito G. Gallo v. Canada, NAFTA/UNCITRAL, Decision on the Challenge to Mr. J. Christopher Thomas, QC, 14 October 2009. |

| ↑6 | It should be noted that Article 5.2(c) of the Code already contains disclosure rules on any role, including that of counsel: “All ISDS [and other [international] arbitration] cases in which the candidate or adjudicator has been or is currently involved as counsel, arbitrator, annulment committee member, expert, [conciliator and mediator]”. See also disclosure in ICSID, ‘Proposals for the Amendment of the ICSID Rules,’ Working Paper #4, Volume 1 Schedule, p. 241. Indeed, the failure to disclose an arbitrator’s relationship to one of the parties’ expert during his previous role as counsel in unrelated cases has recently resulted in the annulment of an award. See Eiser Infrastructure Ltd v Kingdom of Spain, ICSID Case No. ARB/13/36, Decision on the Kingdom of Spain’s Application for Annulment, 11 June 2020. |

Nice to hear from you again, Vanina. Unfortunately I am not so persuaded by your analysis. If more prohibitions or other limitations on double-hatting emerge, we can expect less experienced arbitrators to be appointed more say from among professors, ex-judges and other groups, rather than counsel; while more experienced / established arbitrators give up their counsel work that creates at least a strong appearance of bias / conflict. In many countries, women are more likely to be found in senior positions within academia (some of whom may also have earlier had experience as counsel, like yourself) or even nowadays formerly in the judiciary. This shift may also help promote geographical diversity among arbitrators, which hasn’t improved much say re Asia since examined a decade ago:

Nottage, Luke R. and Weeramantry, Romesh, Investment Arbitration for Japan and Asia: Five Perspectives on Law and Practice. FOREIGN INVESTMENT AND DISPUTE RESOLUTION LAW AND PRACTICE IN ASIA, V. Bath and L. Nottage, eds., Routledge, pp. 25-52, 2011; Sydney Law School Research Paper No. 12/27. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2041686

The general public is also increasingly aware, not just in the EU (hence eg CPTPP), that investment treaty cases increasingly raise important public policy issues that call for a more diverse group of decision-makers that are less linked to (often large) law firm practitioners … with scholars highlighting for example the stark contrast with those deciding conceptually sometimes similar issues say in WTO disputes:

Pauwelyn, Joost, The Rule of Law without the Rule of Lawyers? Why Investment Arbitrators are from Mars, Trade Adjudicators are from Venus (October 1, 2015). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2549050 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2549050

Public concerns will only continue to grow as more cases emerge of “role confusion”, even if a statistically small proportion, as recently eg in Eiser and Energia Solar Luxembourg v. Spain (ICSID annulment).

If we want to save the investment treaty system, I don’t think we can rely just on better disclosures to parties, or even (much of) a time-phased approach. For further analysis of this topic, please see our co-authored AcFI concept paper on arbitrator neutrality (updated for JWIT special issue soon) via https://www.cids.ch/academic-forum-concept-papers and generally eg

Nottage, Luke R. and Ubilava, Ana, Costs, Outcomes and Transparency in ISDS Arbitrations: Evidence for an Investment Treaty Parliamentary Inquiry (August 6, 2018). International Arbitration Law Review, Vol. 21, Issue 4, 2018; Sydney Law School Research Paper No. 18/46. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3227401

Thank you, Vanina, for raising a very interesting question about the potential second and third-order effects of the proposed Code. The statistics you have gathered are also very useful to help us better understand the issues at play.

Very well written and thought-provoking. Thank you for the insightful analysis on the important issue of the underrepresentation in ISDS tribunals and how the ban can severly impact diversity. As the drafters are acknowledging this issue themselves, I hope they will take this serious matter into account when finalizing the Code.