On 7 March 2023, Paul Friedland (Partner, White & Case LLP) delivered the 2023 Proskauer Lecture on International Arbitration at the New York offices of Proskauer Rose LLP. Founded in 2013, the Proskauer Lecture provides an annual public forum to expand the horizons of international arbitration through the contributions of leading thinkers and practitioners. Peter Sherwin (Partner, Proskauer Rose LLP) and Prof. George Bermann (Gellhorn Professor of Law, Columbia Law School) introduced Friedland who delivered the tenth Proskauer Lecture.

At the first in-person event since 2019, Friedland addressed a packed crowd on the intersection of the most significant act of sabotage on U.S. soil and the U.S.-Germany Mixed Claims Commission. The subject matter of Friedland’s inquiry spanned decades but began with a single moment: at 2 AM on July 30, 1916, saboteurs detonated a series of explosives at Black Tom Island, a munitions railway depot on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River near the Statue of Liberty. The explosions leveled the depot and blew out every window from the Bowery to midtown in New York City. The sabotage also set in motion a series of events that led ultimately to one of the longest-running interstate arbitrations in history.

By 1916, Black Tom Island – originally named for its first settler in the 19th-century – had become one of the largest munitions depots in the United States and served as a primary storage site for munitions bound for the Allied Powers in Europe during World War I. While the U.S. remained neutral in the War, its arms sales made its munitions industry a target for covert German operations. But, as Friedland explained, how to deal with the arms flow presented a conundrum to Germany. Germany was eager to stem the flow of munitions to its European adversaries but could not risk provoking the United States into joining the War. Germany therefore tasked a network of undercover agents in America to sabotage America’s flow of munitions to Allied Europe without getting caught. After a series of detonations of ships bearing armaments, the German agents’ attention turned to Black Tom, Friedland explained, which was, on any given day, packed with munitions bound for Europe.

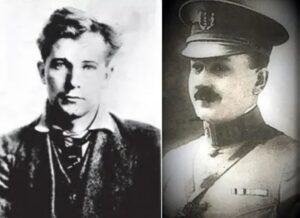

Following the sabotage, the Americans came over time to believe that man responsible was a young and handsome German agent named Lothar Witzke. Shortly before the War broke out, Witzke, originally a merchant marine, traveled from South America to San Francisco and became an agent of the German government. When the U.S. declared war on Germany in 1917, Witzke fled to Mexico with a cohort of German agents. They were joined there by Paul Altendorf – a Polish Jew and double agent named who infiltrated the German cell.

In Mexico, Witzke allegedly confessed to Altendorf that he had been in a rowboat on the Hudson River in the early hours of July 30, 1916, and had detonated the explosions at Black Tom Island. In February 1918, on Witzke’s trip across the U.S.-Mexico border, Altendorf reported Witzke’s whereabouts to the Americans, who quickly arrested Witzke and charged him with espionage. Witzke was convicted and sentenced to death, but his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment by President Woodrow Wilson following the November 11, 1918 Armistice. Witzke’s sentence was eventually commuted and he was sent back to Germany in 1923. Friedland explained that, back in Germany, Witzke became Germany’s star witness in the arbitration that was just getting underway for compensation for the explosions at Black Tom Island.

Witzke denied any role at or knowledge of the sabotage at Black Tom Island. The double agent Altendorf was the Americans’ principal witness. He testified to the Mixed Claims Commission that Witzke had admitted to him that he was directly responsible for the destruction of the munitions depot. As Friedland explained, the way the arbitrators resolved this direct conflict in testimony is one of the ways that the arbitration was unusual.

* * *

In 1930, the Mixed Claims Commission came out with its Decision on the merits of the sabotage claims: a major victory for Germany.

The Commission accepted the Americans case that the various German operatives, particularly Witzke, had admitted during conversations in Mexico to the sabotage at Black Tom Island. Though the Commission accepted that these admissions had been made, this was not dispositive because the Commission found that these admissions were most likely just false boasting.

The Commission made explicit findings of the good faith of the German representatives in its Decision. Friedland posited that the reason that the Commissioners found it appropriate –somewhat unusually – to make a point about Germany’s good faith was that the Americans had relentlessly attacked not just the German witnesses for alleged perjury but also the German lawyers for what the U.S. said was fraud in their submissions.

The Commission also made findings about the two principal witnesses: Altendorf on the American side; and Witzke on the German side. The Commission found that Altendorf was among other things, a “liar” and, indeed, that most of the witnesses in the case were liars.

Friedland explained that this finding was a singularity of the arbitration, and noted that the Commission’s distrust of the witnesses hurt the Americans much more than it did the Germans, because the Americans bore the burden of proof.

* * *

The Americans did not give up after their defeat in 1930. As soon as they could, they filed a petition for rehearing on the basis of proffered new evidence, including new testimony from Germany’s witnesses who now wanted to alter their testimony and a new exhibit: a coded message written in lemon juice in 1917 from one German agent to another.

The Commission rejected the witnesses as liars perhaps suspecting, Friedland suggested, that their testimony had been bought by the Americans. As to the coded message, the Commission agreed it would be dispositive, if authentic. However, the Commission distrusted the witness who purported to have found the coded message, calling him not just a “presumptive [liar,] but [a] proved” liar. The Commission therefore dismissed the American’s petition to reopen – a complete victory for Germany.

Had that been the end of the case, Friedland suggested that the German lawyers might be lauded for “calmly acknowledg[ing] the American case and [offering] plausible counters” in the face of the “hyper-aggressive” American lawyers. The Americans’ aggressive tactics, Friedland noted, “might be legitimate frustration that their rightful claims were being foiled by deception. And another way to characterize the German approach could be that they were effective, but only for a while, at defrauding the Commission.”

In 1933, the Americans filed another petition for rehearing. This petition had some new elements, but it wasn’t so different from the petition that had just been rejected. But this new one was granted, and the case was reopened. Friedland suggested that the reason the new petition was granted despite its similarities to the first petition may have been “that the Americans’ persistence and the steady accumulation of evidence finally got through to the Commission.” But at the same time, the reopening in 1933 coincided with the Nazis rise to power in Germany.

Friedland explained that even after a decade of proceedings, settlement remained unlikely for a variety of political reasons, including disinterest from Nazi command, Germany’s unwillingness to acknowledge a violation of neutrality (even implicitly through settlement), and Hitler’s apathy to the case and general opinion of the United States as socio-economically weakened by the Great Depression.

The proceedings continued for six more years. In 1939, after more briefing, more evidence, and more hearings, the Germans came to believe that the two Americans on the Commission were going to rule against Germany. To try to avoid that outcome, the Berlin government ordered the German Commissioner to withdraw. The German Commissioner did so, alleging that the Umpire, then Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts, was biased.

In June 1939, the American Commissioner – not the Umpire – issued an Opinion that detailed what he found to be fraud in Germany’s earlier submissions. The core of the Opinion was a detailed review of the context, provenance and content of the lemon juice message. The American Commissioner found it authentic. And it followed from this that Germany’s witnesses had been lying for years about their responsibility for the destruction of Black Tom Island. The American Umpire, Justice Roberts, agreed with the American Commissioner‘s Opinion. He set aside the Commission’s prior Decision in favor of Germany and issued an award in favor of the sabotage claimants, finding that the Commission had been “seriously misled” by the entirety of Germany’s submissions.

Friedland explained that it is rare to see an international tribunal in an interstate arbitration finding that one of the States made fraudulent submissions on the core issue in the case.

* * *

Friedland concluded with a query: was the arbitration a success? While the Commission arguably arrived at the correct result, any higher purpose of interstate arbitration was unlikely served by such an acrimonious process, including accusations of perjury, bias, witness tampering, and fraudulent submissions. As for Witzke, Friedland explained that the case was little more than a footnote in his life, which included decades of international intrigue, espionage, brief stints in a British Denazification camp and the Hamburg parliament, with a final demise in the bed of a Stasi agent.

The Proskauer Lecture is a result of a partnership among Proskauer Rose LLP, Columbia Law School’s Center for International Commercial and Investment Arbitration Law, the ICC International Court of Arbitration (delegates Marek Krasula and Paul Di Pietro attended the 2023 Lecture), and the United States Council for International Business (delegate Nancy Thevenin attended the 2023 Lecture).

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.