I first discovered the resemblance between the concepts involved in blockchain arbitration and John Rawls’ ‘veil of ignorance’ while conducting research on the metaverse and arbitration. With the recent enforcement of a blockchain arbitration award by a Mexican Court, it is appropriate to take a step back and analyze the relevance of Rawls’ 1971 theory to modern concepts such as the blockchain, and how it can contribute to the achievement of justice.

The Veil of Ignorance

Rawls was an American political philosopher who, in his seminal work A Theory of Justice, introduced the concept of the veil of ignorance. According to Rawls’ theory, the fairest way to distribute resources in society would be if the allocation was made by individuals who did not know their own future position in society. These people would be positioned behind what Rawls called the veil of ignorance. They would be stripped of their identities, their race, religion, beliefs, customs, abilities, etc., and would be truly ‘ignorant’ of their circumstances, as they would be placed in the ‘original position’. They would not know how the various alternatives before them would affect themselves, and they would have to make choices only based on general considerations. They would know the principles of economic and social theory, general laws, human psychology, and the basis of social organizations. These people, as per Rawls, would be the best arbiters of social decisions.

Rawls argues that the decisions of such persons behind the veil of ignorance would be based on two principles: the ‘equal liberty’ principle, which gives each person the right to as much freedom as is compatible with the freedom of others; and the ‘difference’ principle, which allocates resources so that the benefit of the least advantaged people is maximized as far as possible. It is important to note here that both of these approaches to decision-making are based on the generally immutable tenet of ‘justice as fairness’ conceptualized by Rawls. ‘Fairness’, as envisioned by Rawls, is not anchored to the strict application of the law and legal provisions but has a flavor of moral normativity and use of the law in an unbiased manner. While many lawyers might disagree with such an understanding of fairness, Rawls opined that justice cannot be achieved by using the law to step on the underprivileged.

The Working of Blockchain Arbitration: The Case of Kleros

In brief, blockchain arbitration refers to dispute settlement by a crowdsourced, decentralized, and anonymous decisionmaker (jury) that is economically incentivized (using game theory principles and cryptocurrency rewards) to reach a consensus and issue a decision. Kleros is one such platform that makes use of two cryptocurrencies: its in-house Pinakion (PNK) and Ethereum (ETH). Initially, users of the Kleros platforms are to use fiat money, such as the Indian rupee, to purchase ETH and then use ETH to purchase PNK. The ETH is also used to pay the ‘gas fee’, which is like the transaction fee for the use of the ETH blockchain. The disputants submitting a dispute to Kleros must first deposit an arbitration fee in PNK, which is distributed to the jurors on the basis of their outcome.

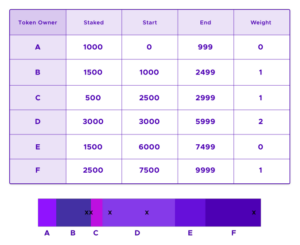

Arbitrators in Kleros are called ‘jurors’. Every juror must first stake a certain amount of PNK at a Kleros court as an entry fee. Kleros uses the proof of stake system, which means the more PNK a juror stakes, the higher the likelihood of them being selected as a juror. The probability of being drawn as a juror is proportional to the number of staked tokens. An illustration of the proof of stake is illustrated below (source: Kleros Short Paper).

The jurors, once selected, are to decide the dispute based on the description of the dispute, the applicable laws, and the digital evidence submitted by the parties. The entire process takes place on the blockchain, where the input (evidence) is used for the production of an output (an award). After each juror decides on an award, they are classified as either a coherent juror or an incoherent juror. A coherent juror is one whose decision is that of the majority, whereas an incoherent juror is one whose decision contradicts the majority. For example, let us imagine that we have five jurors (A, B, C, D, and E) and two disputants (X and Y). If A, B, and E rule for X, whereas C and D rule for Y, then A, B, and E are coherent jurors while C and D are incoherent jurors.

The jurors are given economic incentives to reach a coherent decision. The arbitration fee deposited by the disputants is divided between the coherent jurors, whereas the incoherent jurors do not receive any remuneration. Moreover, the incoherent jurors lose the PNK they had originally staked in order to be appointed as jurors, whereas the coherent jurors are reimbursed. Thus, the system is modelled on game theory, where the jurors are economically incentivized to reach a coherent conclusion.

Are the Jurors behind the Veil?

The decision-making process employed by Kleros jurors is similar to the operation of the Rawlsian veil of ignorance. The jurors are not related to the disputants in any way. They are merely virtual beings that are part of the blockchain with no expression of a tangible identity. Just like in the Rawlsian veil of ignorance, when persons in the original position do not know the position they would occupy in society and they do not know how their choice would affect them, it is in this position that these persons would make the decisions that are best suited for society. In theory, a juror would try to render a decision that is free from any sort of bias, and they would not be influenced by their predicaments because of the monetary incentive present upon rendering a coherent decision. By doing so, they would be rendering a Rawlsian ‘fair’ decision rather than a mechanical application of the law.

Thus, as the persons behind the veil of ignorance are motivated to make decisions relating to society in a way that is beneficial for the greatest number of people and, consequently, beneficial for themselves, the jurors are motivated to reach a decision that would be similar to a majority of the jurors, all of whom would be similarly incentivized to render a fair and reasoned decision. Both of these groups of people are free from personal biases that may affect their choices and decisions.

Moreover, Kleros is designed to facilitate the rendering of decisions on an ex aequo et bono basis, provided the parties to the dispute are in agreement as to a decision on such basis or there is no restriction on this. Ex aequo et bono can be defined as a manner of deciding a case pending before a tribunal with reference to the principles of morality, fairness, and justice in preference to any principle of positive law. Deciding cases on an ex aequo et bono basis is also permitted under Article 28(3) of the UNCITRAL Model Law, subject to its proviso that the parties have expressly authorized it.

As jurors might not have expertise in the subject matter of the dispute, they can rely on the general principles of fairness and justice to reach a decision that would be sought by the majority of jurors. Even if they do possess the expertise, they may shy away from relying on it to make their decision, as their objective is to reach a majority decision, and not necessarily a legally correct decision. It would be reasonable to assume that a majority decision would be closer to a generally fair decision than to a ‘legally correct’ decision, as the jurors are not usually legal experts but merely persons with the largest PNK stake.

This, again, is similar to how the persons in the original position behind the veil of ignorance make decisions. They do not have any expertise in the equitable organization of society but only possess a general understanding of economic and social theory, and thus it is reasonable to assess that the decisions they would make would also be based on the simple tenets of justice, fairness, and morality—on an ex aequo et bono basis. Here, the two principles provided by Rawls become even more important. While they are not directly employed by Kleros’ jurors, they are ultimately rationales based on the general maxims of fairness and justice.

Conclusion

While there might be ethical and moral challenges in providing economic incentives to achieve a fair outcome, they exist only in theory—especially for blockchain arbitration. The ‘commodification of justice’ poses a problem that is resolved by blockchain arbitration, viz, the risk that bias might creep in for the sake of a ‘fair’ decision. However, as analyzed above, blockchain arbitration minimizes the potential for arbitrary and biased decisions.

Rawls’ theories have been criticized as being too ideal for non-ideal times, but the use of blockchain arbitration might prove to be an effective example of the actual manifestation of his theory. Blockchain arbitration is nothing like the traditional dispute settlement mechanism and has the potential to transform justice delivery. Blockchain arbitration mechanisms show how justice can be delivered in a ‘Rawlsian-fair’ manner. Uncertainty of the outcome, economic incentives, the application of ex aequo et bono decision making, freedom from bias, and the loss of identity are just some ways in which the veil of ignorance and blockchain arbitration can be tied together for a truly decentralized resolution of disputes and delivery of justice.

Further posts in our Arbitration Tech Toolbox series can be found here.

The content of this post is intended for educational and general information. It is not intended for any promotional purposes. Kluwer Arbitration Blog, the Editorial Board, and this post’s author make no representation or warranty of any kind, express or implied, regarding the accuracy or completeness of any information in this post.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.

Congratulations Aryan for such an informative and matured article.. I have found it very helpful to understand the basic concepts

I think that the so called blockchain arbitration award has nothing to do with blockchain arbitration. The Mexican Court dealt with an award made in regular arbitration proceedings in which the sole arbitrator and the parties agreed that the answer to a question shall be obtained from the Kleros protocol, which answer was included in the sole arbitrator’s award. As a result there is no Kleros award, or Kleros award enforcement. Kleros does not equate to arbitration but merely provides a yes or no answer to a very simple question. It does not result in an award.