International arbitration is a constantly evolving field, shaped by global shifts, technological advancements, and changing expectations. On 31 August 2023 and 1 September 2023, the ICAL Alumni Association held the ICAL 20th Anniversary Conference entitled “Evolution or Revolution: Have We Mastered International Arbitration or Do We Need a New Blueprint for the Future?”.

Carolyn Lamm’s (White & Case) keynote address opened the conference and explored the history of international arbitration and its progression to date. This progression stands on the reform efforts of countless institutions and bodies over the years. Using ISDS as an example, Lamm posited that international arbitration continues to adapt and improve to fit the current global system. She also highlighted the importance of preserving key principles such as procedural fairness and due process, whilst also promoting innovation and adjustment, and ensuring every voice is heard. ISDS was an echoed example throughout the panels, the consensus being that evolution is the way forward.

International Arbitration of Tomorrow: Meeting the Demands of an Evolving World

The first panel, moderated by Jim Morrison (Peter & Kim), kicked off with a very stark message. Kabir Duggal (Arnold & Porter) noted that for international arbitration to keep up with the changing world, it had to “develop or die”. He expressed that we must not only be ready to adapt, but this adaption must extend beyond discussions at conferences and must carry through in practice. Potentially tough changes are necessary to ensure that arbitration remains relevant. Ndanga Kamau (Ndanga Kamau Law) and Reza Mohtashami KC (Three Crowns) noted that this requires a collective effort, and change must begin with arbitral organs working together.

Ginta Ahrel (Westerberg & Partners) and Eden Li (WongPartnership LLP) then discussed the legitimacy of arbitration in the wake of attacks on ISDS and what this meant for arbitration in general. Is greater transparency needed for revolution? The panel considered this question against the need to maintain confidentiality and balance competing common and civil law practices. It was established that greater transparency is beneficial in public interest matters but not all matters; we need not revolutionise but rather use the tools already in the toolbox to think outside the box.

Rise of the Machines or Sleep Mode: Is International Arbitration Ready for the Technology Revolution?

The second panel, moderated by Mihaela Apostol (Arbitration Consultant & Co-Founder ArbTech), focused on AI in contemplating the readiness of international arbitration in the current technological revolution. Monica Crespo (Jus Mundi) noted the different AI Models (machine learning, artificial neural networks, and language models) and highlighted how each may be used in arbitration (from e.g., assisting with e-discovery to briefly analysing and drafting). Joel Altschul (EY) then illustrated the various ethical considerations that must be considered when engaging with such technology. He noted that we must be careful to ensure that AI does not, for example, misrepresent or produce false information, or conduct an arbitrator’s reasoning.

Sophie Nappert (3VB) highlighted the inconsistencies between jurisdictions in dealing with AI. Whilst the EU has proposed AI legislation to regulate this area, the UK has taken a vastly different approach and not created anything binding, delegating responsibility to various industry regulators. UK regulators have yet to adopt any such measures, and even if (when) they do, they will not be binding and may be contradictory. Anibal Sabater (Chaffetz Lindsey) observed that the Silicon Valley Arbitration and Mediation Center’s draft guidelines on the use of AI in arbitration is one of the first of its kind and that it addresses a key consensus discussed at the conference, decision making cannot be delegated to AI.

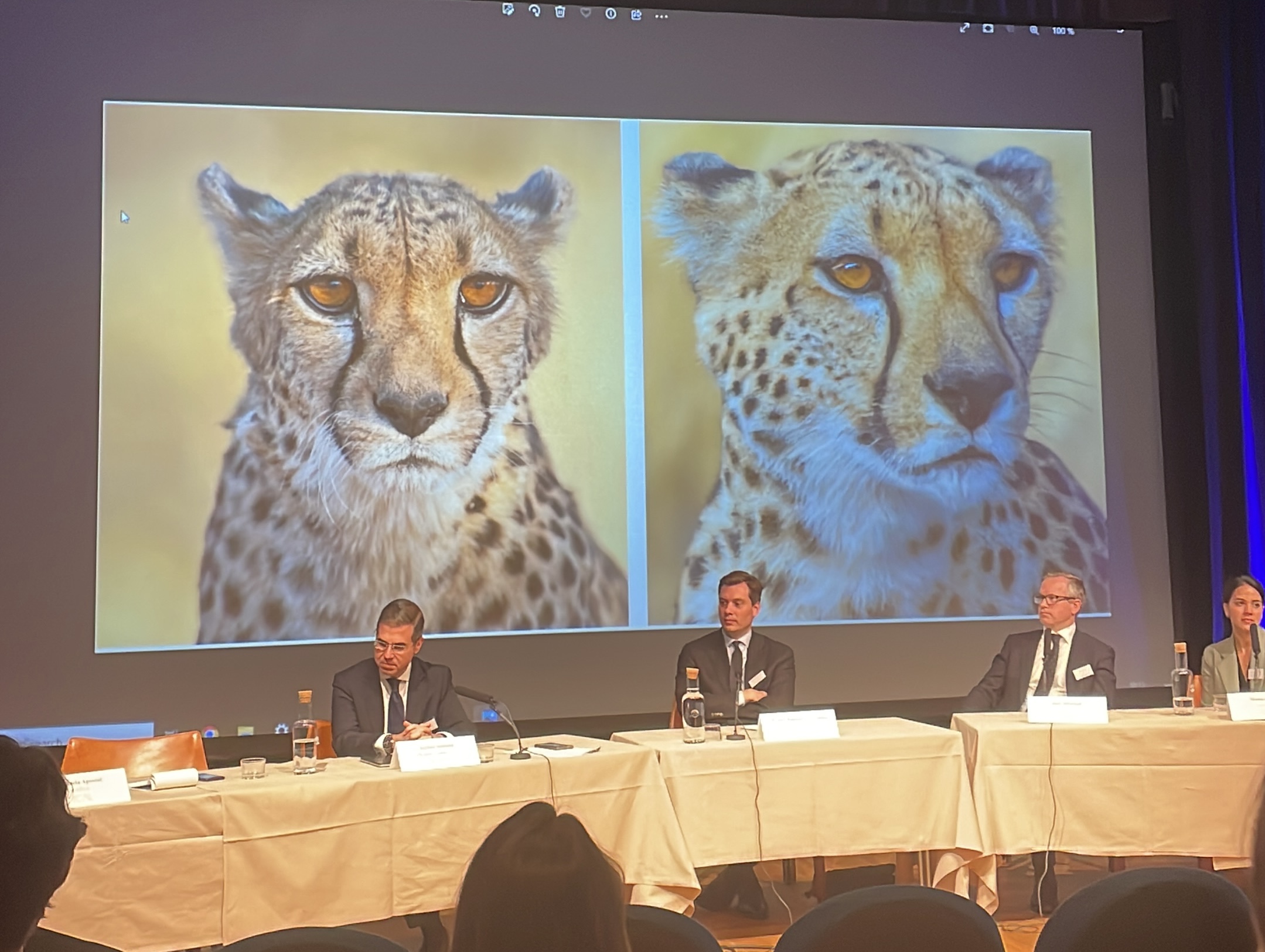

Edward Jansson Stiernblad (Vinge) then posed the question “is seeing still believing?” with respect to deep fake evidence and highlighted the difficulty for tribunals in dealing with contested evidence. Apostol posited that seeing is still believing and used the following image to demonstrate:1)The original cheetah image was taken from National Geographic: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/how-can-you-tell-if-a-photo-is-ai-generated-here-are-some-tips.

Whilst both animals seem to be real at first glance, one can ascertain that the right image is fake due to the eyes, AI cannot yet generate the eyes accurately.

Do Arbitral Institutions Need More Input from Us?

In the third panel, comprised of Caroline Falconer (SCC Arbitration Institute), Luíza Kömel (CAM-CCBC), Kevin Nash (SIAC), Celeste E. Salinas Quero (ICSID) and moderated by Professor Dr. Stefan Kröll (Bucerius Law School) it was agreed, as a starting point, that institutions must cater to the views and preferences of the end users. At the same time, the panel noted certain cases where unworkable agreements may require the institution to exercise discretion and oversight. By way of example, the panel observed that detailed appointment requirements or qualifications, can, for example, make it extremely difficult and sometimes impossible to appoint an arbitrator in accordance with the terms agreed by the parties. The panel agreed that, absent a well-drafted agreement, the better approach may be to suggest qualifications required of the arbitrators and leave the appointment mechanisms to the institution.

The panel also discussed the ongoing debate concerning party autonomy versus institutional oversight. Where should the line be drawn? Is it possible for an institution to override party autonomy? Although there was no strict consensus, circumstances were detailed in which institutions have clarified that party autonomy can sometimes be overridden; this situation may occur where party autonomy conflicts with explicit institutional rules from which the parties cannot derogate. It was also noted that express agreements need to be read through the lens of the agreed institutional rules and, for increased clarity, institutions have responded by updating the language of their rules to increase the use of “shall” and “must” rather than “may”. Also, in the case of ICSID, the ICSID Convention establishes certain limits in terms of nationality and other requirements, that parties cannot modify, such as for arbitrator appointments made by the Chairman of the Administrative Council (Articles 38 and 40(1) of the ICSID Convention) and the constitution of ad-hoc committees (Article 52(3) of the ICSID Convention).

Institutions have evolved to keep up with the expectations of users. The panel evidenced the evolution seen in institutions with respect to the adoption of various express resolution pathways to cater for an evolving market. However, it was noted that institutions must be careful to maintain some individuality so that users have varied options.

Conflicts, Independence, Impartiality: Are the Views on Conflicts Stale?

Conflicts, independence, and impartiality have long been a “hot topic” within the arbitration community given the vital importance these principles have in maintaining arbitration’s legitimacy. Demonstrative of this is the current reform efforts of various international soft law instruments.

Erica Stein (Stein Arbitration) noted that this year the IBA Arbitration Committee constituted a task force to revise the 2014 IBA Guidelines on Conflicts of Interest. She noted that the task force’s proposed revisions (which have been circulated for public consultation this September 2023) are not a revolution but rather an evolution that seeks to reflect best practice in international arbitration. However, Johan Sidklev (Roschier) posited that issue conflicts are not sufficiently regulated and ought to be given the increased demand for disclosure and the difficulty in knowing where to draw the line. With respect to the UNCITRAL and ICSID Code of Conduct for ISDS matters, Professor Loukas Mistelis (Clyde & Co.) posited that it was “low hanging fruit” but questioned whether it has “become sour grapes”. As established previously, Professor Mistelis acknowledged that confidentiality, disclosure, and double hatting are key areas of debate and stated that a ban on double hatting could limit experience, especially in smaller jurisdictions and particularly in investment arbitration, and ultimately, is not what the investors want. It will be for the users to determine whether this Code sets the appropriate standard.

Sara Koleilat-Aranjo (Morgan Lewis) stated that disclosure should not be assimilated with a conflict. She further stated that with the globalisation of arbitration, we should approach disclosure from a global lens and avoid limiting a collapsed regulatory framework to ensure that it remains a flexible and malleable tool used to uphold the credibility and the sanctity of the arbitral process. Koleilat-Aranjo also warned against excessive or over disclosure when Giulio Palermo (Archipel) questioned whether increased transparency will increase disclosure. Sidklev also issued this warning, commenting that you “don’t want to poke a bear that is sleeping” as increased transparency can initiate a response from the parties.

Identifying and Confronting the Challenges of Corruption in Arbitration

As highlighted by Ignacio Torterola (GST LLP), and originally stated in an ICC award, “corruption is an international evil”. This sentiment expresses the importance of this topic, one that captured the lively discussion of the panel, moderated by Jurgita Petkute (KNOETZL).

Maria Kostytska (Winston & Strawn LLP) commenced the discussion by presenting vivid case law examples which highlighted that corruption allegations can play a role at various stages and can present itself in numerous contexts in an arbitration, from being a ground to jurisdictional objection, to denying recognition and enforcement of an award. Kostytska pointed to the added difficulty in a scenario when neither party raises corruption, but it is the “elephant in the room” that the deal does not make sense.

Rikard Wikström-Hermansen (Independent Arbitrator) presented two schools of thought related to the arbitrators’ duties and powers to address corruption sua sponte: (1) the tribunal abstains from raising the question sua sponte and deals with claims anyway as it does not have an inquisitorial role; and (2) the tribunal uses its evidentiary powers and obligations related to public policy to confront it. The panel conceded that the route taken depends on the level of sensed corruption and its potential legal impact; it cannot be vague, but you do not want to and should not act as a “rubber stamp in a money laundering scheme”. This led to questions on the associated standard of proof. Steven Finizio (WilmerHale) suggested that there is a lack of clarity with regard to both the burden and standard of proof. This issue is further complicated by the reliance by both states and investors on indirect evidence of illegal conduct, including arguments based on “red flags”.

Whilst the limits remain uncertain, the panel highlighted that the tribunal always has some power to take a stand, with Kostytska reminding us that the tribunal is never obliged to issue a consent award, it simply may.

Trusted Advisors Outside the Hearing Room

The final panel, moderated by Sherlin Tung (Withersworldwide), provided many valuable insights from an in-house counsel perspective and considered key focus areas when faced with a dispute. Resolution was collectively agreed as a focus; however, Tuuli Timonen (Nokia Technologies) made it clear that there are many other factors to consider when commencing a dispute. A standout being that one must always look beyond the individual case and to the company’s bigger picture. Henri Hätönen (Outokumpu) exclaimed that “winning isn’t always everything”; a win in one case could mean a loss for the company in other disputes. The panellists agreed that external lawyers retained who failed to understand this were not going to last long.

Edgar Martinez (Japan Tobacco International) stated that “the arbitration is as good as the arbitrators.” We can and thus must ensure that international arbitration continues to succeed and remain relevant by working together as a profession to evolve.

Conclusion

John Fellas’ (Fellas Arbitration) day two keynote captures the essential takeaway from the conference: evolution is needed for arbitration to adapt and survive. Fellas stated that international arbitration has shown that it can evolve, demonstrated recently by the best practices that emerged from COVID-19. He posited that we must stay away from rigid blueprints that may “freeze in place practices that made sense once but not going forwards” to ensure that international arbitration maintains its requisite flexibility. We must work together and not get complacent to ensure that we continue to meet current and future challenges. Collectively we can ensure that international arbitration remains a trusted, efficient, and relevant form of global dispute resolution.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.

References

| ↑1 | The original cheetah image was taken from National Geographic: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/how-can-you-tell-if-a-photo-is-ai-generated-here-are-some-tips. |

|---|