International arbitration specialists frequently estimate that national courts give effect to about 90% of all international arbitral awards. Recently, several scholars have set out to empirically test this estimated 90% enforcement rate (see here, here, here, and here). When they ran their numbers regarding how frequently national courts give effect to awards, however, they found courts giving effect to awards at rates significantly lower than 90%. If these studies are correct, one of the most cited reasons to favor international arbitration over litigation—the likelihood of post-award enforcement—might be called into question.

While increased empirical research in international arbitration is a welcome development, we believe that these empirical studies all suffer from some methodological shortcomings that have distorted their results. The primary methodological deficiency of these studies is their reliance on commercial databases, such as Westlaw or kluwerarbitration.com. These databases exist for lawyers to conduct legal research. They collect cases for the purpose of that substantive research. The datasets needed for reliable empirical research, by contrast, are different.

Many cases in which national courts give effect to awards are routine, with little substantive content. Court decisions that are short on substantive legal analysis tend to be of little use for substantive legal research. As a result, databases that are tools for substantive legal research, like Westlaw and kluwerarbitration.com, do not contain (or purport to contain) a comprehensive or representative set of all cases. By contrast, a key requirement of empirical research is that it be based on a reliably representative dataset. For a more reliable measure of judicial treatment of arbitral awards, we used a different dataset to assess the rate at which U.S. federal courts give effect to international arbitral awards. In this blog post, we explain our empirical study of post-award actions in U.S. federal courts that is based on a dataset developed from a review of all federal court dockets. After noting our central findings and comparing our findings with other studies, we provide some practical perspectives on the practice of international commercial arbitration in U.S. federal courts.

I. Our Dataset

We sought to minimize the problems in previous studies by assembling our own original dataset from U.S. federal court dockets, which contain all cases filed in federal courts. Based on our original dataset, we find that other empirical studies understate, sometimes dramatically, the rates at which U.S. federal courts give effect to awards.

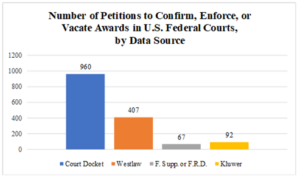

Our original dataset consists of 960 petitions to confirm, enforce, or vacate international arbitral awards that were filed in cases docketed in U.S. federal courts between 2011 and 2019. Our dataset is much more comprehensive than datasets used in previous studies. Of the 960 petitions in our dataset:

- only 67 (or 7.0%) resulted in opinions published in either the Federal Supplement or Federal Rules Decisions (the official reporters of federal district court decisions in the United States);

- only 407 petitions (or 42.4%) resulted in opinions available on Westlaw; and

- only 92 petitions (or 9.6%) resulted in opinions available on kluwerarbitration.com.

The Figure below illustrates the relative comprehensiveness of these data sources compared to our dataset collected from court dockets.

II. Judicial Outcomes in Our Dataset

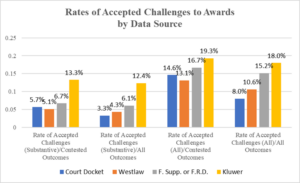

Based on our dataset, we find that U.S. federal courts vacated or denied confirmation or enforcement on substantive grounds at far lower rates than the 10% rate inferred from the famed 90% estimate. In fact, federal courts accepted challenges based on substantive grounds in the Federal Arbitration Act (“FAA”) or New York Convention for only 5.7% of contested petitions and only 3.3% of all petitions. This latter estimate includes the 383 petitions with outcomes that were contested by the losing party and 344 petitions with outcomes that were not contested by the losing party (for a total of 727 petitions), but excludes 127 settled cases, 99 voluntary dismissals, and seven partial confirmations.

When we counted not only petitions dismissed on substantive grounds, but also those that were dismissed on procedural grounds, we found that courts vacated, denied, or dismissed confirmation or enforcement of 14.6% of contested petitions and 8.0% of all petitions.

Both these findings differ substantially from prior studies. The first set of numbers (looking only at when courts accepted substantive grounds under the FAA and New York Convention) are significantly lower than the rate of nonenforcement inferred from the 90% estimate. When challenges based on procedural grounds are included, the numbers are somewhat higher. but still lower than the findings in other studies. We believe these findings provide a more accurate accounting of U.S. federal court treatment of awards than other studies because our dataset is more comprehensive and representative. These differences are reflected in the Figure below.

III. Other Interesting Findings

Using our original dataset, we also examine a variety of other aspects of petitions to confirm, enforce, or vacate international arbitral awards in U.S. federal courts. From this aspect of our work come three other findings of interest.

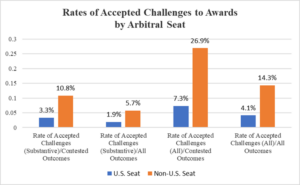

First, U.S. federal courts accepted challenges to awards at much higher rates for awards with non-U.S. seats (10.8% and 26.9%, respectively, for contested petitions and 5.7% and 14.3%, respectively for all petitions) than for awards with U.S. seats (3.3% and 7.3%, respectively, for contested petitions and 1.9% and 4.1%, respectively, for all petitions). These findings are represented in the Figure below.

It should not be assumed that the higher rate of accepted challenges is the result of bias against foreign seats. There are several possible explanations for the higher rate at which courts accepted challenges from non-U.S.-seated cases, which may also provide some practical takeaways.

For example, personal jurisdiction might be more difficult to establish when the arbitration is seated outside the U.S. than when it is seated within the U.S.. For U.S.-seated arbitrations, the agreement to a U.S. seat constitutes consent to personal jurisdiction for the purposes of challenging the award. Parties might have trouble establishing personal jurisdiction in cases involving non-U.S. seated arbitrations that do not benefit from this sort of consent. Additionally, parties might be less likely to have assets in the U.S. if the award is seated outside the U.S. (or vice versa), which might bring stronger (or weaker) petitions to enforce than petitions to confirm.

As a practical takeaway, these findings may suggest that parties contemplating enforcement of foreign awards in the U.S. may want to include consent to personal jurisdiction in the U.S. in their arbitration agreements.

Second, in roughly one-third of all petitions filed in U.S. federal courts, parties did not rely on an applicable international arbitration convention. Parties relied on the New York or Panama Conventions (or implementing legislation) in only 64.2% of petitions that we identified as legally subject to one of the Conventions. The remaining petitions typically relied instead on either Chapter 1 of the FAA, which governs domestic arbitrations (29.6%), or state law (2.8%). This finding is somewhat puzzling and may again point to a practical takeaway.

Although the grounds for challenging awards under the Conventions are nearly identical in substance to those that apply under Chapter 1 of the FAA, see Restatement of the U.S. Law of International Commercial and Investor-State Arbitration § 4.9, rptrs. note a (Am. L. Inst. 2023), there are some potential advantages to seeking enforcement under the Conventions. For example, parties in U.S. federal courts must establish not only personal jurisdiction but also federal subject-matter jurisdiction. Chapter 2 of the FAA, which implements the New York Convention into U.S. law, provides for subject-matter jurisdiction for award enforcement under the Convention (9 U.S.C. § 203). In addition, although rarely ever granted, challenges based on manifest disregard and forum non conveniens are less available under the Conventions. Practitioners (and their clients) need to be aware of these differences when filing post-award actions and should not simply rely on the FAA or state law.

Third, the outcomes of many petitions to confirm awards in U.S. federal courts are uncontested, meaning the losing party either never shows up in court, or appears in court but ultimately does not contest the confirmation of the award. In fact, uncontested petitions outnumber contested petitions. Of the 960 petitions in our dataset, the outcomes in only 390 (40.6%) were contested by the losing party, while 570 (59.4%) were uncontested.

There may be several reasons why winning parties might file petitions to confirm or enforce awards that end up being consented to (or at least not opposed) by the losing party. One reason is to obtain the benefits of a longer statute of limitations. The statute of limitations under the FAA for confirming an international arbitral award is three years, but the statute of limitations for a court judgment confirming that same award can range from five to 10 years. Indeed, even winning parties who anticipate voluntary compliance may want back-up insurance that does not expire in three years.

Another possible explanation is that the losing party’s failure to contest a petition may be the first time a winning party becomes aware of the losing party’s willingness to comply, or at least unwillingness to actively oppose confirmation or enforcement of the award. In this way, a failure to contest a petition may function as a signal that facilitates settlement or other resolution.

Whatever the reason for the high rate of uncontested outcomes, we believe they are an important feature of parties’ post-award conduct. In another forthcoming (2025) article (Compliance in the Shadow of the Award, 50 Yale J. Int’l L.), we explore how uncontested petitions relate to another often-cited but ultimately unsupported statistic in international arbitration: 90% of international arbitral awards are voluntarily complied with.

While our dataset is free from some of the methodological limitations of those in prior studies, our findings are still subject to important limitations. First, our dataset still might not be complete, even if substantially more complete than the datasets used for prior studies. Second, selection bias resulting from the petitions filed by parties might explain some of the differences we found. For example, the higher rates of successful challenges to awards with non-U.S. seats than for awards with U.S. seats might be due to differences in the relative merit of the petitions filed in each category, rather than different treatment by courts in ruling on each category of petition. Finally, our data was limited to U.S. federal courts. Challenges may have different rates of success in U.S. state courts or courts in other countries.

IV. Conclusion

Based on our data, we find that U.S. federal courts are more likely than previously assessed by other empirical studies to give effect to international arbitral awards, sometimes significantly more likely. Our hope is that this empirical research will be helpful to scholars and practitioners and encourage research in other jurisdictions to test the rates at which international arbitral awards are enforced in national courts.

This blog post is based on our article, Challenging and Enforcing International Arbitral Awards in U.S. Federal Courts: An Empirical Study, 65 VA. J. Int’l L. (forthcoming 2024).

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Arbitration Blog, please subscribe here. To submit a proposal for a blog post, please consult our Editorial Guidelines.

It would be interesting to see how other countries fare in similarly sourced data sets and to see whether the apparent bias with regard to non-native seats may be present in such data sets as well.